Huge Undersea Landslide Slammed Great Barrier Reef 300,000 Years Ago

More than 300,000 years ago, a colossal undersea landslide sent huge amounts of debris sliding down the Great Barrier Reef, generating a 90-foot-high (27 meters) tsunami, researchers have discovered.

Perhaps luckily for creatures in the area, that tsunami wave would have been dampened by the surrounding reefs, the researchers said.

The slide would have sent about 7.6 cubic miles (32 cubic kilometers) of rubble plunging down a slope of the Australian reef. (For comparison, the volume of the Great Pyramid of Giza is about 91 million cubic feet, or less than one-100th of a cubic mile. That means a volume of some 12,000 Great Pyramids plunged to the seafloor during the prehistoric landslide event.)

The culprit of the slide? "We believe an earthquake of sufficiently large magnitude was the most likely trigger for such a landslide event," study researcher Robin Beaman of James Cook University in Queensland, Australia, told Live Science in an email. "As for, 'Would a similar phenomenon happen today?' the continental slope sediments appear stable under current conditions." [Infographic: Tallest Mountain to Deepest Ocean Trench]

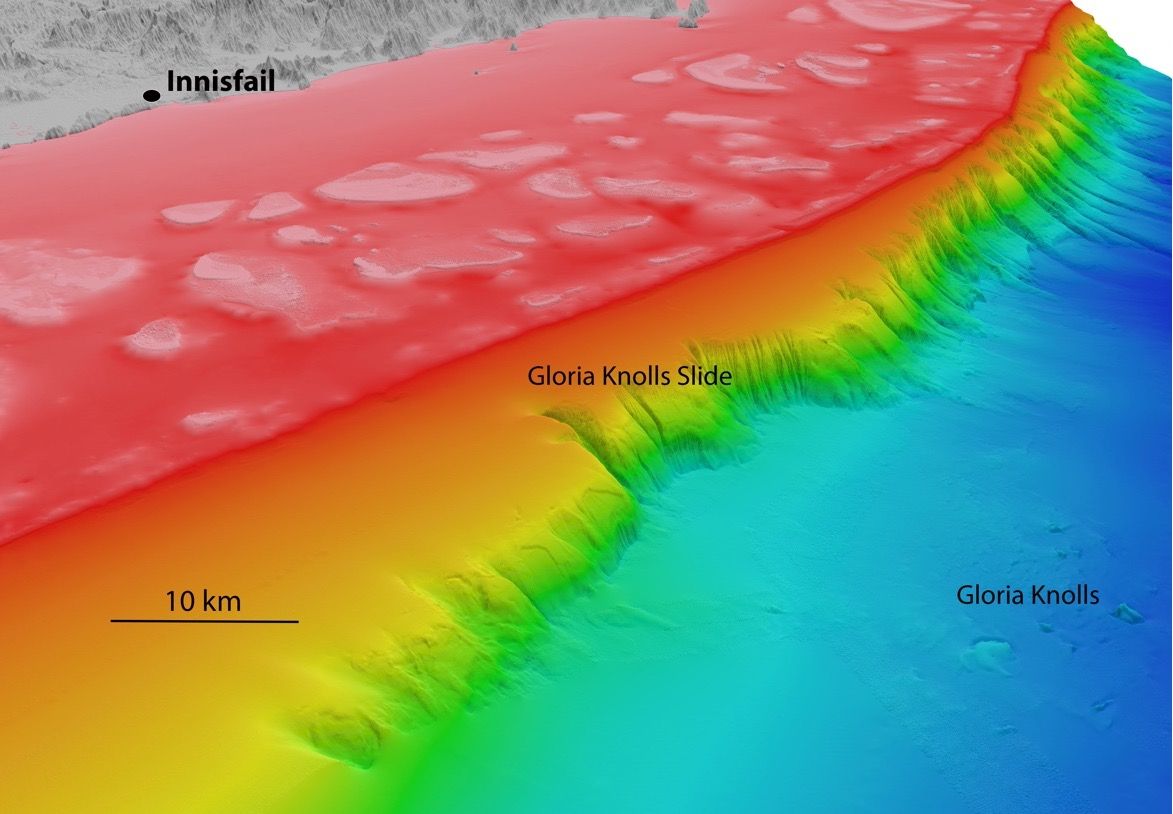

The researchers discovered the remnants of the giant submarine landslide while mapping the seafloor along a margin of the Great Barrier Reef using 3D multibeam sonar, in which sound waves are bounced off the seafloor. In one spot, called the Queensland Trough, which was supposed to be relatively flat, they found eight knolls, some of which rose 330 feet (100 meters) above the seafloor with lengths of more than 9,800 feet (3,000 m), the researchers said.

That series of knolls, now called the Gloria Knolls Slide complex, were the result of the ancient landslide, the researchers found.

Their geological sleuthing involved more seafloor mapping and coral sampling.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Samples from the knolls, which were submerged under nearly 4,000 feet (1,200 m) of water, revealed both living and fossil corals, Beaman said. The corals took up residence along the knolls sometime after the hilly terrain formed. "The oldest fossil coral we found, using isotope dating techniques, was 302,000 years old, therefore, making the landslide event that caused these knolls to be older than that age," Beaman told Live Science.

From the detailed, 3D maps of the area, the researchers reconstructed, or modeled, the landscape that would have existed before the slide. "So we can then simply do a before/after analysis of the volume of sediment that has been removed from this pre-slide surface," Beaman wrote.

The research, detailed in the March 2017 issue of the journal Marine Geology, was conducted by Beaman, lead author Angel Puga-Bernabéu of the University of Granada, Jody Webster of the University of Sydney, Alex Thomas of the University of Edinburgh, and Geraldine Jacobsen of the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organization.

The researchers noted that more research is needed to determine the risk of tsunamis related to these types of underwater landslides on the Queensland coast.

Original article on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.