Strange love: 13 animals with truly weird courtship rituals

For Valentine's Day, Live Science gathers together some of the more extravagant and outlandish courtship rituals in the animal kingdom.

- Giant pandas|Hostage-like situation

- Giraffes|Drinking pee

- Snails|Firing love darts

- Dinosaurs|Scraping and scratching

- Black widow spiders|Twerk or be eaten

- Sea slugs|Injecting sex hormones

- Pufferfish|Mystery circles

- Jumping spiders|Built-in glow sticks

- Marvelous Spatuletail |Tail whipping

- Bowerbirds|Illusion bachelor pads

- Mice|Ultrasonic love songs

- Songbird|Invisible tap dance

- Porcupines|Golden showers

On Valentine's Day, lovers who are eager to woo their partners show their affection with traditional gifts of red roses, heart-shaped boxes of chocolates or with romantic dinners at fancy restaurants. There's usually some effort involved, but pulling off a memorable Valentine's Day is easier — and generally safer — than some of the courtship rituals performed by other animal species.

For most animals, wooing comes with heightened personal risk. A male's showy displays, while attracting a female's attention, could also attract nearby predators, and fights between male rivals can also result in a date night with a body count. In some cases, winning a cannibalistic female's affections places the male at the top of the post-coital menu.

Many of the courting behaviors practiced by animals may seem strange to us, but as peculiar and risky as they are, they work just fine for their intended audiences. Here are a few examples of unusual and extreme courtship rituals in the animal kingdom.

Giant pandas

Pandas (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) are notoriously difficult to mate in captivity. Mating is no picnic in the wild, but for completely different reasons. In the first-ever footage of giant pandas getting intimate in the wild, filmmakers in China recorded an older male and a younger rival courting the same female, who was high above the ground in a tree.

The males had a tense standoff until the younger panda retreated. But the female wasn't ready to mate; upon descending, the female fought the older male and escaped. The two males followed her for weeks, growling at each other until one suitor dropped off and the female was ready to mate with the younger fellow.

It's possible that this prolonged male rivalry, including female "hostage"-taking, triggers female ovulation. So maybe that's why these black-and-white bears are so hard to breed in captivity, where male competition is nonexistent, according to the 2020 program "Pandas: Born to be Wild" that debuted the footage.

Giraffes

Male giraffes have to taste a lot of pee before they can do the deed. That's because the only way males (bulls) can tell if females (cows) are fertile is to determine if specific pheromones are present in her urine.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

First, the bull nudges the cows and sniffs her genitalia. Sometimes it takes a few nudges, but then the cow will widen her stance and urinate into the bull's mouth. Next, the bull does a "flehmen response" by curling back its upper lip and breathing in through its nostrils, using its sensitive vomeronasal organ above the roof of the mouth to smell his potential partner's pee. Other also animals smell pee when mating, but usually the female pees on the ground for the male to sniff. In the giraffe's case, they're way too tall to do it that way.

On average, bulls have to approach 150 females before finding one who is ready to mate, a 2023 study published in the journal Animals found.

Snails

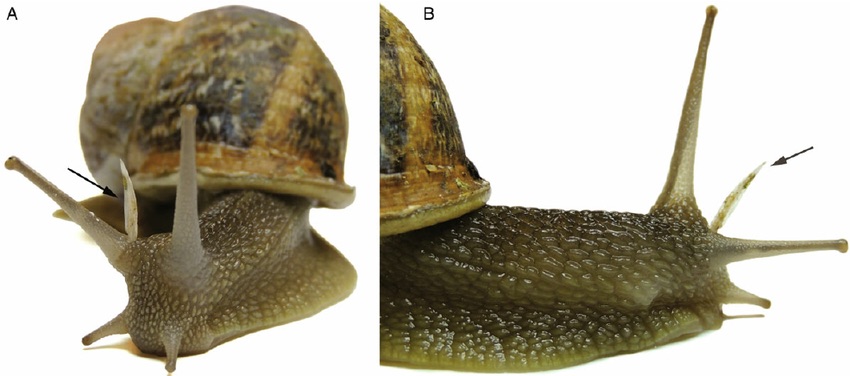

Look closely at these photos of land snail Cornu aspersum, and you'll see a small appendage close to the eyestalk. That tiny structure was propelled into the snail's head by its mate, delivering an infusion of a special mucus that prepares the snail for receiving an envelope full of sperm.

As land snails are hermaphrodites, either snail in a mating pair is capable of fertilizing the other, and both are equipped with "love darts" that they use to stab their partner — after they spend a bit of time circling around and touching each other with their muscular pseudopods.

Some snail species shoot single darts, some shoot multiple darts, and others use a single dart to repeatedly jab their mate for close to an hour, according to a 2006 study, published in the journal The American Naturalist.

Dinosaurs

Little is known about dinosaurs' mating habits, but evidence preserved in rocks in Colorado suggests that some dinosaurs practiced a ritual dance much like one performed by living birds.

Paleontologists found scrape marks — many dozens of them — in four sites that held remains of Cretaceous dinosaurs. In a 2016 study published in the journal Nature Scientific Reports, researchers explained that they saw distinct similarities between these scratches in the rock, and so-called "nest scrapes" created by certain types of male birds as part of their courtship displays.

Male birds across a number of ground nesting species — including sage grouse, puffins and various shore birds — scrape the ground in front of females, as if to demonstrate how good they would be at building a nest. They make dozens or even hundreds of scratches at a time, and usually accompany scraping with strutting, puffing themselves up, and fanning their tails.

Black widow spiders

Black widow (Latrodectus Hesperus) females are about twice as large as males, so the smaller suitors have to take some precautions when approaching a female's web, lest they be mistaken for prey and eaten before mating even gets underway.

Males stay safe by announcing their presence to the female with vigorous rump shaking.

As a male steps onto a female's web, he vibrates his abdomen, sending signals coursing along the silk strands. He advances, vibrates and pauses, advances, vibrates and pauses — a pattern distinctly different from the shorter, more irregular movements of trapped prey, researchers found in a study, published in the journal Frontiers in Zoology. The study authors also discovered that the vibrations that males produce are at a low amplitude, further distinguishing them from prey movements, which were more dynamic and percussive.

Sea Slugs

Hermaphroditic sea slugs possess both male and female sex organs, and when pairs come together to mate, they stab each other between the eyes with a needle-like appendage called a penile stylet, delivering a cocktail of prostate fluid. This tactic was described as "just weird" by a researcher who co-authored a 2013 study about the odd behavior, published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B.

Scientists are uncertain as to why exactly the slugs target this body area for stabbing, but they suspect that the hormonal injection may serve to increase the possibility of successful fertilization.

Pufferfish

"Mystery circles" on the ocean floor near Japan that measure about 7 feet (2.1 meters) in diameter were recently found to be made by a fish only 5 inches (12.7 centimeters) in length. The intricate symmetrical patterns were first noticed by divers in 1995, and in 2013 researchers described what created them: a species of pufferfish, with mating on its mind.

Males swim along the seafloor flapping their fins to sculpt the remarkably intricate ridges and valleys — a process that take seven to nine days — and then decorate them with shell fragments and sediment. After interested females are fertilized, they lay their eggs in the nest site at the center.

Though the structures are beautiful, scientists wrote in 2013 that the lines and shapes carved by the pufferfish serve to channel sediment particles, and likely don't serve an aesthetic purpose.

Jumping spiders

Body parts that reflect ultraviolet light help male jumping spiders in the Cosmophasis umbratica species catch females' eyes (all eight of them). Males lure the female spiders by striking poses that display these glowing patches prominently.

However, female C. umbratica spiders have a glowing trick of their own, possessing palps — a pair of appendages near the head — that fluoresce green in ultraviolet light, which they use to attract the males.

Both male and female spiders rely on these signals to tell who's in a mating mood, scientists discovered in a 2007 study published in the journal Science. When ultraviolet light was blocked and the spiders didn't glow, they lost interest in mating, the researchers found.

Marvelous Spatuletail

In one species of hummingbird — the marvelous spatuletail (Loddigesia mirabilis) — males attract females by whipping their lengthy tails back and forth.

And those tails are impressive, two of the four feathers measure about 6 inches (15 centimeters) in length — about twice as long as the birds' bodies — and are tipped with shiny iridescent "paddles," which the males whirl feverishly at likely mates.

Bowerbirds

Bowerbirds are known for building elaborate structures to attract female interest, even decorating their bowers with arrays of colored objects that appear to be selected and displayed for their aesthetic appeal.

But there's more to their arrangement than meets the eye. Researchers discovered that male bowerbirds construct their bachelor pads in such a way that when the male bird stands in front of it, he appears larger and more imposing to the female viewing him from outside.

And the birds that create the most successful illusions were the most popular with the females and the most likely to mate with them, scientists wrote in a 2012 study, published in the journal Proceedings for the National Academy of Sciences.

Mice

Male mice seeking to impress a mate sing unique high-pitched songs, vocalizing in the ultrasonic range. They produce these whistling sounds — which differ greatly from normal communication — by creating a type of feedback loop of airflow in the windpipe and larynx, according to a 2016 study published in the journal Current Biology. Scientists discovered the mechanism by shooting high-speed video of the mice's larynxes as they vocalized, capturing 100,000 frames per second.

Impressive though this technique may be, female mice are picky about which songs they like; they prefer tunes that differ from those sung by their relatives, according to an earlier study published in February 2014 in the journal PLOS One.

Red-cheeked cordon-bleu songbird

High-speed video recently revealed a mating dance performed by a species of songbird tapping their feet too quickly for the movements to be seen with the naked eye.

Blue-capped cordon-bleu songbirds (Uraeginthus cyanocephalus) — both males and females — were known to bob their heads and sing to each other during courtship, but a 2015 study published in the journal Scientific Reports was the first to capture the rapid tapping of their toes — and the birds tapped their feet faster if they were sharing the perch with a prospective mate, the scientists discovered.

Porcupines

Male North American porcupines must go to great lengths to secure the affections of females, which only go into estrus once a year for eight to twelve hours.

Prior to ovulating, the female secretes a fragrant (to a porcupine) vaginal mucus that lures males closer. The lucky male that finds her — and manages to chase away any rivals — stimulates ovulation by drenching her in an explosive jet of urine described as "a high speed projectile" by porcupine expert Uldis Roze, author of "The North American Porcupine" (Comstock Publishing Associates, 2009) and "Porcupines: The Animal Answer Guide" (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012).

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

- Laura GeggelManaging Editor