Neanderthals Munched on 'Aspirin' and Woolly Rhinos

Neanderthals once dined on woolly rhinoceroses and wild sheep, and even self-medicated with painkillers and antibiotics, according to a new analysis of their dental plaque.

But the diets of Neanderthals — the closest known extinct human relative, which co-existed and sometimes bred with humans before going extinct about 40,000 years ago — varied depending on where they lived.

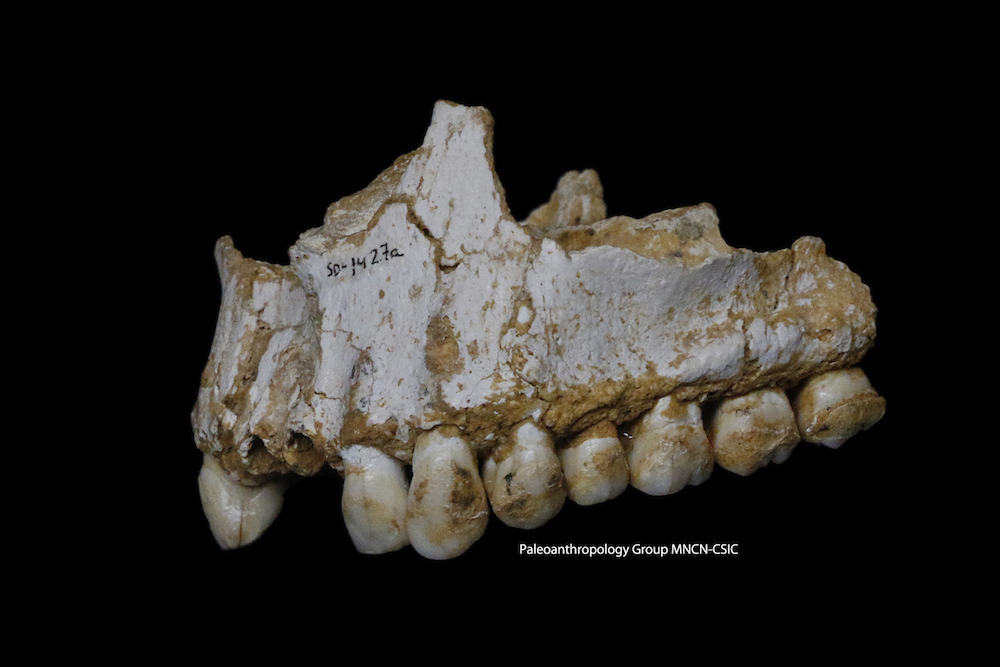

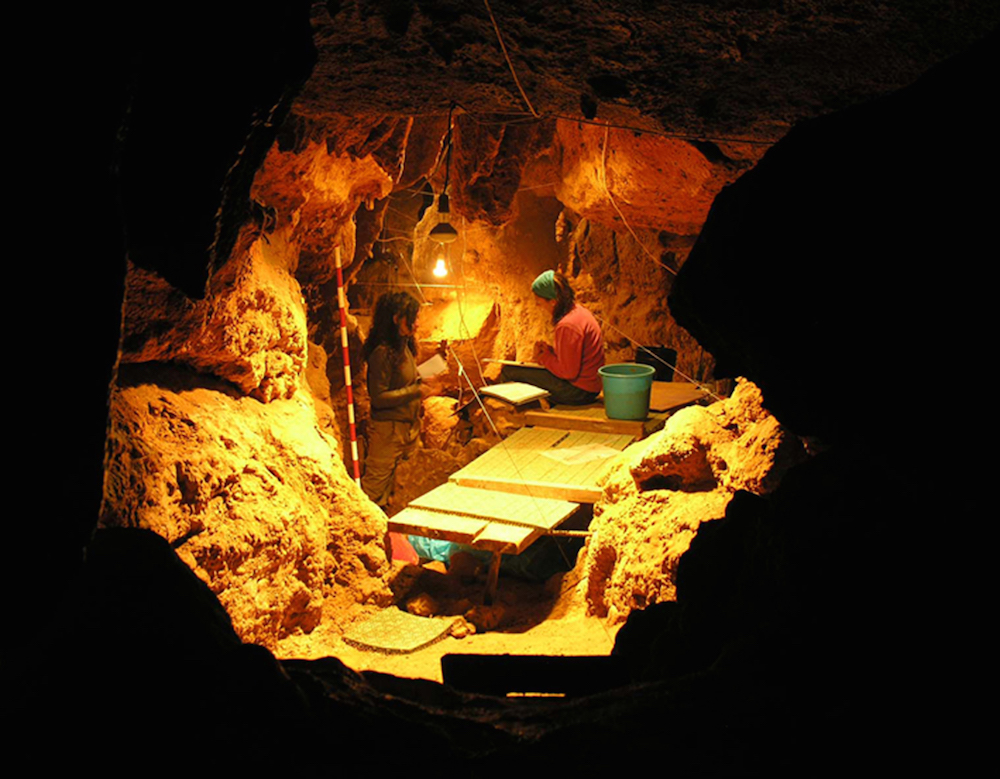

Researchers sequenced the ancient DNA of dental plaque from five Neanderthal skeletons — two from Spain's El Sidrón Cave, two from Belgium's Spy Cave and one from Italy's Breuil Cave. (However, the plaque sample from the Breuil Cave Neanderthal "failed to produce amplifiable [DNA] sequences," and one of the Spy Cave individuals had DNA plaque contamination, so the researchers excluded both from the plaque analysis, they wrote in the study.) [In Photos: New Human Ancestor Possibly Unearthed in Spanish Cave]

Dating back between 42,000 and 50,000 years, the plaque is the oldest dental plaque on record to be genetically examined. The analysis revealed that some, but not all, Neanderthals were meat lovers.

The Neanderthal at Spy Cave dined heavily on meat, including the woolly rhinoceros and wild sheep — an unsurprising discovery, given that the bones of woolly rhinoceroses, reindeer, mammoths and horses were found within Spy Cave, and wild sheep lived throughout Europe during that time period, the researchers said. This Neanderthal also ate edible gray shag mushrooms, the analysis showed.

In contrast, the Neanderthals from the cave in El Sidrón were largely vegetarian. Their dental calculus (hardened plaque) indicated that they ate edible mushrooms, pine nuts, moss and poplar, likely foraged from the surrounding forest, the researchers said. Moreover, the calculus also showed evidence of fungal pathogens, suggesting that the El Sidrón Neanderthals might have munched on mold, the researchers said.

The findings show "quite different lifestyles" between the El Sidrón and Spy Cave groups, study senior researcher Alan Cooper, director of the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA at The University of Adelaide in Australia, said in a statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Self-medication

One of the Neanderthals at El Sidrón wasn't in good health: The hominin had a dental abscess (a painful tooth infection) and a diarrhea-causing intestinal parasite. However, the individual was self-medicating, the dental plaque analysis indicated.

The individual's plaque showed evidence of poplar — a tree that contains the natural painkiller salicylic acid, aspirin's active ingredient — as well as DNA sequences of a natural antibiotic found in mold, the researchers found.

"Apparently, Neanderthals possessed a good knowledge of medicinal plants and their various anti-inflammatory and pain-relieving properties, and seem to be self-medicating," Cooper said. "The use of antibiotics would be very surprising, as this is more than 40,000 years before we developed penicillin. Certainly our findings contrast markedly with the rather simplistic view of our ancient relatives in popular imagination."

Mouth bacteria

The scientists also examined the Neanderthals' mouth bacteria, known as the oral microbiome, and compared the results with oral bacteria from other groups. The oral microbiome of the El Sidrón Neanderthals was more similar to that of chimpanzees and foraging human ancestors from Africa, while the Spy Cave Neanderthals' mouth bacteria looked more like those from early hunters and gatherers and modern humans, the researchers found.

"Not only can we now access direct evidence of what our ancestors were eating, but differences in diet and lifestyle also seem to be reflected in the commensal bacteria that lived in the mouths of both Neanderthals and modern humans," study co-author Keith Dobney, a professor of human paleoecology at the University of Liverpool in the United Kingdom. [Microbiome: 5 Surprising Facts About the Microbes Within Us]

In addition, one of the El Sidrón individuals had the near-complete genome of Methanobrevibacter oralis, an oral bacterium that causes cavities and gum disease. At 48,000 years old, the specimen is the oldest draft microbial genome on record, the researchers said.

M. oralis also infects modern humans, and its presence in the Neanderthal suggests that the two hominins were swapping pathogens as recently as 180,000 years ago, long after Neanderthals and humans diverged as separate species, the researchers said.

The study was published online today (March 8) in the journal Nature.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Why is yawning contagious?

Scientific consensus shows race is a human invention, not biological reality