Special Wavy Nerves Help Whales Take Big Gulps Without Pain

Being a baleen feeder isn't easy. When baleen whales — like the enormous blue whale — gulp up a mouthful of water to filter for food, a pouch of skin under their chins stretches to accommodate the load. This stretch should hurt, but new research finds that whale nerves are specially adapted to prevent these giant beasts from feeling pain.

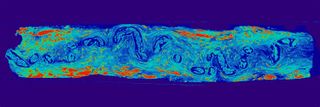

A study of fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus) finds that their nerves have two levels of waviness. The whales' nerves are coiled like an old-fashioned telephone cord so that they can still work when stretched. Within the coils is a second level of waviness that allows the nerve fibers to twist around the curves without stretching.

"Waviness in nerves per se isn't surprising, but we saw what appeared to be tight hairpin turns in the tissue that we thought couldn't be right — nerves shouldn't be able to bend so tightly," study leader Margo Lillie, a zoologist at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, said in a statement. [Images: Whales & Sharks From Above]

Filter feeders

Lillie and her colleagues from the University fo British Columbia were interested in rorqual whales, a group of baleen whales known for their pleated throats. The pleats allow the whales to take in huge gulps of water, which they then push out of their mouths with their tongues, past their bristle-like baleen. The water gets forced out, while prey gets trapped and swallowed.

In the fin whale, the throat can expand to 162 percent of its resting circumference when feeding, Lillie and her colleagues wrote in the journal Current Biology. That's a big change for nerves to absorb, so the researchers decided to find out how whale nerves cope.

The researchers dissected fin whale nerves, which are covered with a collagen sheath. Upon opening the collagen sheath, the coiled nature of the nerve was obvious, the researchers reported.

Next, the researchers used a micro-computed tomography (CT) scanner to get a closer look at the nerve structure. Each nerve was actually a bundle of nerve fibers called fascicles, which had their own small-scale waviness, the scientists found. The wavy structure of the fascicles was most apparent on the inside of the larger coils.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"This made sense from the engineering theory of bending strain, which tells us that when a rod is bent, the material on the outside is stretched and on the inside compressed," Lillie said.

Two layers of waves

Two tiers of waviness allow the fascicles to bend within the main nerve core without damage. When the whale has a mouthful of seawater, Lillie and her colleagues wrote, the fascicles are stretched straight, as is the main nerve. As the whale empties its feeding pouch, the fascicles are the first to start folding up. The main nerve relaxes a bit during this phase as the fascicles lend it some slack, but it stays straight.

As the whale empties its pouch further, the nerve relaxes into its next phase. The main nerve core begins to coil, too. The twists and turns of the main nerve would normally damage the fascicles within, but their coils allow them the slack to traverse the bends of the main nerve without pain or injury, the scientists said.

The researchers now hope to study other stretchy tissues from different animals to find out if whales have hit on a unique way to protect their nerves, or if other species share similar anatomy.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.