Colossal (and Growing) Crack in Antarctic Ice Shelf Seen in New Video

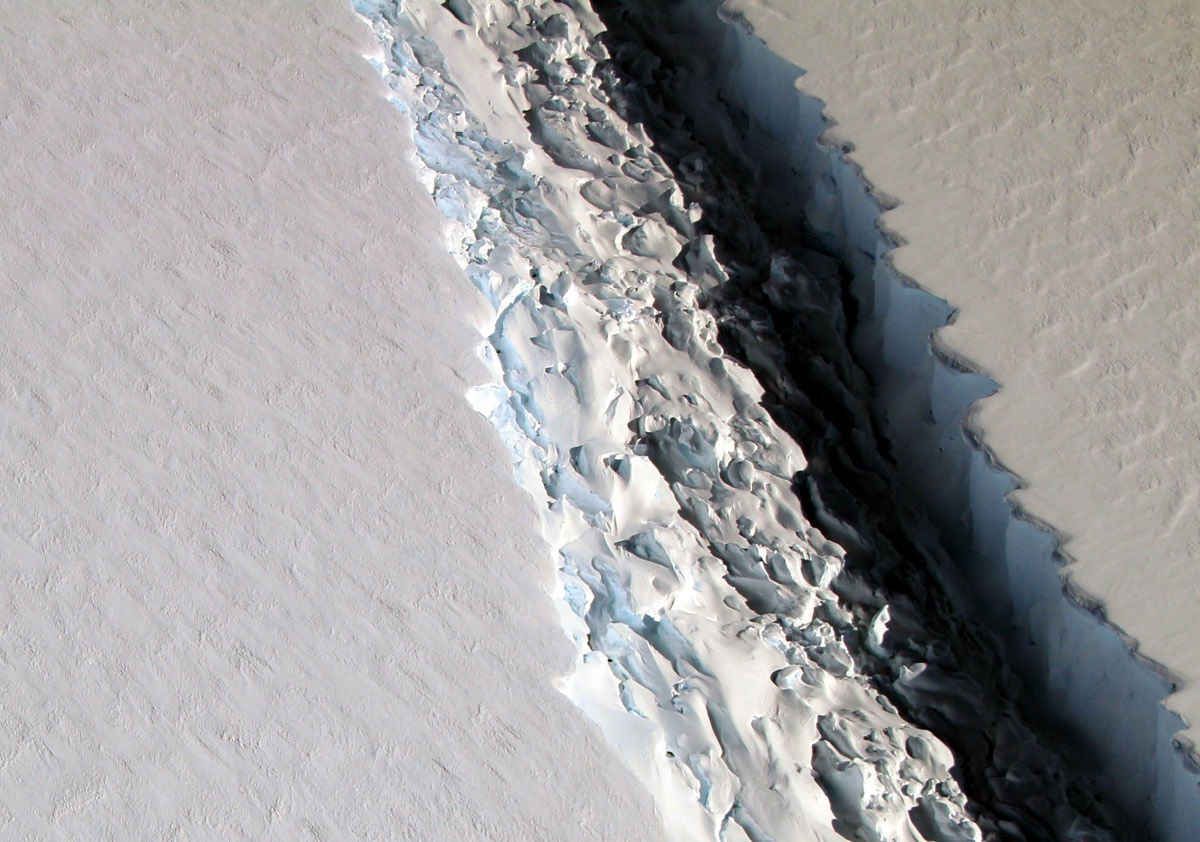

A giant crack that could release a chunk of ice larger than the state of Rhode Island into the sea was captured in stunning detail in new video footage of Antarctica's Larsen C Ice Shelf.

The stunning overhead video shows a lengthy and wide gash in the never-ending white of the ice shelf, a rift estimated to have grown to nearly 109 miles (175 kilometers) long, based on satellite data released in January. The rift is about 1,500 feet (460 meters) wide.

Scientists estimate it could take just months for that huge iceberg to break off the shelf. [Images of Melt: Earth's Vanishing Ice]

"Although the event could occur anywhere from days to years, the iceberg is likely to break free within the next few months simply because the leverage of 175 km [109 miles] of iceberg on [around] 20 km [12 miles] of what remains connected to the ice shelf is overwhelming," MIDAS scientists wrote in a blog post on Feb. 6. "We are watching with bated breath."

The British Antarctic Survey shot the video on Feb. 8 during a flight in a Twin Otter aircraft to collect scientific equipment for scientists participating in the MIDAS Project, focused on monitoring ice shelves.

"They were collecting data loggers for us that were measuring the temperature deep within the shelf," MIDAS scientist Adrian Luckman, of Swansea University in the United Kingdom, told Live Science in an email.

The glaciologists who are studying the seafloor beneath the Larsen C shelf typically set up camp on the ice. However, because a calving event seems imminent, they instead made one-off trips, flying back and forth from the Rothera Research Station in the United Kingdom using a Twin Otter aircraft.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Like other ice shelves, the Larsen C is a floating extension of a land-attached glacier that is slowly creeping toward the ocean. The collapse of an ice shelf doesn't lead to rising seas since it's already floating on the water, but it can accelerate the flow of the glacier it's buttressing toward the sea.

"Iceberg calving is a normal part of the glacier life cycle, and there is every chance that Larsen C will remain stable and this ice will regrow," Paul Holland, with the British Antarctic Survey, said in a statement. "However, it is also possible that this iceberg calving will leave Larsen C in an unstable configuration. If that happens, further iceberg calving could cause a retreat of Larsen C. We won't be able to tell whether Larsen C is unstable until the iceberg has calved and we are able to understand the behavior of the remaining ice."

The Larsen Ice Shelf, which is divided into areas that scientists have labeled A, B and C, sits on the northeast coast of the Antarctic Peninsula on the Weddell Sea. Named after Norwegian explorer Carl Anton Larsen, the ice shelf has lost about 75 percent of its mass since 1995, according to the National Snow and Ice Data Center.

In 1995, a huge piece of ice — covering an area of 579 square miles (1,500 square kilometers) — calved from the Larsen A Ice Shelf. And in 2002, a 1,255-square-mile (3,250 square km) ice chunk from the Larsen B shelf cracked free. While the icebergs themselves didn't raise sea levels, the resulting flow of ice from the glacier behind them can do just that, according to the statement.

"The stability of ice shelves is important because they resist the flow of the grounded ice inland," Holland said in the statement.

The gaping rift in the ice shelf is likely part of a natural cycle in the Antarctic, and not a result of climate change. "We have no evidence to link this event to climate change. Although the general southward progression of ice shelf decay down the Antarctic Peninsula has been linked to a warming climate, this rift appears to have been developing for many decades, and the result is probably natural," MIDAS scientists wrote in the blog post.

Original article on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.