Microbes in Glittering Crystal Cave Revived After 10,000 Years

Microbes that may be between 10,000 and 50,000 years old have been revived from the inside of enormous, glittering crystals from a Mexican cave.

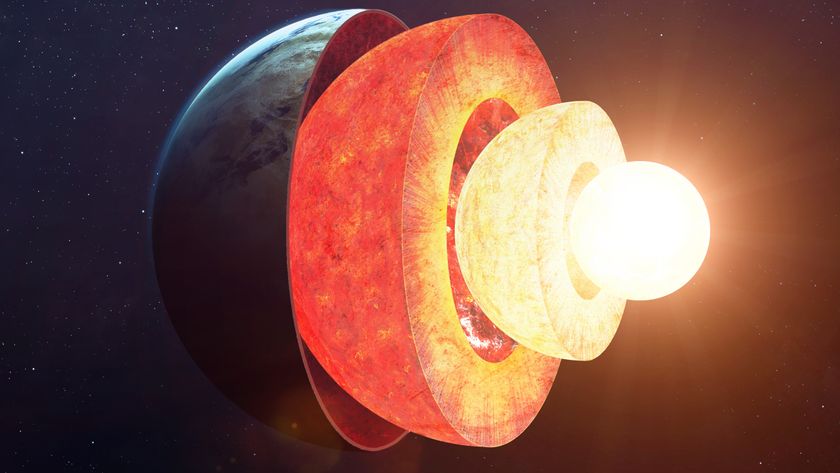

The microbes come from the Cave of the Crystals within Chihuahua state's Naica Mine. This chamber is filled with selenite crystals many meters long that formed over hundreds of thousands of years in magma-heated, mineral-rich groundwater. Inside these crystals are small, fluid-filled pockets, from which researchers cultured organisms that have never been seen before. [See Photos of the Cave of the Crystals]

"What we have been finding are organisms whose closest relatives are also from extreme environments around the world," said study leader Penelope Boston, director of NASA's Astrobiology Institute. (Astrobiologists study extreme life on Earth to understand the sort of environments that might be amenable to life on other planets.)

Crystal cave

The Naica crystals were discovered by accident in 2000, according to The Naica Project, an organization dedicated to researching and preserving the cave. The formations were accessible only after the company that operated the Naica Mine pumped the groundwater out of the chamber. Even so, reaching the beauty of the Cave of the Crystals was a challenge: The 90 to 100 percent humidity and temperatures ranging from 113 to 122 degrees Fahrenheit (45 to 50 degrees Celsius) mean that humans must wear protective clothing packed with ice bags and leave the cave quickly. The recommendation, Boston told Live Science, is to stay no more than 30 minutes.

"I stayed in once for 55 minutes, which was a giant mistake," said Boston, who described the results as "life-threatening." After a half-hour in the hot crystal cave, researchers had to chug electrolyte drinks in a nearby cavern that was cooled to a refreshing 100 degrees F (38 degrees C) in order to recover. [The 7 Harshest Environments on Earth]

Today, the Naica Mine is no longer active, and water has again filled the crystal cavern. Boston and her colleagues took two trips to the mine, in 2008 and 2009, before the cave was flooded.

Microbe revival

The idea to search for microbes in the crystals arose shortly after the cave was discovered in 2000, Boston said. Paolo Forti, an emeritus professor at the University of Bologna, in Italy, alerted Boston (who was then at the New Mexico Institute of Mining and Technology) to what appeared to be microbe fossils in samples from the caves. [The 10 Strangest Places to Find Life on Earth]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When drilling into the crystals in 2009, the researchers took multiple precautions to avoid contaminating the ancient microbes. They used a sterile drill and drill bits, wore sterile gloves, and disinfected the surface of the crystals with hydrogen peroxide. They extracted fluid with sterile micropipettes. Later, the researchers created potential growth media, the nutrient gels on which bacteria grow in labs, based on their best guesses of what microbes in that environment might use for survival.

Then, the researchers put portions of the fluid from the crystal in each of the various media, to see if any of the microbes might start metabolizing. Some did.

The microbes that ended up growing were genetically distant from any known living microbes, Boston said. Based on the growth rate of the crystals, they were probably isolated in the fluid pockets for between 10,000 and 50,000 years, the researchers reported Feb. 17 at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. They are now preparing their results for publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

The results will certainly undergo scrutiny by fellow scientists, as claims for ancient microbe revivals are always controversial. However, 10,000 to 50,000 years of dormancy is a relatively conservative claim in the world of ancient microbes. In 2000, researchers claimed in the journal Nature to have grown 250-million-year-old bacteria from a salt crystal found in Carlsbad, New Mexico. There have also been claims of ancient life dating back tens or hundreds of thousands of years from salt in Death Valley, California, and from under glaciers and permafrost in the Arctic and Antarctic.

These claims are often controversial, both because of the potential for modern contamination and because salt and ice flow (very, very slowly) over geologic time, Boston said. It can be difficult, she said, to prove that the samples weren't exposed to the outside world between the time the salt and ice formed and the modern day. The Naica crystals have the advantage of being static, Boston said; they don't flow, so they're easy to date.

There is always the chance that the bacteria entered the crystals through microfractures, Boston said, which is why the team was meticulous in disinfecting the crystal surfaces and genetically analyzing the microbes that did grow. For that reason, Boston is optimistic that the microbes from the crystals will prove to be truly ancient.

"We have been pretty excruciatingly careful trying to test our ideas and look at the organisms, and then try to see if we ourselves believe what we are claiming," she said.

The nine years it has taken to get from sampling the crystals to announcing the first results is only the beginning, though, Boston said.

"The amount of work that it's going to take to really characterize that environment and its inhabitants is stupefying," she said.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.