Ancient 'Nessie' Delivered Live Baby Sea Monsters

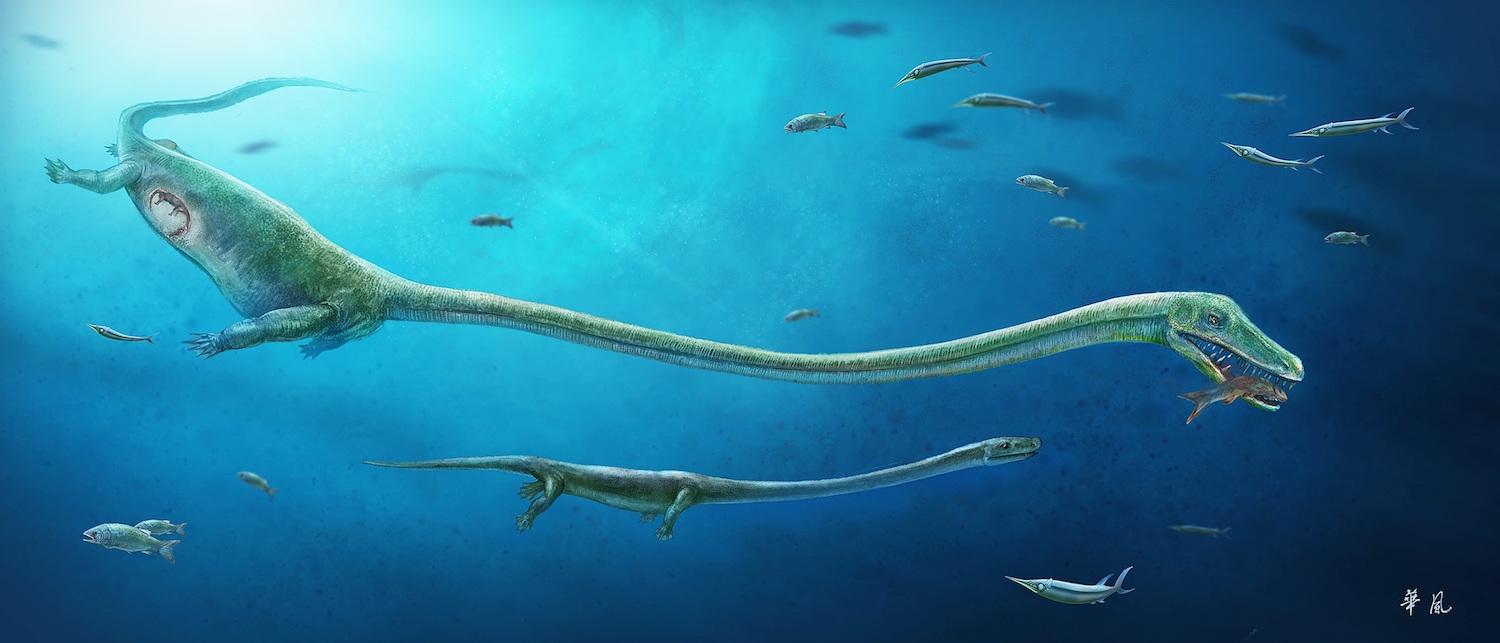

The "birth plan" of an ancient Nessie look-alike didn't involve laying a giant egg, but rather delivering a live baby sea monster, a new study finds.

Until now, researchers had thought that the fearsome marine reptile known as Dinocephalosaurus laid eggs, just as birds and crocodiles (its distant relatives) do. But the discovery of the remains of a pregnant, 245-million-year-old Dinocephalosaurus specimen in a Chinese fossil deposit indicates that the reptile gave live birth, the researchers said.

"This is the first-ever evidence of live birth in an animal group previously thought to lay eggs exclusively," said the study's lead researcher, Jun Liu, an associate professor of paleontology at the Hefei University of Technology in China. [Image Gallery: Ancient Monsters of the Sea]

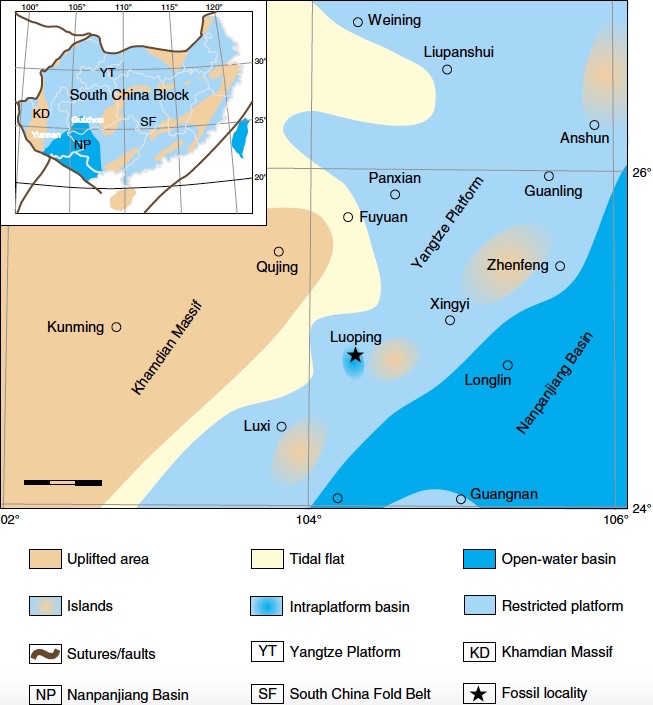

Researchers discovered the specimen of the pregnant Dinocephalosaurus in southwestern China's Luoping Biota National Geopark in 2008. During its lifetime in the middle Triassic period, the 13-foot-long (4 meters) marine reptile would have swum throughout the shallow seas of ancient southern China.

Dinocephalosaurus had a long neck and sharp teeth. "It was a fish eater, snaking its long neck from side to side to snatch its prey," Liu told Live Science. "It looks superficially like the legendary Nessie."

Ancient embryo

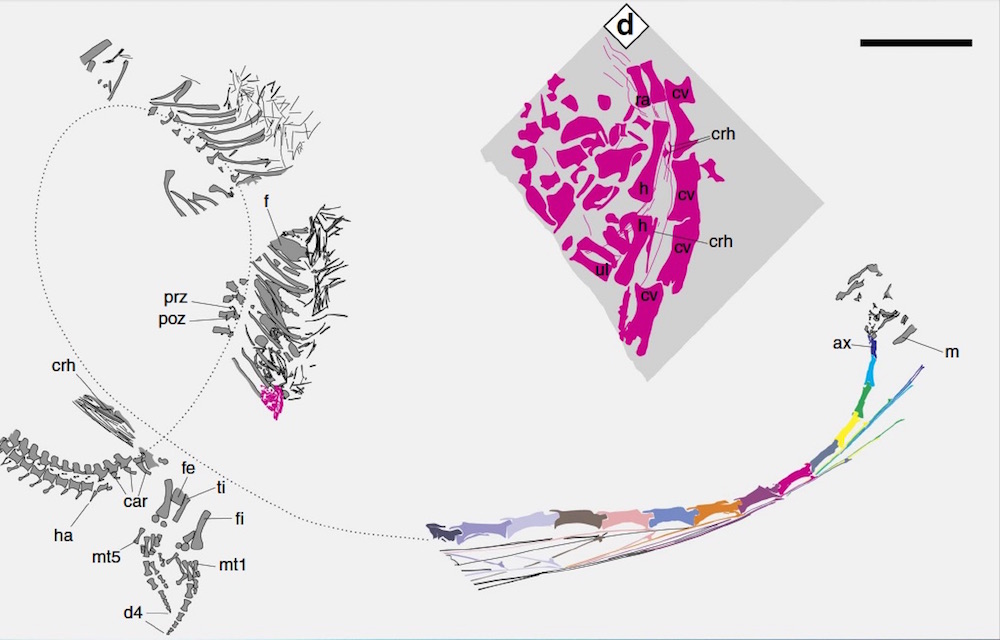

The researchers discovered a fossilized Dinocephalosaurus embryo in the mother's abdomen. The fetus was small — about 12 percent of its mother's body size — but large enough for scientists to discern that its anatomy (for instance, a long neck and elongated ribs) was similar to that of the adult Dinocephalosaurus, the researchers said.

Still, the researchers went to great lengths to determine that the bundle of bones was, in fact, an embryo. First, they noted that the embryo was enclosed within the mother's body, which excluded the possibility that a foreign animal fell on top of her and then fossilized. Second, the embryo's neck was pointing forward. Usually, sea creatures swallow prey headfirst; the mother even had a partially digested fish, whose head was facing backward in her abdomen, the researchers noted.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The neck-forward position of the embryonic skeleton suggests that the included skeleton was not ingested prey, but was an embryo," the researchers wrote in the study.

Finally, the embryo was curled in a fetal position, just like other known vertebrate embryos during development, the researchers said.

Egg-laying animals typically deposit eggs holding embryos that are much less developed than the one found inside the mother Dinocephalosaurus, the research team noted. In addition, the researchers said that they did not see any evidence of an eggshell near the embryo, further supporting the idea that the Dinocephalosaurus gave live birth, they said.

Reptilian evolution

Dinocephalosaurus was an archosauromorph (Greek for "ruling lizard form"), a relative of the group that includes crocodiles, pterosaurs and dinosaurs, including birds. The new discovery pushes back evidence of reproductive biology in the Archosauromorpha group by 50 million years, Liu said.

In addition, the discovery solves a mystery about egg laying in most archosauromorphs. Previously, researchers were unsure whether archosauromorphs had genetic or developmental barriers preventing live birth, but now they know there isn't a barrier — most archosauromorphs just evolved to lay eggs, Liu said. [Photos: Ancient Pterosaur Eggs & Fossils Uncovered in China]

The finding is an "extraordinary" one, and demonstrates how "evolution never really attains the optimal solution," said Kenneth Lacovara, a professor of paleontology and the dean of the School of Earth and Environment at Rowan University in New Jersey, who was not involved in the study. "It obtains the best solution possible based on the current situation."

The finding shows that "egg laying in the group that spans crocodiles to birds is not a deficit of their nature," Lacovara told Live Science. "It appears to be a strength. The alternative was possible, but that was not selected for."

Moreover, the fossils show that "Dinocephalosaurus determined the sex of its babies genetically," Liu said. "This is a noteworthy finding given that its closest extant [living] relatives, turtles and crocodilians, determine the sex of their offspring by environmental temperatures."

Live birth (known as viviparity) has evolved independently at least 115 times in living lizards and snakes, and at least once in the common ancestor of mammals, the researchers said. However, Dinocephalosaurus is hardly the only ancient marine reptile that gave live birth; a 182-million-year-old ichthyosaur fossil shows that a mother died during a breech birth, Live Science reported previously.

The new study was published online today (Feb. 14) in the journal Nature Communications.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.