Cholera, Other Illnesses May Spread with Climate Change

ATLANTA — Infectious-disease specialists are concerned that climate change is contributing to the spread of certain diseases, including the germs that cause cholera and other diarrheal illnesses.

Data now suggest that the locations where certain pathogens are found have changed, said Dr. Glenn Morris, the director of the Emerging Pathogens Institute at the University of Florida. Morris gave a talk here today (Feb. 16) at the Climate & Health Meeting, a gathering of experts from public health organizations, universities and advocacy groups that addressed the health impacts of climate change.

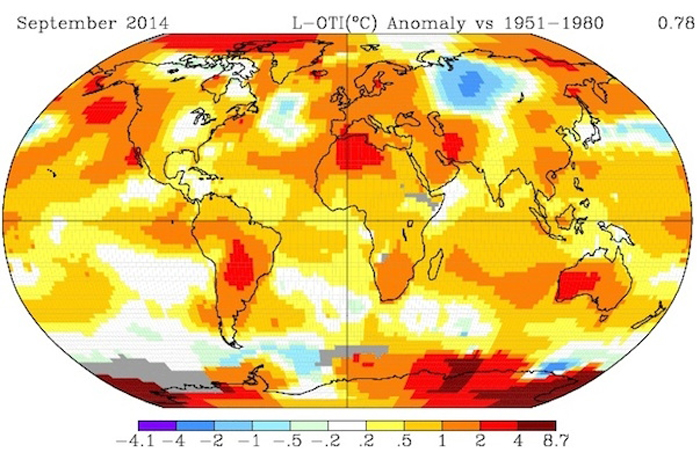

Pathogens tend to live in places that have ideal sets of conditions, Morris said. For example, these bugs may have evolved to function best within certain temperature ranges, he said. And as climate change occurs and global average temperatures rise, researchers are beginning to see some indications that the areas where certain pathogens can live are shifting, he said. [5 Ways Climate Change Will Affect Your Health]

"We are seeing the spread of pathogens to new ecological niches," Morris said.

And the pathogens that live in water are among scientists' top concerns, Morris told Live Science.

An increase in sea temperatures, of even just a degree or two, can have a large impact on an organism's ability to live and multiply, Morris said. In many cases, as waters warm, pathogens will be able to expand into new areas. On the other hand, if water temperatures in a region increase too much, the number of pathogens there may decrease, Morris added.

Vibrio and algal blooms

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

One group of bacteria, called Vibrio species, are particularly well-studied, Morris said. Vibro bacteria are responsible for cholera and other diarrheal diseases. Although cholera can be treated by rehydration according to the World Health Organization, the disease can still be fatal if not treated quickly enough.

Vibriobacteria live in seawater, and with sea temperatures rising, scientists have recently observed a northward shift in the bacteria's range, he said. In addition, diseases such as cholera often spread following events like flooding, which may become more common with climate change, Morris said.

Other waterborne diseases can come from harmful algal blooms, which are caused by toxic forms of algae, Morris said. Algal blooms have been linked to illnesses such as ciguatera, which people get from eating fish that contain toxins produced by the algae Gambierdiscus toxicus, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Another illness linked to harmful algal blooms is amnesic shellfish poisoning, which is caused by eating contaminated shellfish.

These harmful algal blooms are showing up in places where they previously didn't occur, including the Pacific Northwest, Alaska and Maine, Morris said.

But what about mosquitos?

Morris noted that there have also been some concerns about mosquito-borne diseases, because of evidence suggesting that certain species of the insect are moving farther north than they used to. But it's unclear what impact this will have in the long term, Morris told Live Science. He noted that in developed countries, including U.S., many aspects of homes help protect people against mosquito bites, such as the use of window screens and air conditioning. [6 Unexpected Effects of Climate Change]

While the illnesses Morris noted in his talk are all known diseases, they can still pose public health challenges when they move into parts of the world where they haven't occurred before, he said.

"We've always thought about tropical areas as having particularly significant problems with infectious diseases," but "we're starting to see some greater indications that those diseases may be creeping up here" in the U.S., he said.

Morris said that the U.S. can handle those diseases, but the bigger concern is that pathogens are always evolving. Mcroorganisms may be able to change over time, "and increasingly take advantage of conditions that may not have been present before," he said.

Originally published on Live Science.