Rare Leptospirosis Cases in NYC: 5 Things to Know

Three people in New York City recently became sick with a rare bacterial disease called leptospirosis that they might have contracted from rats, according to the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH).

All three cases occurred in a one-block section of a neighborhood in the Bronx called the Concourse over the past two months, the DOHMH said in a statement. Although New York City typically sees about one to three cases of leptospirosis per year, this is the first time that health officials have identified a cluster of leptospirosis cases (meaning more than a single case occurring in the same place around the same time) in the city, the DOHMH said.

All three people were hospitalized with kidney and liver failure, and one person died as a result of their infection, DOHMH said. [10 Deadly Diseases That Hopped Across Species]

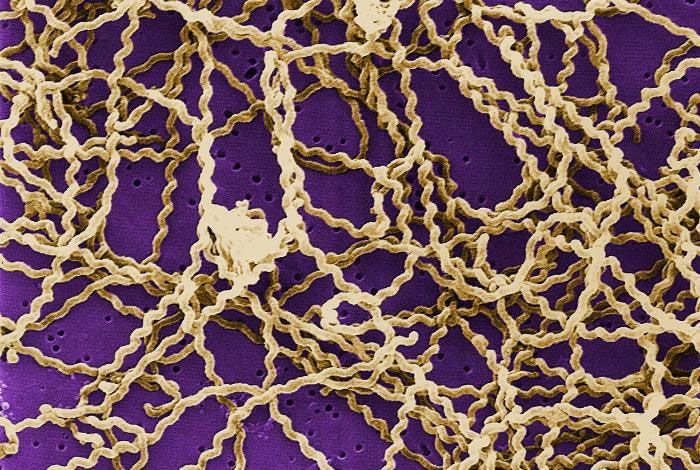

Leptospirosis is caused by a spiral-shaped bacterium known as Leptospira, which can infect animals and people. Here are five important things to know about leptospirosis.

How do people get leptospirosis?

People can become infected with Leptospira bacteria when they come into contact with the urine of infected animals, or with an environment that's been contaminated with urine from infected animals, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The bacteria can enter the body through broken skin (such as a cut or scratch), or through the mucous membranes in the eyes, nose and mouth, the CDC said.

People may contract leptospirosis when they swim in water that's been contaminated with infected animal urine, or if they have contact with contaminated food or soil, the CDC said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For the New York City cases, health officials suspect that the people became infected through contact with urine from rats, because most cases in New York City are linked with exposure to rats or rat-infested environments, the DOHMH said.

How common is leptospirosis?

Human cases of leptospirosis are rare in the United States. According to the CDC, only about 100 to 200 leptospirosis cases are reported each year in the United States. About 50 percent of all U.S. leptospirosis cases occur in Hawaii, the CDC said.

The largest outbreak of leptospirosis ever recorded in the United States occurred in 1998, when more than 1,000 athletes participating in summer triathlons in Illinois and Wisconsin were potentially exposed to the bacteria, and 110 became infected, according to the CDC. [10 Bizarre Diseases You Can Get Outdoors]

How severe are the symptoms?

Some people infected with Leptospira bacteria may have no symptoms at all, according to the CDC. Others may experience a high fever, chills, muscle aches, vomiting, diarrhea and photophobia (eye discomfort when exposed to bright light). In severe cases, the infection can lead to kidney damage, brain inflammation, liver failure and death, the CDC said.

How is leptospirosis treated?

Leptospirosis can be treated with antibiotics — usually doxycycline or penicillin. Treatment should begin as early as possible to reduce the severity and duration of the disease, the DOHMH said.

Can leptospirosis be prevented?

To avoid becoming infected with the Leptospira bacteria that cause leptospirosis, people should wear protective clothing or footwear if they are exposed to water or soil that might have been contaminated with animal urine, the CDC said. For example, people should wear shoes when they take their garbage to a trash compactor room, and avoid contact with areas in which rats might have urinated, according to The New York Times.

People should also avoid swimming or wadding in water that may be contaminated with animal urine, and avoid swallowing water in lakes and rivers, the CDC said.

Taking measures to prevent rodent infestations (for example, by setting up rodent traps and sealing holes in your home) can also prevent some leptospirosis cases, the CDC said.

Finally, pets should be vaccinated against leptospirosis, although the vaccine is not 100 percent effective at preventing the infection, the CDC noted.

Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.