Photos: Renaissance Husband's Heart Buried with Wife

Church Patron

The wrapped body of Louise de Quengo, a church patron buried at the Jacobin convent in the city of Rennes in 1656. De Quengo, who was at least 65 when she died, was interred with her husband's preserved heart in a lead urn on top of her coffin. Her husband, Toussaint de Perrien, knight of Brefeillac, had died in 1649. [Read full story about the Renaissance-era burial]

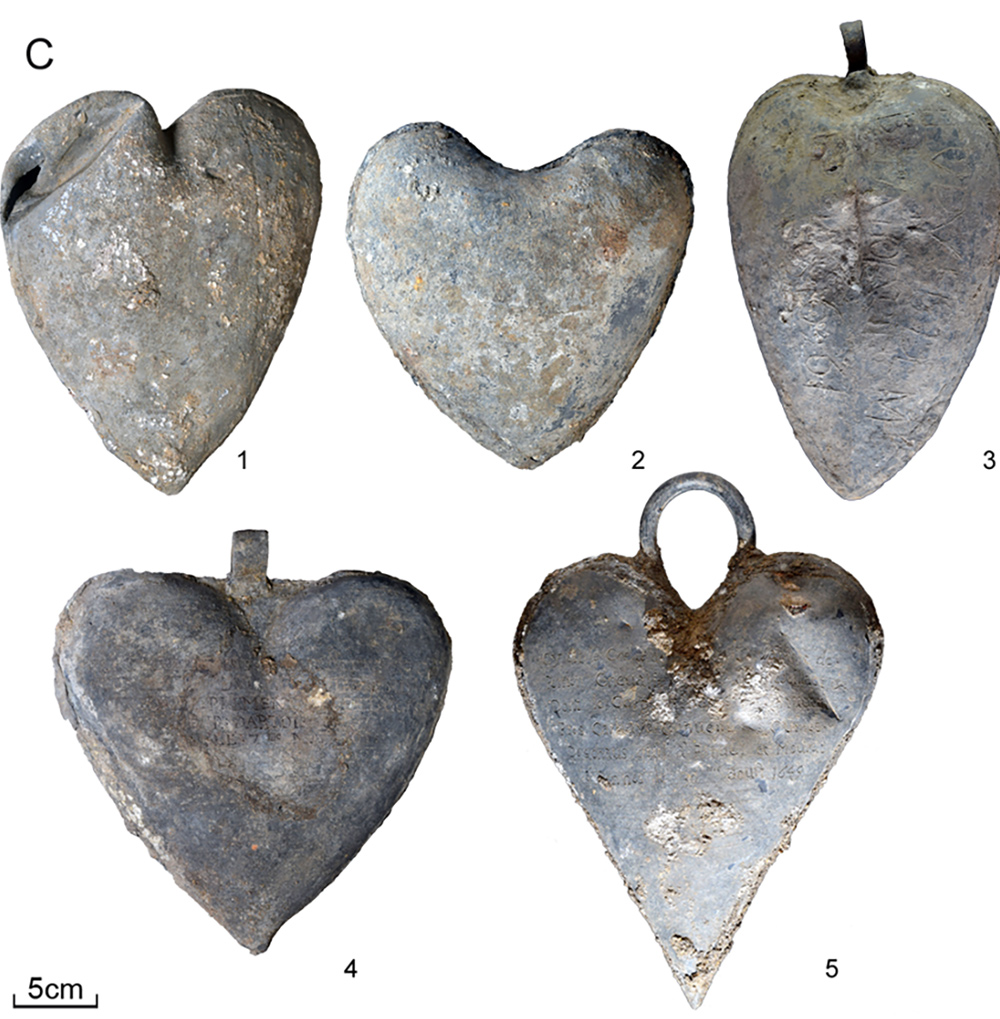

Heart to Heart

Toussaint de Perrien's heart was one of five found in lead urns at the Rennes convent. One bore no inscription. The other four, including de Perrien's, had inscribed dates ranging from between 1584 and 1655. According to the inscriptions on the lead urns, the remaining hearts belonged to Catherine de Tournemine, Monsieur d'Artois and the son of la Boessière. Nothing is known about these people but their names.

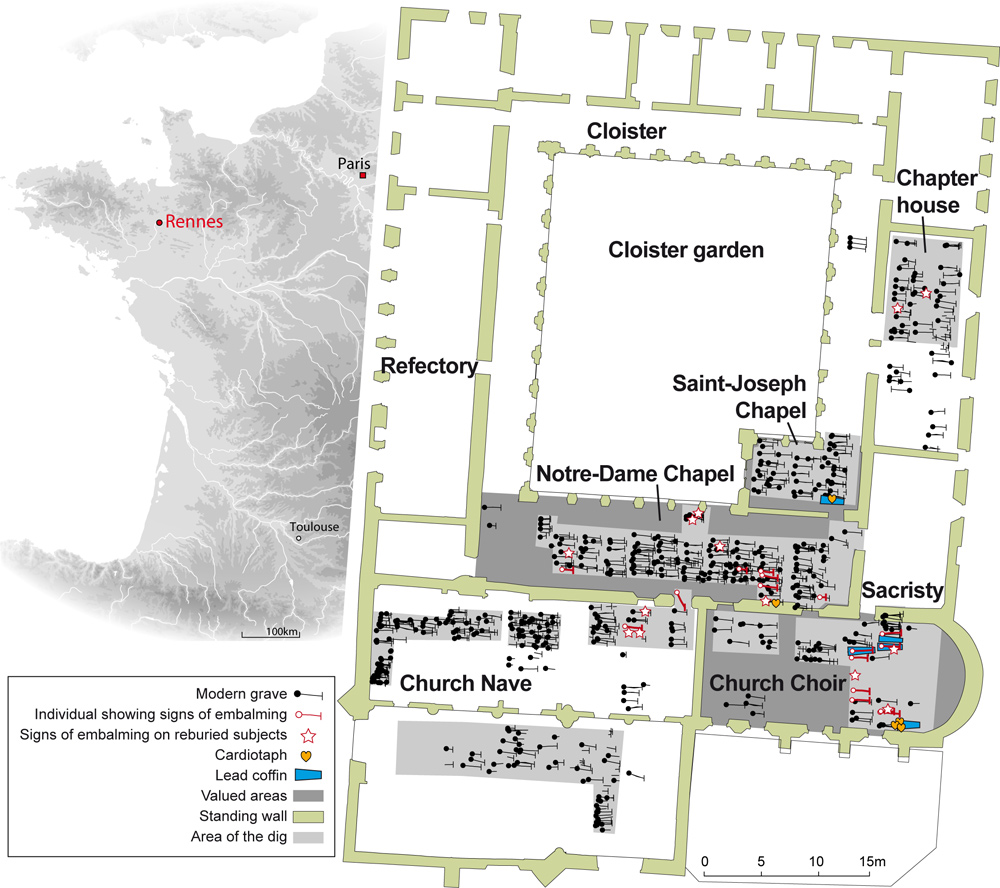

Mapping a Convent

A map of Brittany (left) showing the location of Rennes, along with a map of the city's Jacobin convent. Graves are marked with black or red lines (indicating embalming), and the locations of embalmed hearts, or cardiotaphs, are shown with yellow heart emblems. Louise de Quengo's coffin can be seen in blue in the Saint-Joseph Chapel, the color indicating that the coffin was made of lead.

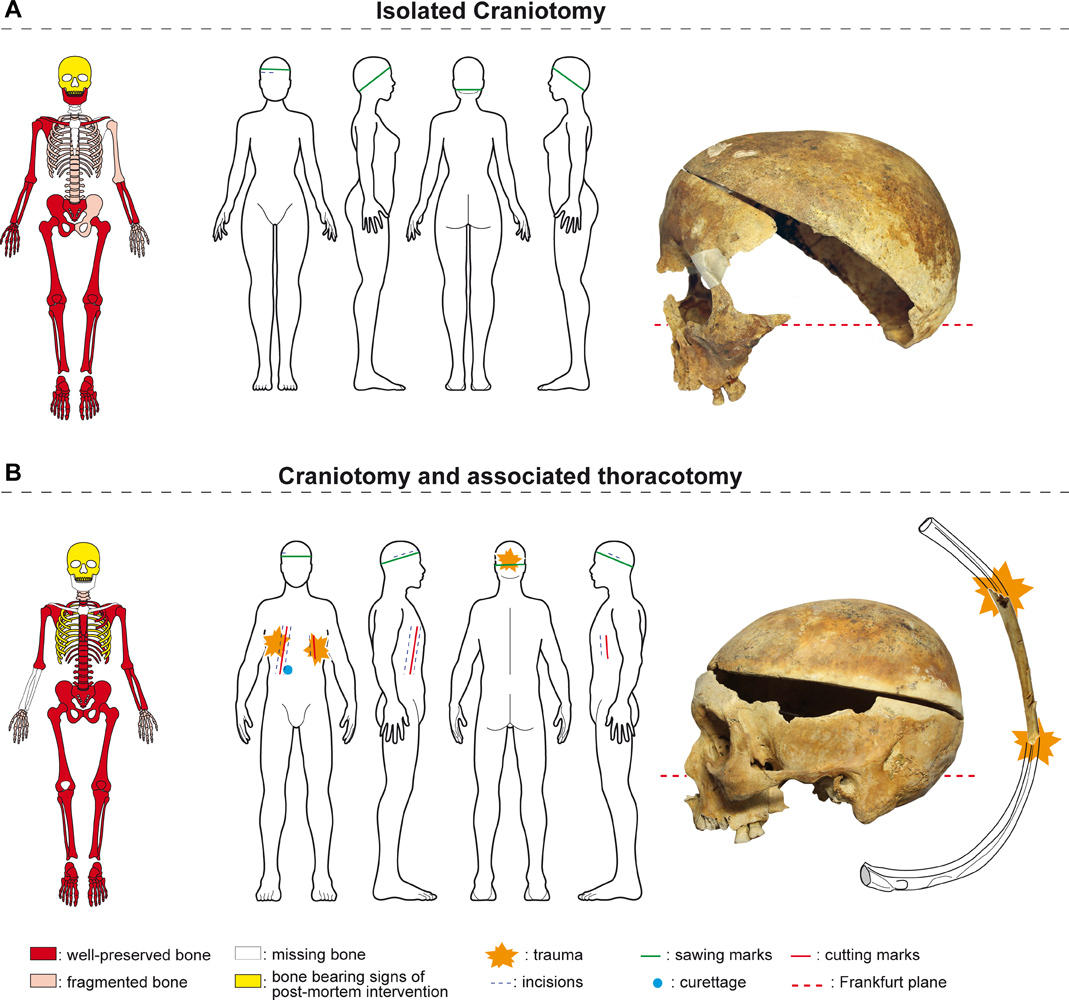

Embalmed Bodies

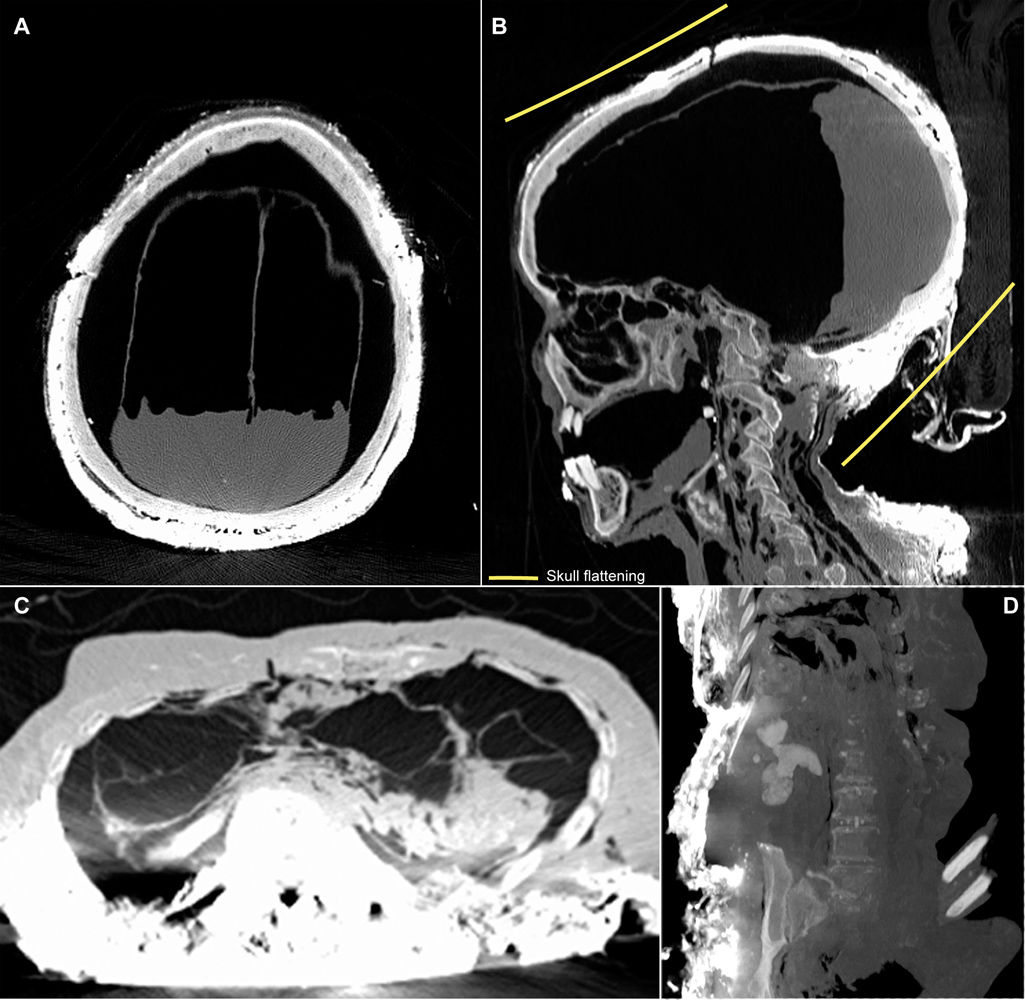

Twelve skeletons buried in the Jacobin convent cemeteries between the 16th to 18th centuries showed signs of embalming. These examples show a craniotomy, or an opening of the skull, in a female corpse (top), as well as a craniotomy and a thoracotomy in a male. The male skeleton had the skull opened as well as several incisions in the chest.

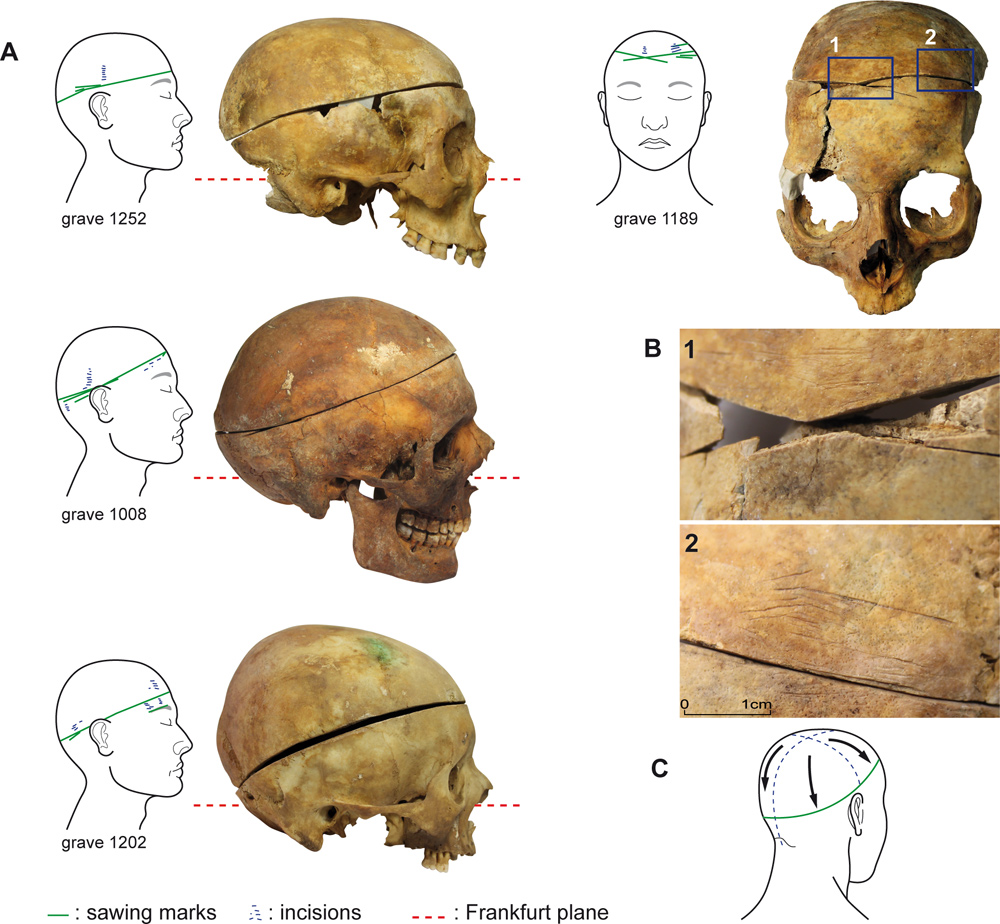

Sliced Skulls

Four skulls from the Jacobins convent that had been opened after death. It is not clear why these craniotomies were conducted, researchers wrote in the journal PLOS One. Most of the bodies with craniotomies alone were found in high-profile areas of the convent, suggesting that the brain removal may have been a ritual treatment of the body.

A Real Valentine

The cardiotaph, or heart urn, of Toussaint de Perrien, the husband of Louise de Quengo. The inscription reads, "Here lies the heart of Toussainct de Perrien, Knigh of Brefeillac, whose bodies lies near Carhaix in the Discalced Carmelite Convent, which he founded, and who died in Rennes on August 30, 1649." Splitting the heart and the body allowed church patrons like de Perrien to honor two places with their burials, and also provided couples a sentimental way to show their affection even after death.

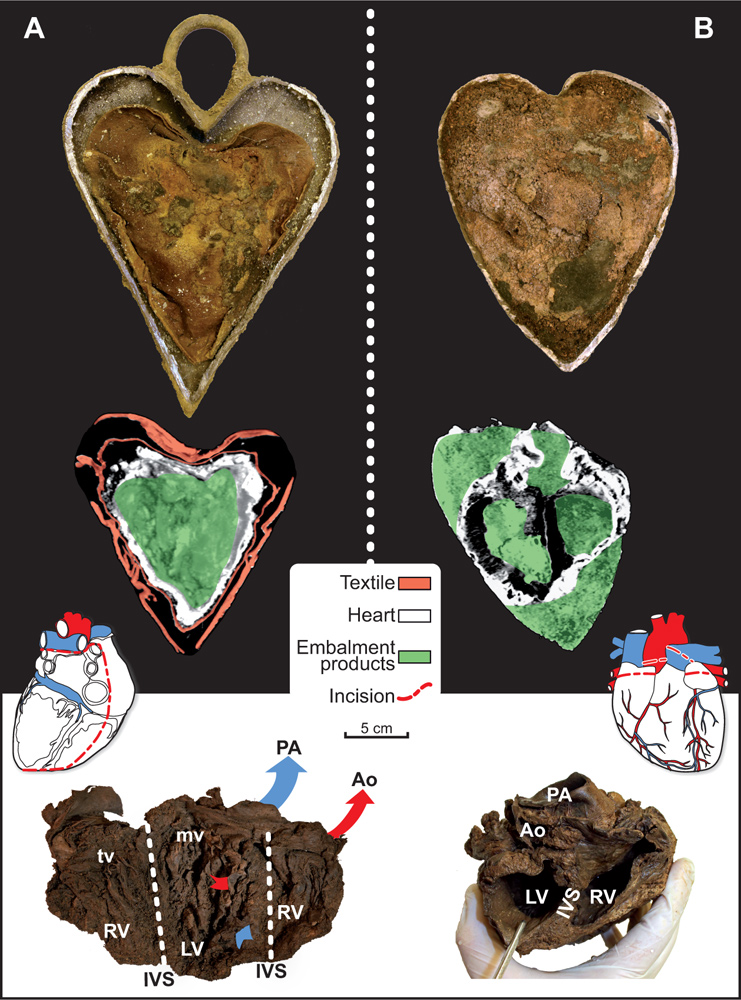

Preserving a heart

Four of the hearts found in the Rennes convent were well-preserved, even hundreds of years after burial. They had been removed from the chest with a slice of the major blood vessels. Grain or vegetable fibers were packed in and around the heart, researchers wrote in the journal PLOS One.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

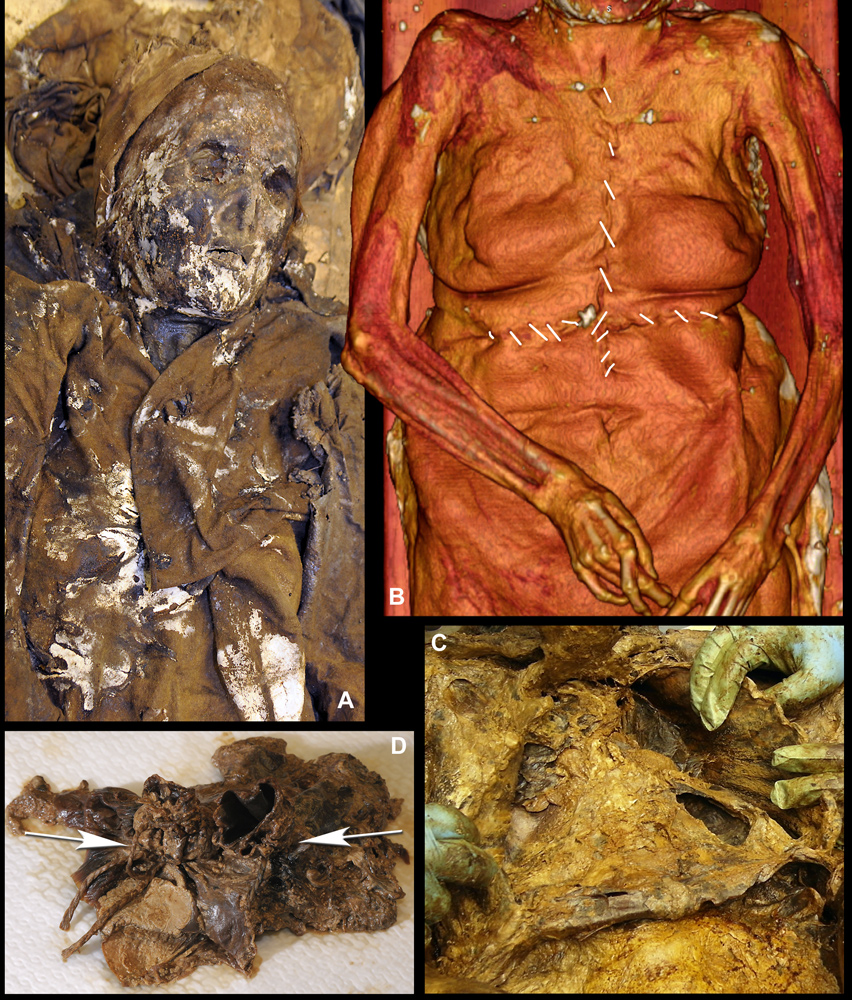

Louise de Quengo

Louise de Quengo's body had naturally mummified within her lead coffin. She was dressed as seen here, in a black cloak, a monk's wool dress, a shirt of undyed twill wool and simple leather-and- cork shoes. Here nunlike veils indicate her religious piety, and the simple clothes indicate her desire to be associated with the Jacobins, who were dedicated to the poor.

An Early Postmortem

The body of Louise de Quengo, showing the incisions made after her death. The church patron's heart was, like her husband's, removed from her chest. The rest of the organs were replaced and the chest crudely stitched together.

Hearts and Brains

Computed tomography (CT) scans of the natural mummy of Louise de Quengo. The brain is decomposed but visible (top), but the heart is missing. No one knows where de Quengo's heart was buried.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.