Astronomers have never seen anything like this before: Seven Earth-size alien worlds orbit the same tiny, dim star, and all of them may be capable of supporting life as we know it, a new study reports.

"Looking for life elsewhere, this system is probably our best bet as of today," study co-author Brice-Olivier Demory, a professor at the Center for Space and Habitability at the University of Bern in Switzerland, said in a statement.

The exoplanets circle the star TRAPPIST-1, which lies just 39 light-years from Earth — a mere stone's throw in the cosmic scheme of things. So speculation about the alien worlds' life-hosting potential should soon be informed by hard data, study team members said. [Images: The 7 Earth-Size Worlds of TRAPPIST-1]

"We can expect that, within a few years, we will know a lot more about these planets, and with hope, if there is life there, [we will know] within a decade," co-author Amaury Triaud, of the Institute of Astronomy at the University of Cambridge in England, told reporters on Tuesday (Feb. 21).

A bizarre alien system

TRAPPIST-1 is an ultracool dwarf star that's only slightly larger than the planet Jupiter and about 2,000 times dimmer than the sun.

The research team, led by Michaël Gillon of the University of Liège in Belgium, originally studied the star using the TRAnsiting Planets and PlanetesImals Small Telescope (TRAPPIST), an instrument at the La Silla Observatory in Chile. (This explains the star's common name; the object is also known as 2MASS J23062928-0502285.)

TRAPPIST spotted regular dimming events, which the team interpreted as evidence of three different planets crossing the face of, or transiting, the star. In May 2016, Gillon and his colleagues announced the existence of these three alien worlds, called TRAPPIST-1b, TRAPPIST-1c and TRAPPIST-1d. All three, the team reported, are roughly the size of Earth and may be capable of supporting life.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The astronomers kept studying the system, using TRAPPIST and a number of other telescopes on the ground. This follow-up work suggested that the supposed TRAPPIST-1d transits were actually caused by more than one planet, and also revealed evidence of additional possible worlds in the system.

A three-week observation campaign by NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope in September and October 2016 helped clear all of this up. Spitzer's transit data confirmed the existence of planets b and c, but revealed that three worlds are responsible for the originally detected "TRAPPIST-1d" signal. And Spitzer also spotted two more exoplanets in the system, for a total of seven.

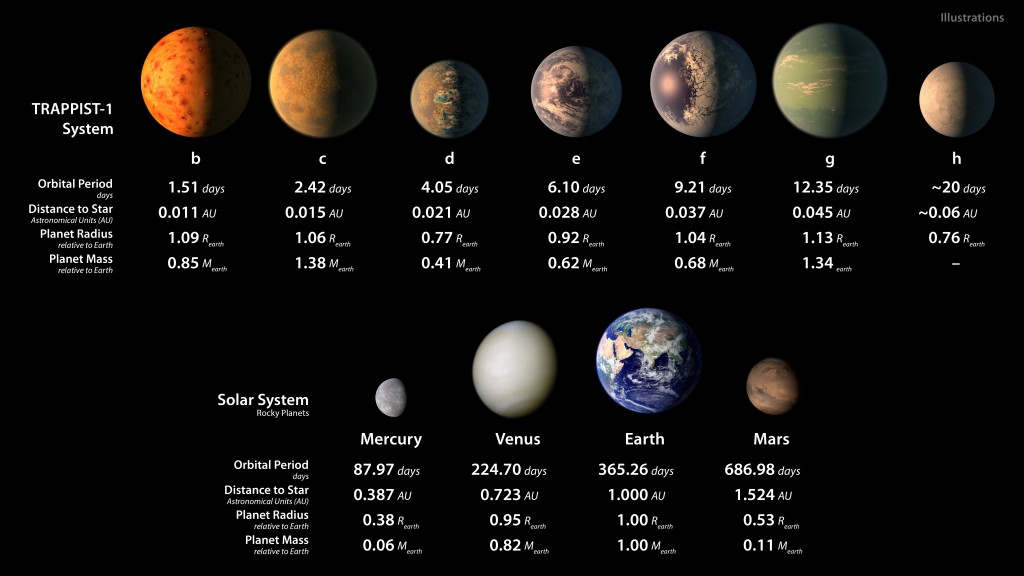

These seven worlds — which Gillon and his colleagues announced in the new study, published online today (Feb. 22) in the journal Nature — are all roughly Earth-size. The smallest is about 75 percent as massive as Earth, while the largest is just 10 percent heftier than our planet, the researchers said.

"This is the first time that so many planets of this kind are found around the same star," Gillon said in Tuesday's news conference. [Gallery: The Strangest Alien Planets]

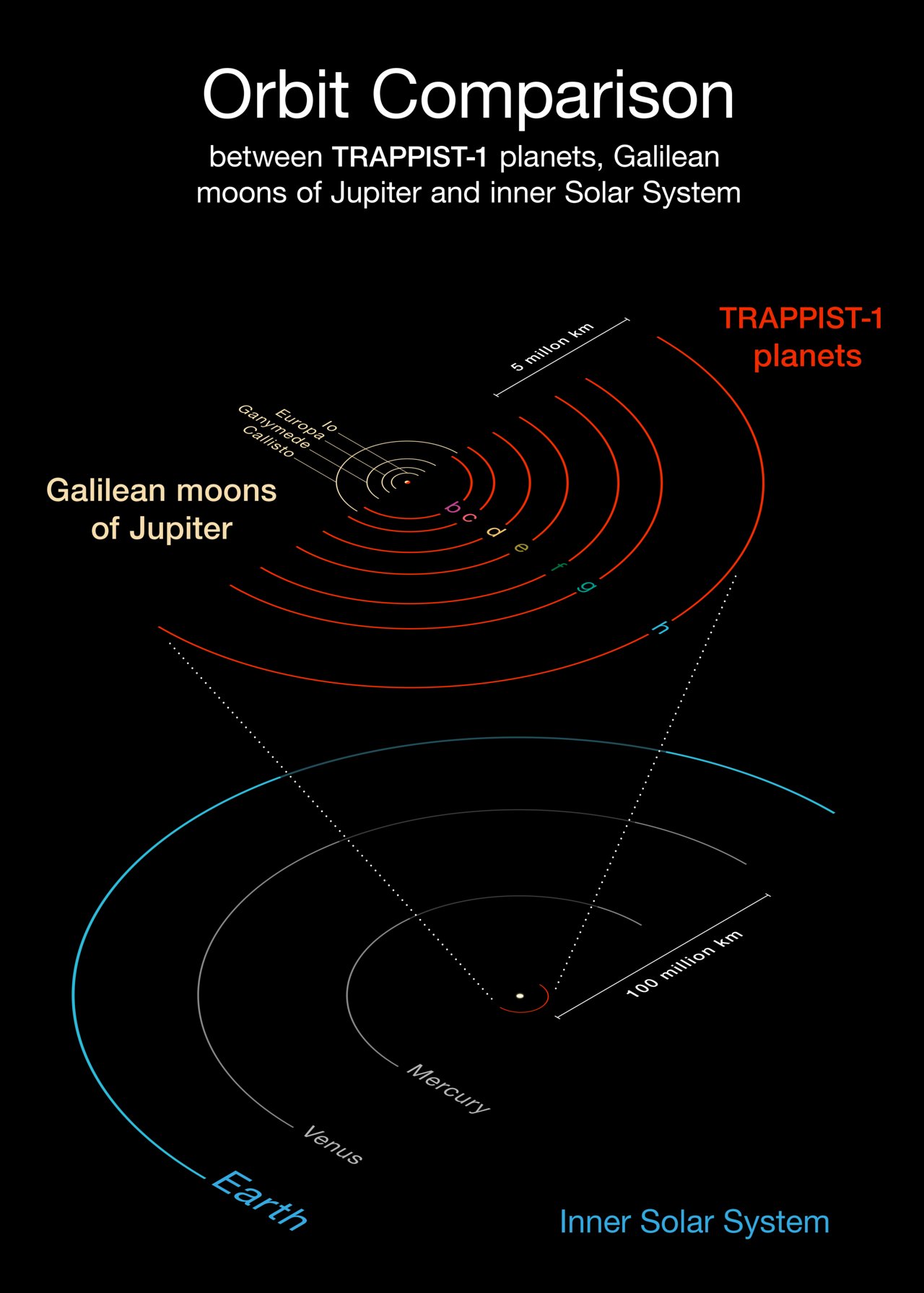

All seven alien worlds occupy tight orbits, lying closer to TRAPPIST-1 than Mercury does to the sun. The orbital periods of the innermost six worlds range from 1.5 days to 12.4 days; the outermost planet, known as TRAPPIST-1h, is thought to complete one lap in about 20 days. (Spitzer spotted just one transit by TRAPPIST-1h, so its orbital path is not well-known.)

The six inner planets are in near-resonance, meaning their orbital periods are related to each other by a ratio of two small integers. This arrangement suggests that the worlds formed farther out in the system and then migrated in to their current positions, study team members said.

Data gathered by the various telescopes suggest that all six inner planets are rocky, like the Earth; not enough is known about planet h to determine its composition.

Habitable worlds?

Because the seven alien worlds orbit so tightly, they're probably all tidally locked, Gillon said. That is, they likely always show the same face to their host star, just as Earth's moon only shows the "near side" to us.

And powerful gravitational tugs, both from TRAPPIST-1 and neighboring planets, could heat up the worlds' insides considerably, leading to lots of volcanism, especially on the innermost two worlds, the researchers added.

Despite these characteristics — extreme closeness to their star and tidal locking — the TRAPPIST-1 system is a promising place to search for E.T., study team members said.

TRAPPIST-1 is so dim and cool that its "habitable zone" — that just-right range of distances where liquid water could exist — is quite close to the star. And even tidally locked planets are thought to be potentially habitable, as long as they have atmospheres that can transport heat from the day side to the night side, Gillon said.

"You'd have just a [temperature] gradient, but it's not catastrophic for life," he said.

Indeed, modeling work performed by the team suggests that three of the seven TRAPPIST-1 planets (e, f and g) are in the habitable zone. And it's possible that, given the right atmospheric conditions, water — and, by extension, life as we know it — could exist on all seven, Gillon said.

Such speculation is preliminary, he and other team members stressed; more data will be needed before the TRAPPIST-1 planets' habitability can be gauged with confidence. Such work is already underway. The team has been studying the worlds' atmospheres with NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, for example.

Detailed characterization — and the search for signs of possible life, such as oxygen and methane — will have to wait until more powerful instruments come online, Triaud said. But that wait shouldn't be long: NASA's $8.8 billion James Webb Space Telescope is slated to launch in late 2018, and huge, capable ground-based scopes such as the European Extremely Large Telescope and the Giant Magellan Telescope are scheduled to come online in the early to mid-2020s.

"I think that we've made a crucial step toward finding [out] if there is life out there," Triaud said. "Here, if life managed to thrive, and releases gases similar to that that we have on Earth, then we will know."

Alien skywatching

If there were life-forms on one or more of the TRAPPIST-1 worlds, what would they see? Because of the star's dimness, even daytime skies would never get brighter than Earth's are just after sunset, Triaud said. (Still, the air would be warm, because most of TRAPPIST-1's light is radiated in infrared, not visible, wavelengths.) And everything would be suffused in a sort of salmon-colored glow.

"The spectacle would be beautiful, because every now and then you would see another planet, maybe about as big as twice [Earth's] moon in the sky, depending on which planet you were on," Triaud said.

Future work may help determine just how common such seemingly exotic vistas are in the sun's neck of the cosmic woods.

"About 15 percent of the stars in our neighborhood are very cool stars like TRAPPIST-1," Demory said in the same statement. "We have a list of about 600 targets that we will observe in the future."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.