Sea Ice Hits Record Lows at Both Poles

Arctic temperatures have finally started to cool off after yet another winter heat wave stunted sea ice growth over the weekend. The repeated bouts of warm weather this season have stunned even seasoned polar researchers, and could push the Arctic to a record low winter peak for the third year in a row.

Meanwhile, Antarctic sea ice set an all-time record low on Monday in a dramatic reversal from the record highs of recent years.

Sea ice at both poles has been expected to decline as the planet heats up from the buildup of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. That trend is clear in the Arctic, where summer sea ice now covers half the area it did in the early 1970s. Sea ice levels in Antarctica are much more variable, though, and scientists are still unraveling the processes that affect it from year to year.

The large decline in Arctic sea ice allows the polar ocean to absorb more of the sun's incoming rays, exacerbating warming in the region. The loss of sea ice also means more of the Arctic coast is battered by storm waves, increasing erosion and driving some native communities to move. The opening of the Arctic has also led to more shipping and commercial activity in an already fragile region.

'Unusual Winter'

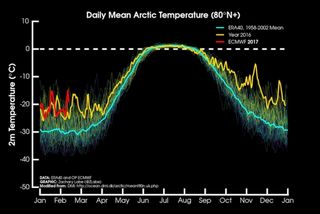

Temperatures in the Arctic have repeatedly spiked since the beginning of the freezing season last fall. The influx of warmth is caused by storms moving up from the Atlantic Ocean dragging warm air with them.

"This has been a most unusual winter," Julienne Stroeve, of the National Snow and Ice Data Center, which tracks sea ice levels, said in an email.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

During this latest event, temperatures above 80 degrees north latitude reached nearly 30 degrees Fahrenheit (15 degrees Celsius) above normal winter temperatures of about -22 degrees Fahrenheit (-30 degrees Celsius). Temperatures over the weekend peaked above even the maximum seen during last winter, another exceptionally warm one for the Arctic.

The temperature rise, along with the winds and waves churned up by the storm, can stymie sea ice growth and even cause local melt.

Sea ice coverage is particularly low in the Barents and Kara seas, which sit north of Scandinavia and Russia and have been in the path of those incoming storms. In Norway's Svalbard archipelago, which lies midway between mainland Norway and the North Pole, snows melted over the weekend as temperatures rose above freezing.

The Winter of Blazing Discontent Continues in the Arctic Watch 28 Years of Old Arctic Ice Disappear in One Minute 2016 'Arctic Report Card' Gives Grim Evaluation

With sea ice levels so low, it is possible that the Arctic will set a record low end-of-winter peak, which usually occurs in mid-March. If it does, this will be the third year in a row to set a record low maximum.

Stroeve said that this could be a sign that the significant losses of summer sea ice are starting to show up more in other seasons. As the fall freeze-up happens later and later, there is less time to accumulate winter sea ice.

Sea ice area isn't the only way to measure the health of Arctic sea ice; the thickness of the sea ice has also suffered during the repeated incursions of warmth.

Thin ice is more susceptible to melt come spring and summer, though it doesn't guarantee that summer will also see record lows. For example, despite record low levels of sea ice last summer, cool, cloudy weather kept melt somewhat in check. The season still finished with the second lowest summer minimum on record, though.

Antarctic Reversal

Antarctic sea ice is an altogether different beast. Instead of an ice-filled ocean surrounded by land, it is a continent surrounded by ocean that sees much more variability in sea ice levels from year to year for reasons that aren't fully understood.

For several of the past few years, the sea ice that fringed Antarctic reached record highs. That growth of sea ice could have potentially been caused by the influx of freshwater as glaciers on land melted, or from changes in the winds that whip around the continent (changes that could be linked to warming or the loss of ozone high in the atmosphere).

But this year, a big spring meltdown in October and November suddenly reversed that trend and has led to continued record low sea ice levels as the summer melt season progressed. On Monday, Antarctic sea ice dropped to an all-time record low, beating out 1997.

Sea ice has been particularly low in the Amundsen Sea region of Western Antarctica, thanks to unusually high temperatures there. But it's not clear what is ultimately driving this dramatic reversal in Antarctic sea ice, or whether it will be temporary or marks a longer-term shift.

"No one knows for sure what will happen, as there might be a rebounding from the very large decreases last year, or there might be a continuation of those decreases," Claire Parkinson, a NASA sea ice researcher said in an email. "Whichever way it turns out, the added information will probably help scientists to get a better handle on the likely causes."

You May Also Like: Coastal Cities Could Flood Three Times a Week by 2045 Conservatives Push Carbon Tax to Address Climate Crisis Dakota Pipeline Greenlighted As Fossil Fuels Move to Fore Food Security, Forests At Risk Under Trump's USDA

Originally published on Climate Central.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.