11 Immigrant Scientists Who Made Great Contributions to America

Coming to America

Throughout America's history, immigrants have played a vital part in shaping the country's growth and progress as a nation. They arrived seeking opportunities that were out of reach in their native lands; in many cases, they were escaping religious or ethnic persecution, or fleeing the horrors of war or natural disasters.

Scientists of all types have numbered among those pursuing a new life in America. In doing so, they brought expertise that significantly contributed to progress in their respective fields, advancing scientific discovery in disciplines ranging from theoretical physics to pathology to biochemistry.

Immigrant scientists have also received some of the highest accolades in science for their pioneering work; since 2000, 40 percent of the Nobel Prizes won by Americans in the areas of chemistry, medicine and physics — 31 of 78 awards — were earned by immigrants, Forbes reported.

Here are 11 scientists who began their scientific journeys in different countries — but eventually, the paths that they followed all converged in America, the country they came to call their home.

John James Audubon: Naturalist and artist (1785–1851)

John James Audubon was born in Saint Domingue (now known as Haiti) and grew up in Nantes, France. He was sent to America in 1803 at the age of 18, to avoid conscription into the French army.

Audubon investigated and documented observations of the natural world, showing a special interest in birds. He identified 25 bird species and 12 new subspecies, but he is perhaps best known for his extraordinarily lifelike drawings and paintings of birds in their natural habitats, drawn with careful attention to anatomical detail. His crowning achievement was the book, "Birds of America," which compiled 435 watercolor prints and is considered a landmark of wildlife illustration.

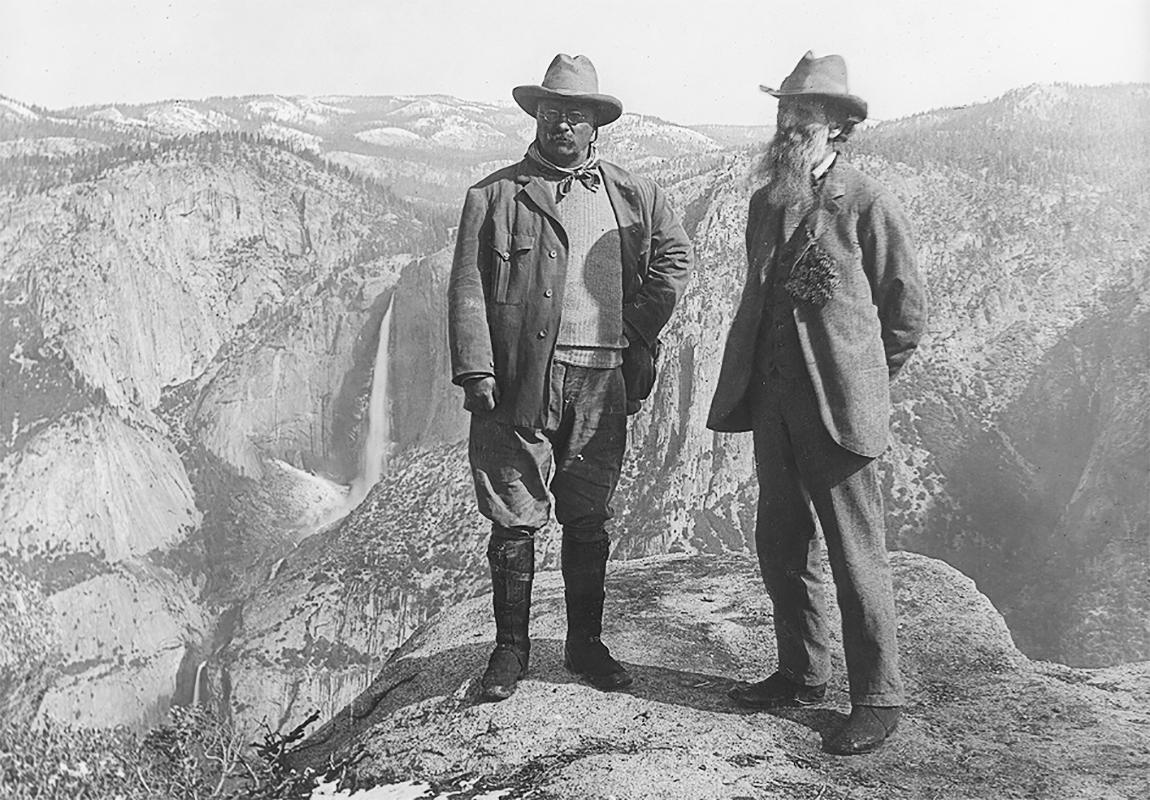

John Muir: Naturalist and writer (1848–1914)

Naturalist and writer John Muir was born in Scotland, emigrating to Wisconsin with his family in 1849. Fascinated by wild spaces from a young age, Muir observed and wrote extensively about the beauty of the natural world. He was especially captivated by the California landscape, particularly Yosemite and the Sierra Nevada mountain range.

Muir published 10 books and 300 articles describing his travels, and promoting an appreciation for nature and conservation. He was instrumental in the creation of several national parks, including Yosemite, Petrified Forest, Mount Rainier and Grand Canyon, and he worked closely with President Theodore Roosevelt to establish conservation programs across the country.

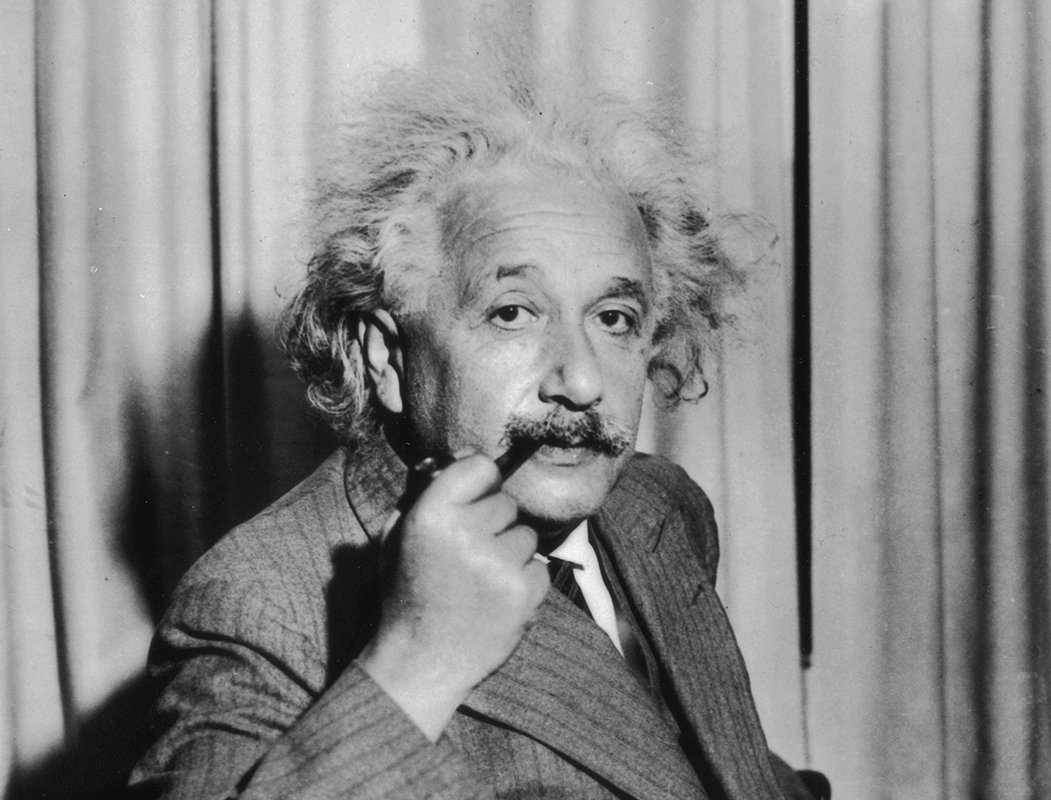

Albert Einstein: Theoretical physicist (1879–1955)

Born in Germany, Albert Einstein followed a more convoluted path than most toward his eventual American citizenship.

Einstein renounced his German citizenship in 1896 at the age of 17, and became a Swiss citizen in 1901. He entered the civil service in Germany in 1914 and regained his German citizenship, only to renounce it and flee the country in 1933, spurred by anti-Semitism and the growing power of the Nazi party. After emigrating to America to accept a position as a professor of theoretical physics at Princeton, Einstein became an American citizen in 1940, maintaining dual citizenship with Switzerland.

Einstein was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1921 for his explanation of the photoelectric effect — how light creates electricity — with the groundbreaking observation that light behaved as a particle as well as a wave. He is also known for developing the theory of special relativity, which describes the relationship between space and time, and the theory of general relativity, defining gravity as linked to the curvature of space and time — the first major theory about gravity since Newton's in 1687.

Gerty Cori: Biochemist (1896–1957)

Born in Prague, Czechoslovakia — now known as the Czech Republic — Gerty Cori (neé Radnitz), received a doctorate in medicine from the German University of Prague in 1920, emigrated to America with her husband Carl Ferdinand Cori in 1922, and became a naturalized citizen in 1928.

Cori was appointed a professor of biochemistry at the Washington University Medical School in St. Louis in 1947. She collaborated with her husband, also a biochemist, in most of her research, and they were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1947 — along with Bernardo Alberto Houssay — for their work decoding a form of glucose, contributing to scientific understanding of the role played by hormones in metabolizing sugars and starches.

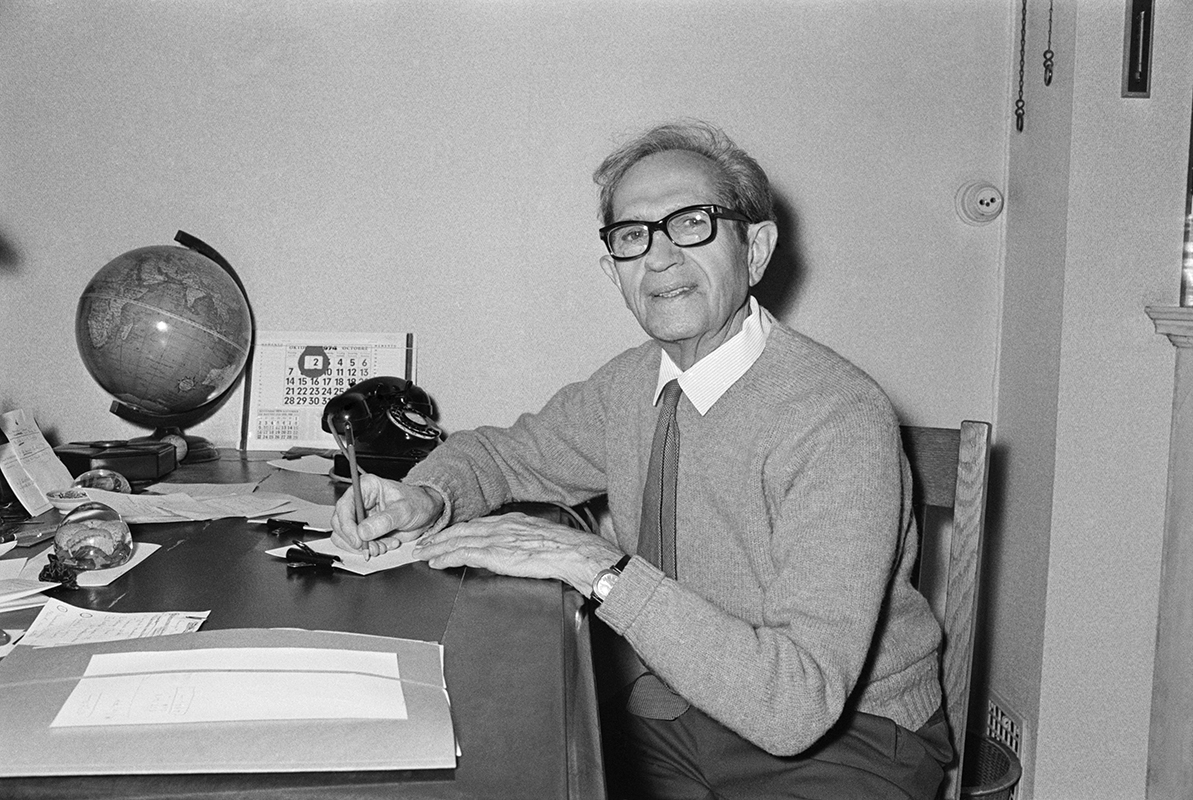

Albert Claude: Cell biologist (1898–1983)

Albert Claude was born in Longlier, Belgium, and obtained a medical degree in 1928 from Belgium's Université de Liège. Claude traveled to New York City that same year to work at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research. He became a U.S. citizen in 1941, arranging for joint citizenship with Belgium in 1949.

Claude launched the field of cell biology by developing a technique that could separate parts of a living cell for examination under high-magnification electron microscopes. He shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1974 for this groundbreaking work, and spent subsequent decades analyzing and mapping cell structures and their functions.

Maria Goeppert Mayer: Theoretical physicist (1906–1972)

Maria Goeppert Mayer (née Maria Goeppert) was born in Kattowitz, Germany (now Katowice, Poland), and attended the University of Göttingen, where she earned a doctoral degree in physics in 1930. She emigrated to the U.S. with her husband that same year, becoming an American citizen in 1933.

Goeppert Mayer worked on the Manhattan Project team, researching the separation of uranium isotopes for the development of nuclear weapons. She later co-developed a novel model explaining how nuclei were distributed in atoms based on their energy levels, and was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963 for this discovery, along with Eugene Wigner and J. Hans D. Jensen.

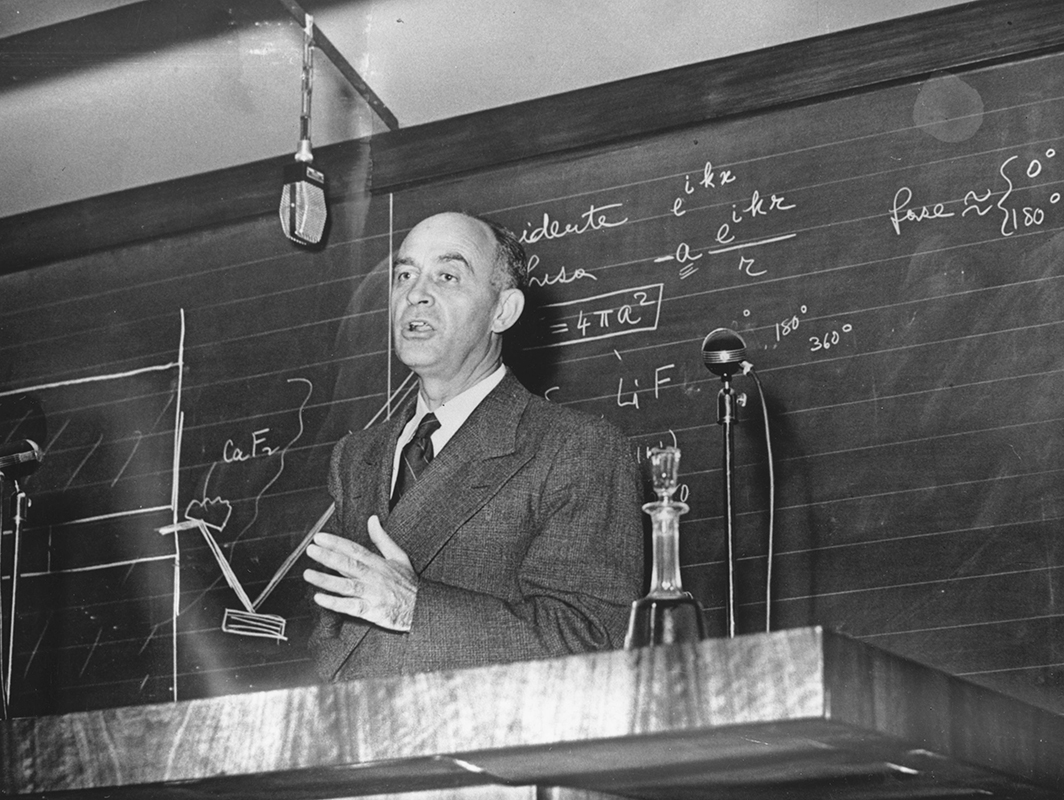

Enrico Fermi: Physicist (1901–1954)

Physicist Enrico Fermi, a prominent scientific figure of the nuclear age, was born in Rome, and received his doctoral degree in physics from the University of Pisa in 1922. Fermi won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1938 for discovering new radioactive elements produced by irradiating neutrons, and he emigrated to the U.S. that same year, fleeing the fascist dictatorship that was emerging in Italy under Benito Mussolini. He became a U.S. citizen in 1944.

Fermi is perhaps best known as the leader of the team of physicists behind the top-secret Manhattan Project, formed by the U.S. government in 1941. Under Fermi's guidance, Manhattan Project scientists produced the first controlled nuclear chain reaction, a breakthrough that led to the production of the world's first nuclear weapons.

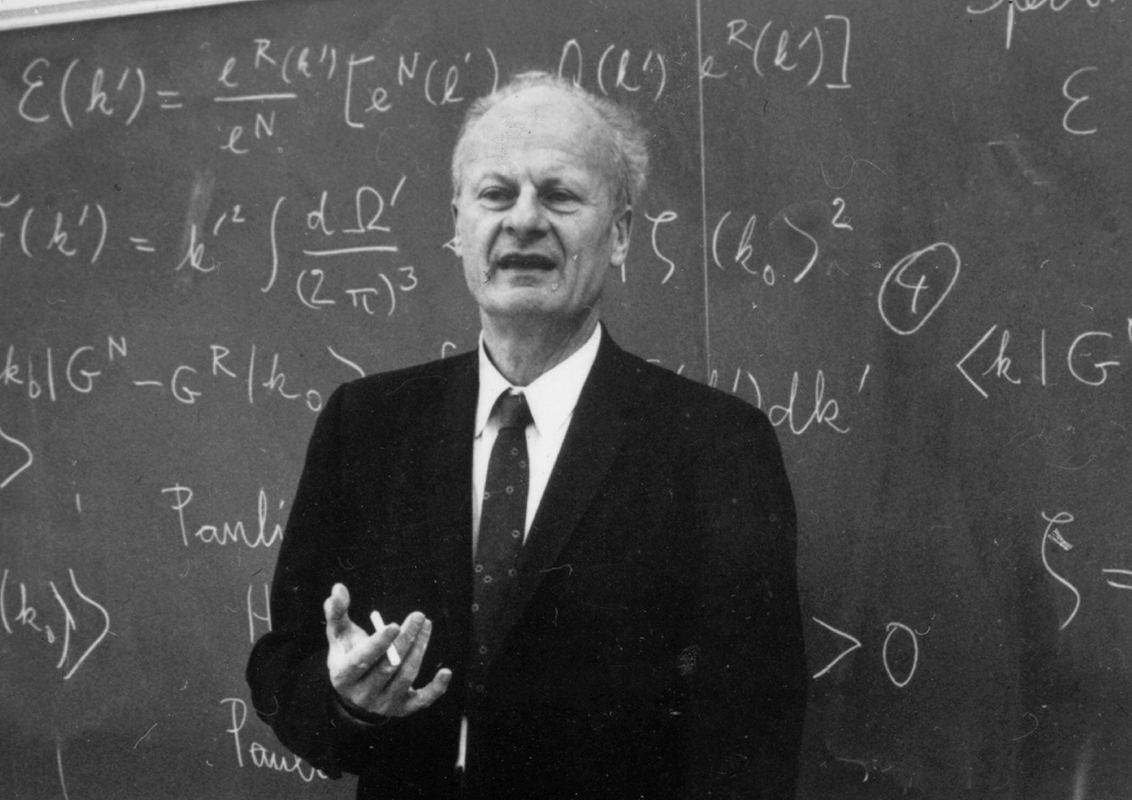

Hans Bethe: Physicist (1906–2005)

Born in Strassburg, Germany (now Strasbourg, France), Hans Bethe studied physics at the University of Frankfurt, earning his doctoral degree in 1928. In 1933, as the Nazi party gained power in Germany, anti-Semitic policies led to his dismissal from his position as assistant professor at the University of Tubingen. Bethe emigrated to the U.S. in 1935, becoming a citizen in 1941.

Bethe's work in the U.S. as part of the teams developing atomic arsenals in the 1940s inspired him to later promote education and public awareness about nuclear weapons and arms control. Over subsequent decades he campaigned to end nuclear testing and encouraged scientists to cease designing new nuclear weapons. In 1967, he received the Nobel Prize in Physics for discovering the reactions that generate energy in stars.

Elizabeth Stern: Pathologist (1915-1980)

Elizabeth Stern, born in Ontario, Canada, attended medical school at the University of Toronto and received her U.S. citizenship in 1943. She became a professor of epidemiology — the medical branch examining patterns of diseases — at the University of California in 1963, and was one of the first researchers to specialize in the study of diseased cells.

Stern published a study describing a link between herpes simplex and cervical cancer; her discovery is thought to be the first case study linking a specific virus to a specific type of cancer. She was the first to link oral contraceptives to cervical cancer, and her work investigating cervical cells identified 250 progressive stages as the cells transitioned from healthy to cancerous, enabling earlier cancer detection and treatment.

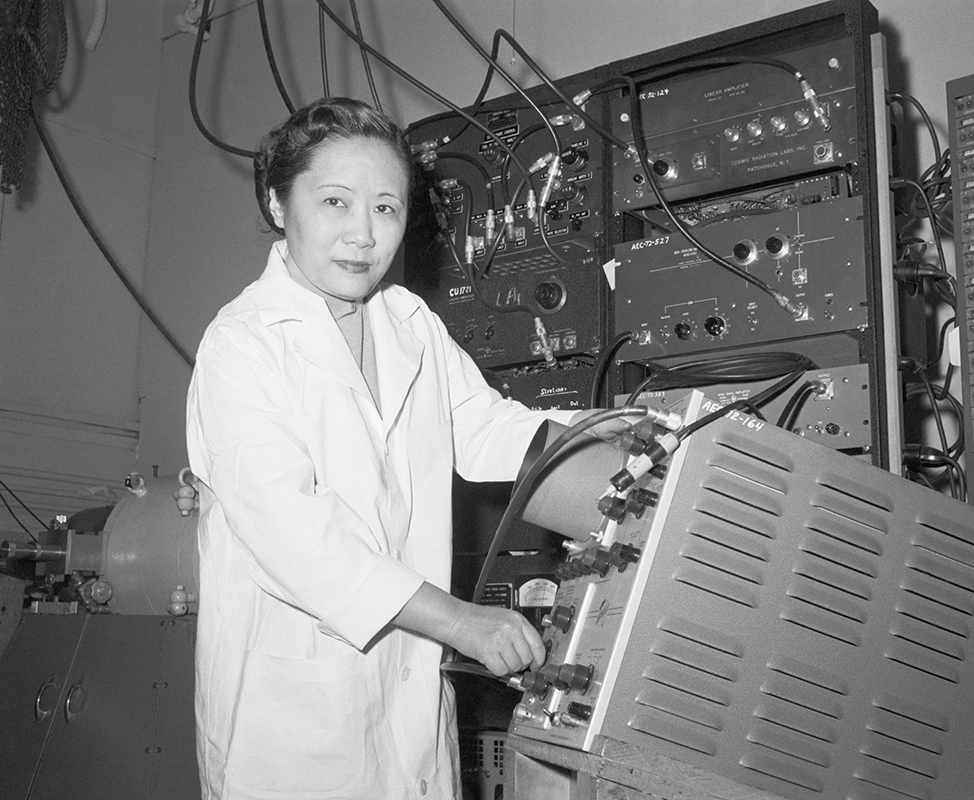

Rita Levi-Montalcini: Neurobiologist (1909–2012)

Rita Levi-Montalcini was born in Turin, Italy, and studied medicine at the University of Turin, graduating in 1936. Through World War II, Levi-Montalcini lived under precarious conditions in Mussolini's Italy; barred from academic work and in hiding due to her Jewish ancestry, she conducted neurological research on chicken embryos in a makeshift lab in her own home.

Levi-Montalcini relocated to St. Louis, Missouri, in 1947 to accept a post at Washington University, and she eventually became a dual citizen of the U.S. and Italy. In 1986, she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with biochemist Stanley Cohen for isolating a protein that contributed to embryonic cell growth, transforming scientific understanding of how cells divide and multiply.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.