Teensy "living" circuits based on DNA could lead to new ways for scientists to look inside cells and even see chemical reactions such as photosynthesis. However, to create such DNA devices, there has to be a way to run electricity through them. Until now, that has been a limiting factor.

But now, scientists have turned tiny snippets of DNA into molecular "on" switches that get electricity flowing on a miniscule scale. The molecular switches act on a scale 1,000 times smaller than a strand of hair, meaning they could be used to create tiny, cheap molecular devices, the researchers report in a new study.

The secret to creating these biological electrical switches was tweaking the letters that make up the genetic code.

"Charge transport is possible in DNA, but for a useful device, one wants to be able to turn the charge transport on and off," Nongjian Tao, a researcher with The Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University, said in a statement. "We achieved this goal by chemically modifying DNA." [Top 10 Inventions That Changed the World]

Biological circuits

The idea of creating tiny machines from the building blocks of life isn't new. Researchers have looked at DNA as more than a means of storing the instructions for building and maintaining life. Some researchers have manipulated DNA to act as a hard drive; for instance, researchers have stored the entire works of Shakespeare in the genetic code. Other researchers have tried to transform DNA into tiny computers. And some work has showed it is possible to allow electricity to flow through DNA. However, the key to using DNA for electrical devices is the ability to turn the electricity on and off.

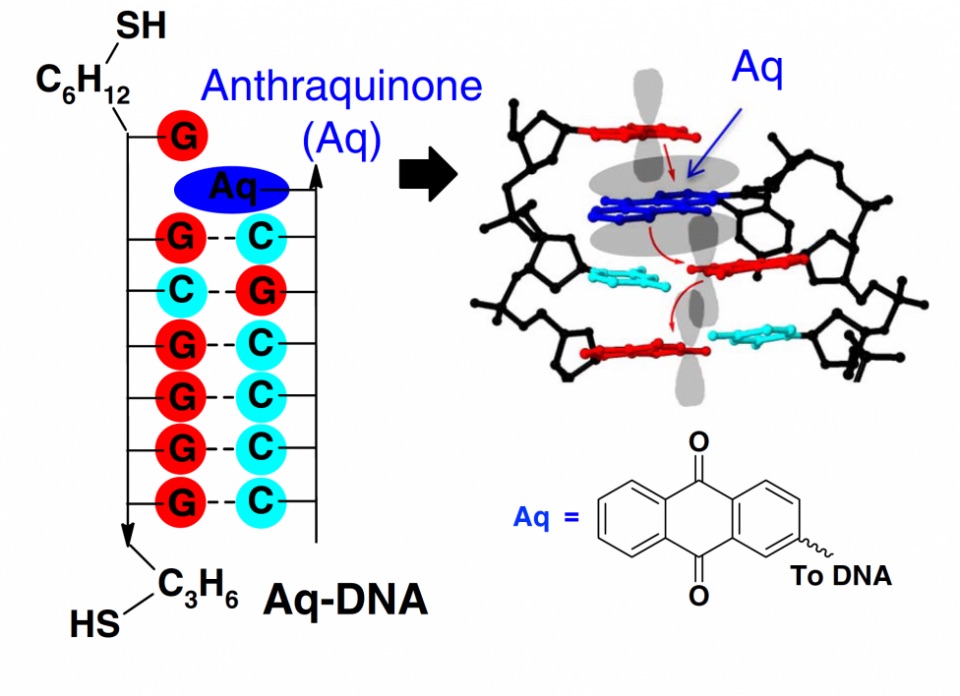

To achieve this objective, Tao and colleagues looked at anthraquinones, naturally occurring compounds made up of carbon, oxygen and hydrogen molecules that are arranged in three ring structures. Anthraquinones have two key properties. First, they can be slipped between the A, G, T and C base pairs that make up the letters of DNA. Second, they can fuel what are called redox reactions, or reduction-oxidation reactions, in which some molecules gain electrons while others lose them. This electron transfer allows the body to convert energy stored in chemical bonds into the electrical pulses that course through the brain, heart and other cells.

After the researchers inserted anthraquinones between the letters of DNA, creating a DNA switch, they measured the modified DNA electrical conductance. To do this, they placed the DNA switch inside a scanning tunneling microscope and repeatedly nudged the DNA with the electrode tip of the microscope.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They found that it was possible to reversibly switch the DNA to either the "on" or the "off" state, depending on whether the anthraquinone group had the highest possible number of electrons or the lowest, the researchers reported Monday (Feb. 20) in the journal Nature Communications. From there, the team created a 3D map of how electrical conductance varied with the state of the anthraquinone molecules.

The modified DNA could be used to create nanoscale electrical devices.

"We can also adapt the modified DNA as a probe to measure reactions at the single-molecule level. This provides a unique way for studying important reactions implicated in disease, or photosynthesis reactions for novel renewable energy applications," Tao said. "We are particularly excited that the engineered DNA provides a nice tool to examine redox-reaction kinetics, and thermodynamics [at] the single-molecule level."

Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.