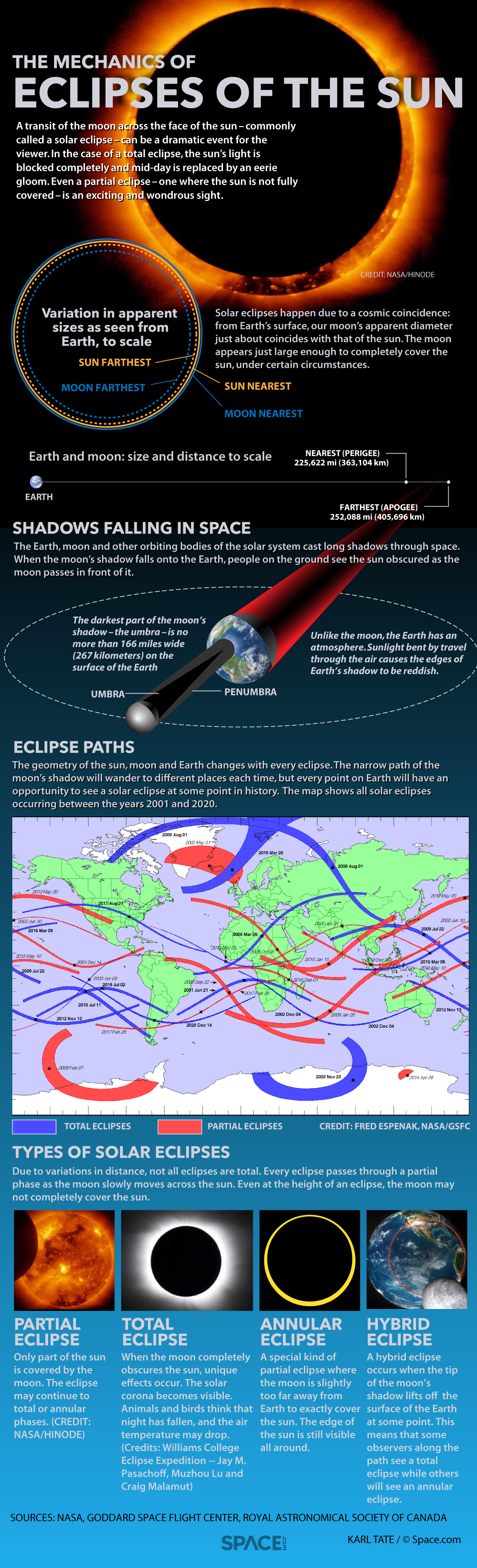

This Sunday (Feb. 26) brings the first solar eclipse of 2017. Unlike the total solar eclipse that will cross the continental United States in August, Sunday's spectacle is an annular eclipse, which means a sliver of the sun's surface will still be visible around the moon.

The moon will appear to block varying amounts of the sun depending on where you are located within the eclipse visibility zone. For those who are properly positioned along a narrow path some 8,500 miles (13,700 kilometers) long and averaging roughly 45 miles (72 km) wide, the dark disk of the moon will briefly be surrounded by a dazzling "ring of fire" as the lunar disk passes squarely in front of the sun.

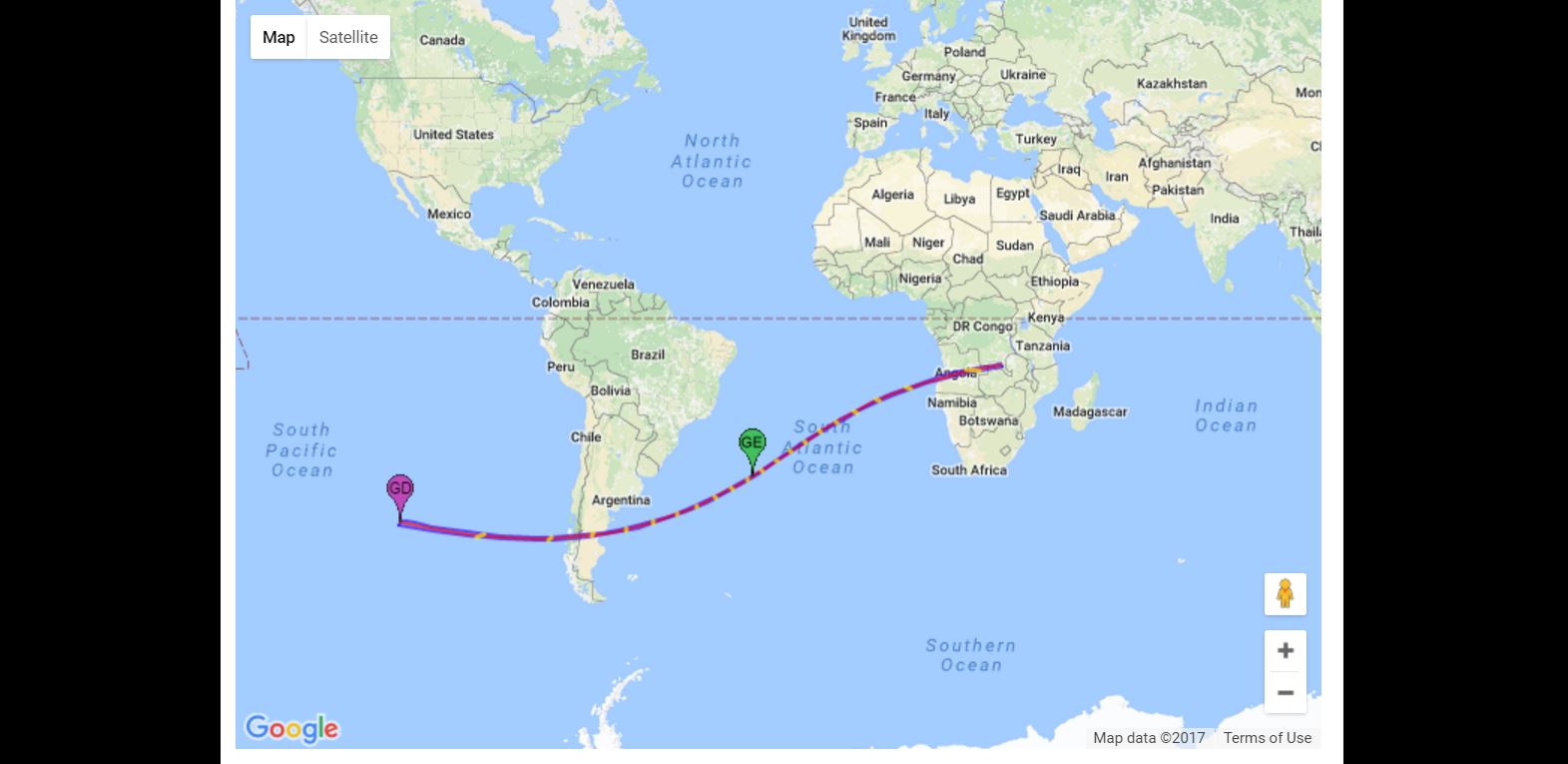

Skywatchers positioned outside this path can still enjoy a partial solar eclipse. This spectacle will be visible to more than half a billion people living across the lower two-thirds of South America as well as the western and southern portions of Africa, as well as the sparse population in about half of Antarctica. If you won't be in the area where the eclipse is visible, you can watch the Slooh Community Observatory's live webcast of the eclipse here on Space.com. [Solar Eclipses: When Is the Next One?]

From all of these regions, skywatchers who scrutinize the sun, either by safely projecting its disk through a pinhole camera or with solar viewing glasses, will be able to see the dark silhouette of the new moon passing across some portion of the sun's face.

Penny-on-nickel effect

Because the moon orbits Earth in an elliptical orbit, its distance from our planet can vary by as much as 31,000 miles (50,000 km). It is from within its dark, conical shadow (the umbra) that a total eclipse can be observed. But on Sunday, the moon will be 235,009 miles (378,210 km) from Earth — about 568 miles (914 km) too far for the tip of the umbra to reach Earth. So instead, it's the extension of this shadow tip — the so-called "negative shadow," or antumbra — that sweeps across the Earth. Because the apparent diameter of the moon under this shadow will appear ever-so-slightly smaller (less than 1 percent) compared to that of the sun, it will be unable to completely cover the sun, hence the ring of light that remains visible around the moon.

As an analogy, think of placing a penny on top of a nickel, with the penny representing the moon and the nickel representing the sun. No matter how you try, the outer edge of the nickel will always remain uncovered. The same holds true in this upcoming case involving the moon and the sun; even at the moment of greatest eclipse, a thin ring of sunlight will still remain in view. The Latin word for a ring-shaped object is "annulus," which is why the upcoming event is referred to as an "annular," or ring, eclipse of the sun.

Zones of visibility

The path of the annular eclipse will cross the South Pacific Ocean, South America, the South Atlantic Ocean and Africa. Nations that will be within the path include Chile, Argentina, Angola, Zambia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In South America, the first landfall of the moon's antumbra will occur along the southern shore of the Gulf of Corcovado. Moving inland, the track crosses the Chilean village of Puerto Aisen and the larger town of Coyhaique before moving into Argentina. The so-called ring of fire will be visible from the towns of Malaspina and Camarones, which are situated along the coastal highway that runs from Comodoro Rivadavia and Rawson. Then, the shadow will head out over the open ocean waters of the South Atlantic, with its next landfall coming about 160 minutes later in Africa.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The moment of greatest eclipse will occur midway between the continents at 1452 GMT, when the moon will cover 99.2 percent of the sun's diameter. The width of the antumbra at this spot on Earth will have shrunk to just 19 miles (31 km), and the annular, or ring, phase will last just 44 seconds.

When the shadow arrives at the west coast of Africa at Lucira, Angola, its width will have increased to 44 miles (70 km), and the duration of the ring phase will have increased to just over a minute. But at this point, the sun will be low in the western sky as the eclipse track nears its end. Continuing east, the moon's shadow will pass over the village of Cuima, south of Huambo, and then race into northwest Zambia just prior to leaving the Earth just to the west of Lubumbashi, in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, producing a fantastically unusual sunset; instead of a reddened ball, the sun will resemble a fiery hoop.

Coming soon: the "big" event

As spectacular and unusual as an annular solar eclipse is, it falls far short of the magnificence of a total solar eclipse. Indeed, even just a narrow ring of sunlight remaining will be more than enough to kill off the effect of a sudden darkening of the sky that takes place during a total solar eclipse, allowing the brighter stars and planets to pop into view. And even with more than 99 percent of the sun obscured, the remaining sunlight will be more than enough to squelch the faint light of the sun's outer atmosphere — the glorious corona — which comes into view only during a total eclipse.

But now, the good news: After Sunday, the very next solar eclipse will be less than six months away, on Aug. 21. A total solar eclipse will be visible only in the continental U.S., while a partial eclipse will be visible throughout North America. It is the first total solar eclipse to be visible from the contiguous (48) United States since 1979, and the first total eclipse in 99 years that will sweep from coast to coast across the United States. It is certain to be one of the big news stories of 2017 and will be witnessed by many millions of people.

Indeed, that midsummer eclipse will take center stage, but not until after the sun and moon put on their "one ring" performance this coming Sunday.

Editor's note: If you have an amazing photo of the eclipse you'd like to share with Space.com and our news partners for a possible story or image gallery, please send your photos to our staff at spacephotos@space.com

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Fios1 News in Rye Brook, New York.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.