Life on Earth

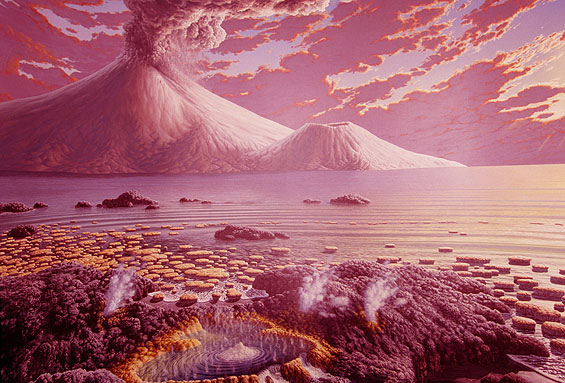

Scientists have recently unearthed fossils in Canada which are between 3.77 and 4.29 billion years old. If these fossils are truly signs of ancient life, they would be among the oldest evidence for life on Earth yet discovered. Here, an artist's depiction of what the Earth was like in one its earlier periods, the Archean.

Microbial fossils

In 2017, analysis of microbial fossils — first unearthed in western Australia in 1982 — found them to be around 3.5 billion years old. This investigation was the first to examine and describe individual, fossilized microbes, finding organic evidence in the fossils' chemical signatures and morphology.

Iron-rich rocks

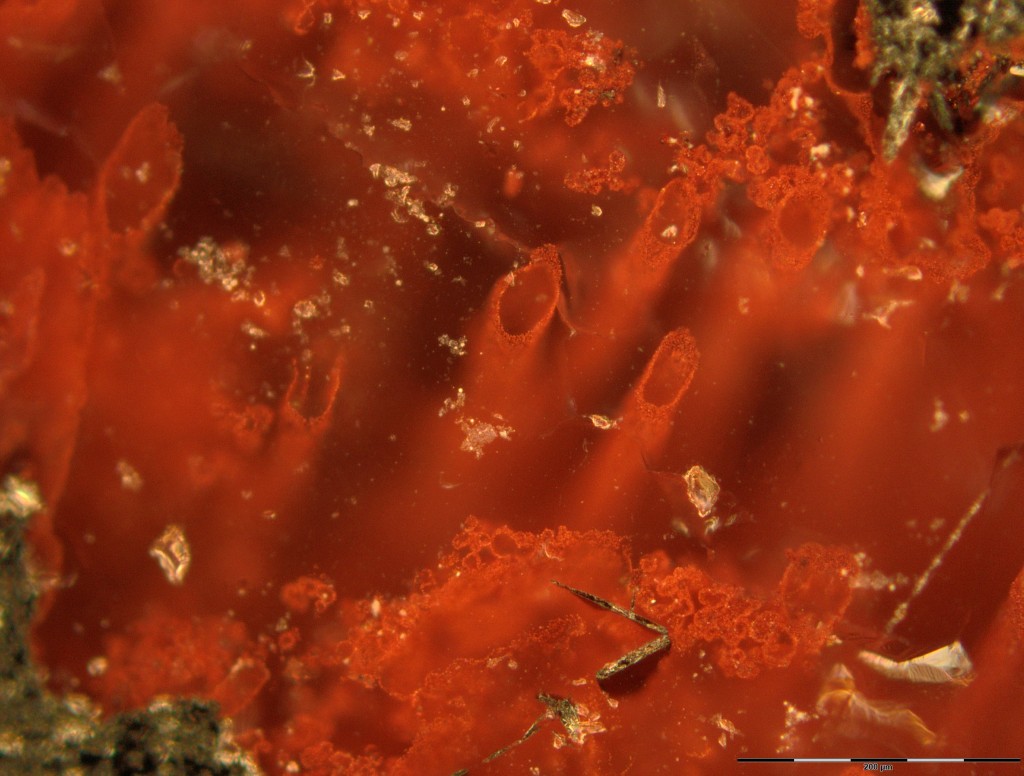

The microfossils were found in an iron-rich stretch of volcanic rock known as Nuvvuagittuq Supracrustal Belt, in Québec, Canada. This type of rock, known as jasper, is touching a dark green volcanic rock, which were possibly precipitated from hydrothermal vents deep in the seafloor.

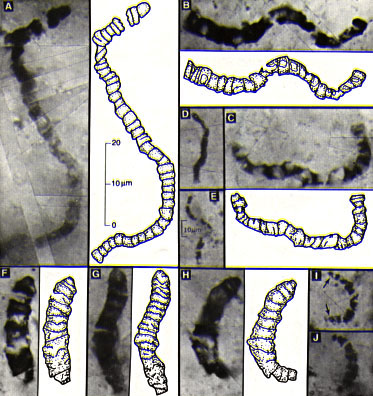

Hematite filaments

Within these fossils were tiny tubes of a mineral called hematite, a form of iron. The researchers believe these tubes are relics of an ancient form of microbial life that lived near hydrothermal vents.

Filaments and iron clumps

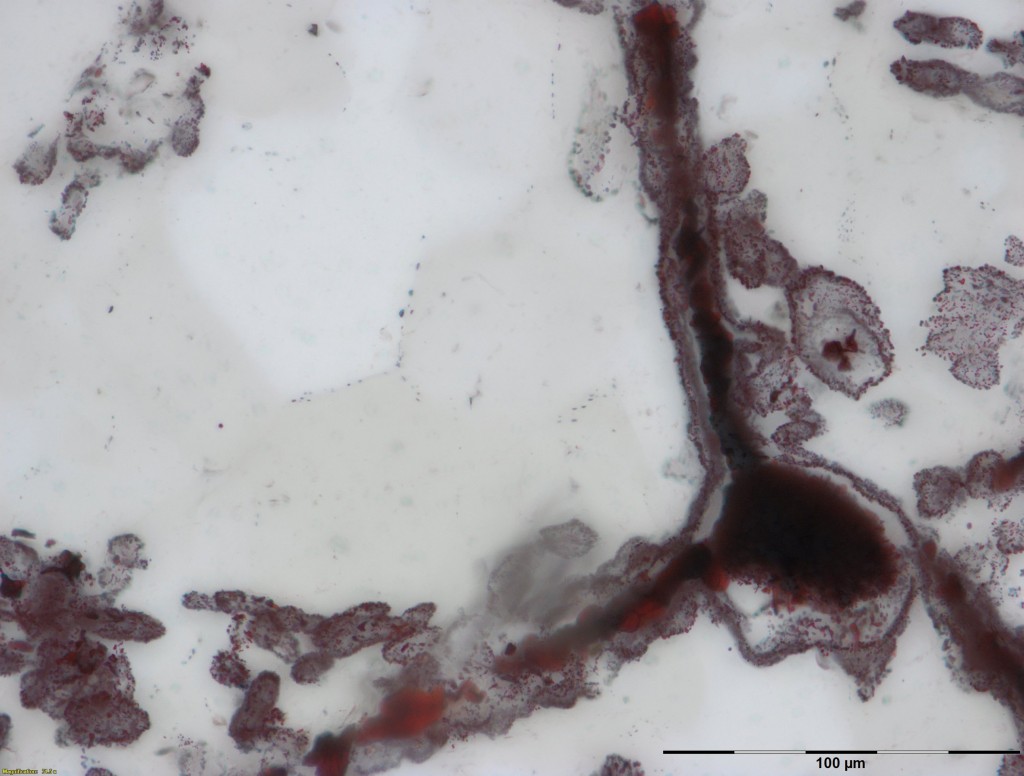

Here, a hematite filament is attached to a clump of iron. In modern hydrothermal vents, microbes are often found associated with these iron clumps.

Structure of life

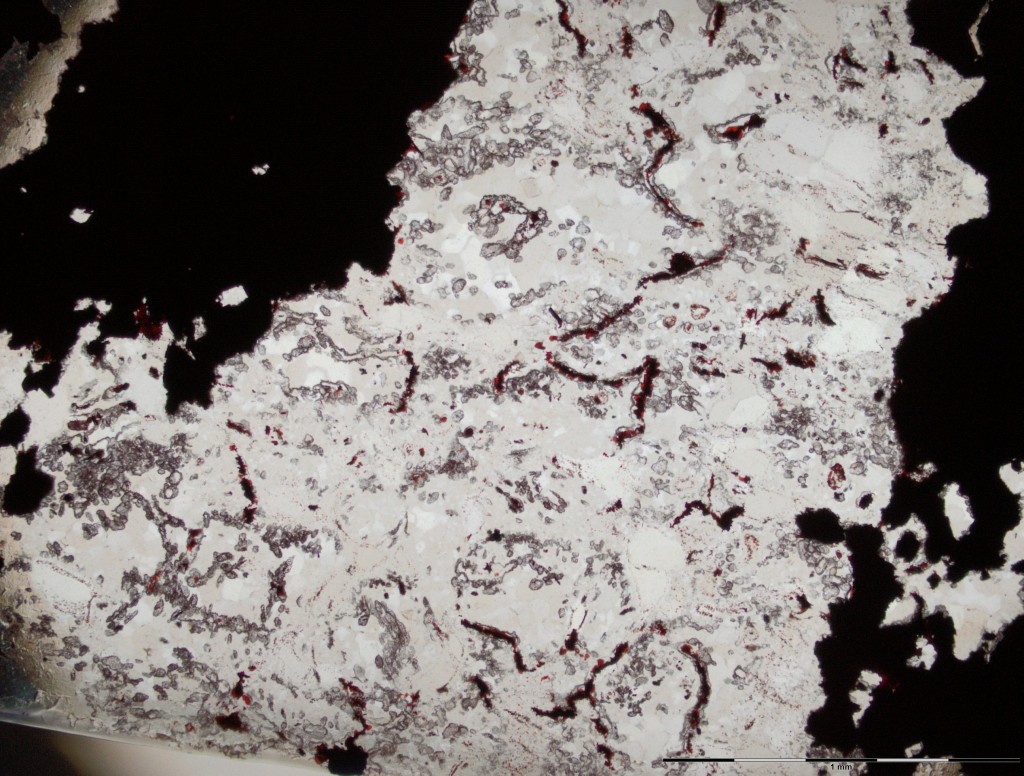

Microscopic images of the filamentous microfossils show the various layers found. The microfossils were found inside a concretion, or a hard solid accumulation of mass that often forms when organic material decays on the seafloor. The filaments (red lines) are made of hematite, and are embedded in a quartz layer and surrounded by magnetite. Hematite and magnetite both contain iron.

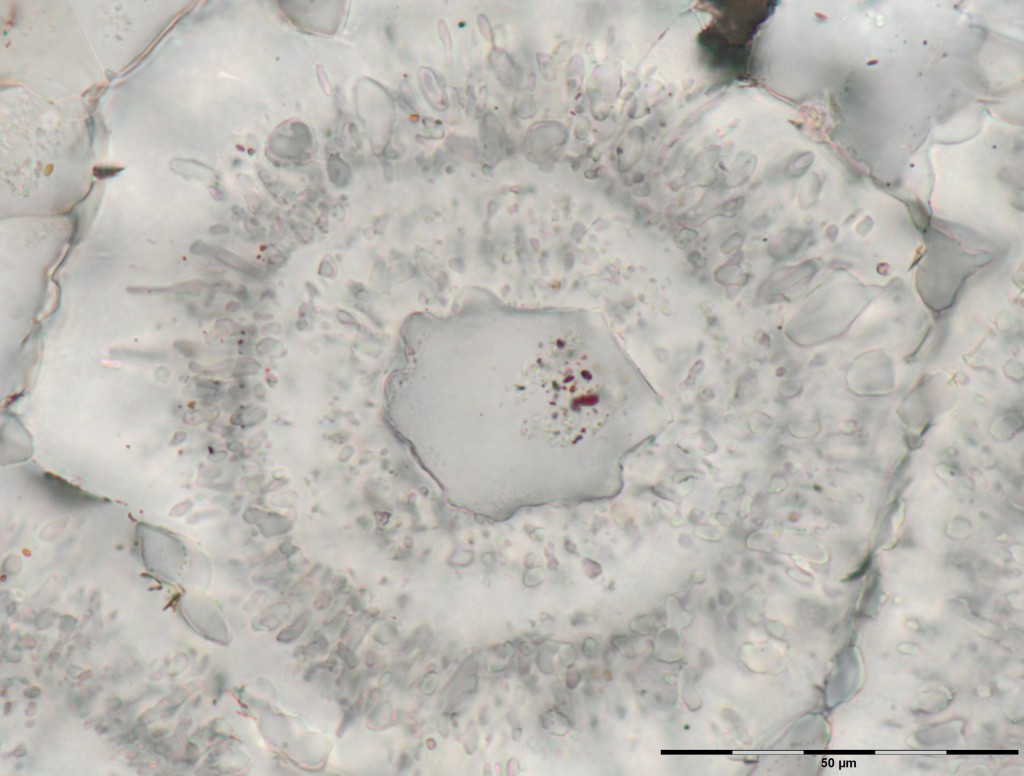

Intriguing rosette

Here, a microscopic image of a rosette made from carbonate. It contains concentric layers of quartz inclusions and a quartz core. It also has tiny inclusions of hematite, which could have formed when hydrothermal vent microbes oxidized iron as part of their metabolism.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Controversial rocks

However, claims of primordial life are always controversial. For instance, decades ago researchers discovered what they said were 3.5-billion-year-old fossils of ancient microbes in Australia in a formation known as the Apex Chert. Subsequent analysis has argued that the structures thought to be signs of life were in fact cut by hydrothermal vents without any lifeforms involved, and the status of these rocks has been hotly debated since.

Oldest life?

In August 2016, researchers discovered bizarre-cone rippling structures inside rock from Greenland that may be evidence of stromatolites, or colonies microbes, that date to 3.7-billion years ago. However, sediment structures that look like those formed by stromatolites can also be formed by other forces. What's more, the structures were found in rocks that were subject to intense underground heating, meaning a lot of forces were at play that may have erased other signs of life that might otherwise be present.

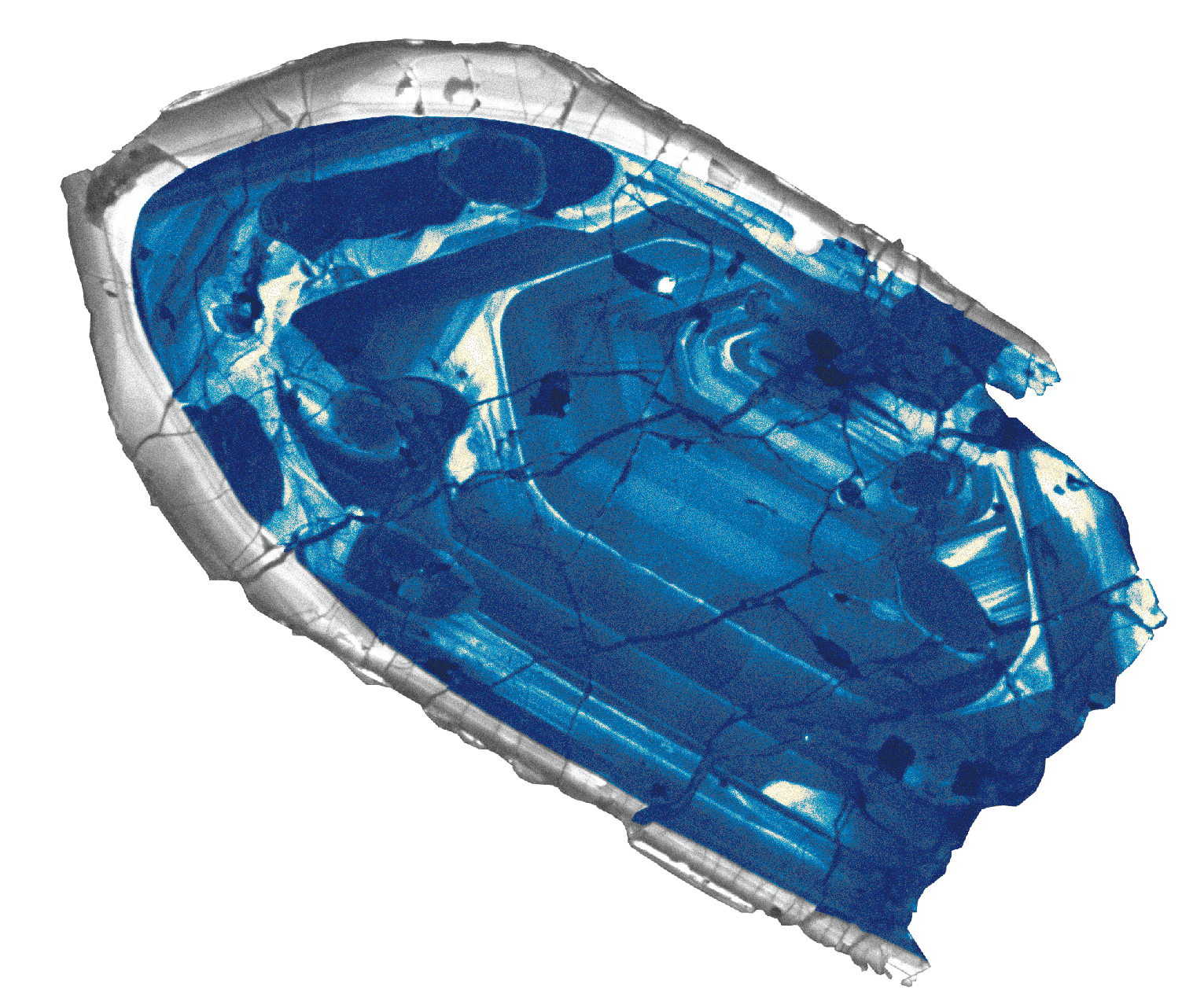

Shimmering fossils

Scientists have also claimed to have found tiny zircons with evidence of life in the Jack Hills of Australia that dates to 4.1-billion-years ago. Like the fossils found in Quebec, these have a high ratio of light-to-heavy carbon isotopes, or versions of the molecule with different weights. Because life prefers to build its chemistry around lighter versions of carbon, that can be a sign of life.

Breath of fresh air

Overall, more and more evidence suggests that Earth was a hospitable place for life earlier in its history than previously thought, though complex lifeforms took longer to emerge. Multicellular life in more complex forms likely didn't arise until the Great Oxidation Event, around 2.3 billion years ago. The rock shown here is a 2.48 billion-year-old banded iron formation from Australia that contains high concentrations of chromium, which scientists believe is evidence of a pivotal change in the Earth's atmosphere: the arrival of oxygen.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.