Jaw-Dropping Vision Helps Tiny Flies Snag Prey in Under a Second

Just because something is tiny doesn't mean it isn't fierce. For the mosquito-sized robber fly, the key to its deadly hunting prowess is all in the eyes.

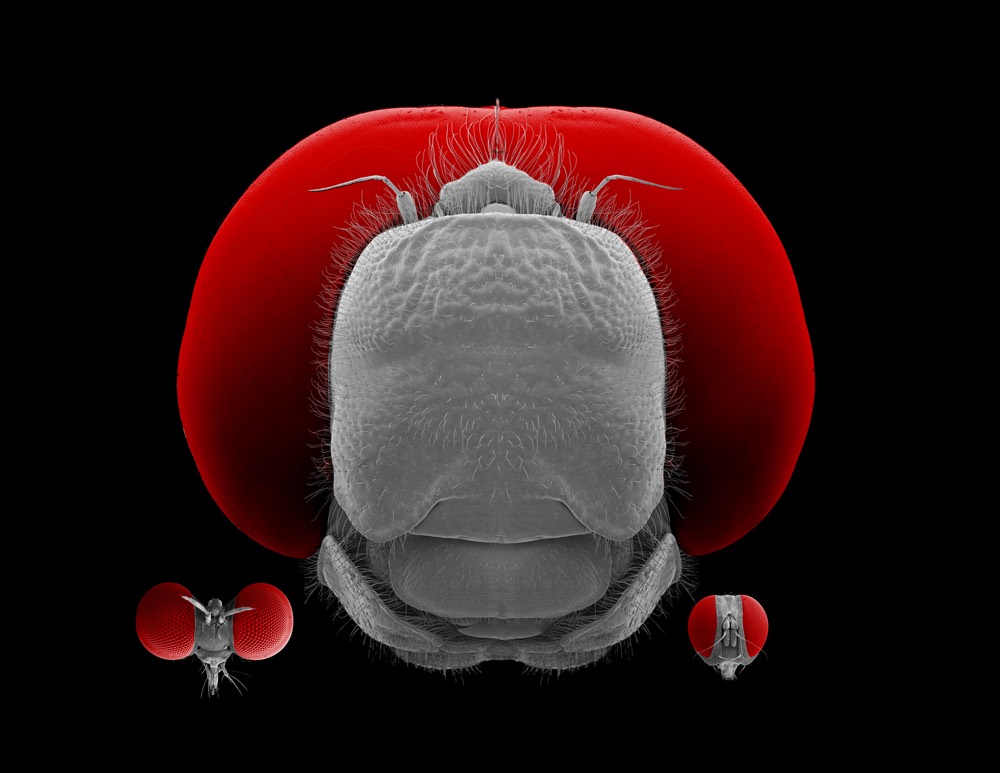

Robber flies, of the genus Holcocephala, are just about 6 millimeters in length, but they boast a subset of eye lenses as big as the lenses of dragonflies. (Robber flies are 10 times smaller than dragonflies.) These specialized lenses give robber flies vision nearly as sharp as dragonflies, which have the best-known vision of any insect.

"We knew that these flies likely had an improved vision compared to other true flies, but we never imagined that they would give dragonflies, which are 10 times larger, a run for their money with regards to spatial resolution of the retina," Paloma Gonzalez-Bellido, a neuroscientist at the University of Cambridge, said in a statement. [See Images of the Amazing Robber Fly Eyes]

Lens size matters

Dragonflies owe their sharp vision to large lenses within their compound eyes. Robber flies hunt in the same way as dragonflies do — by intercepting prey midair — but their small size means they can't carry the giant compound eyes that dragonflies have.

In new research published today (March 9) in the journal Current Biology, Gonzalez-Bellido and her colleagues found that robber flies get around this size problem by concentrating large lenses where it matters: right in the center of the eye. The flies have lenses ranging from 20 microns to 78 microns in diameter, with 78 microns about the width of a human hair, matching the lens size of dragonflies. These largest lenses are clustered together and paired with small light-receptor cells that are set back farther from the lens than typically seen.

"The effect of this is like zooming in on a camera lens," study co-author Sam Fabian of Cambridge said in a video describing the research. "By extending the focal length, the sensor at the bottom samples a smaller region of visual space."

For the flies, this translates to an effect not unlike peering through a pair of binoculars. The picture in the center of the visual field is sharp and clear, but there isn't much peripheral vision to speak of.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A deadly trajectory

That's fine for the flies, which use this sharp vision to capture prey as far as 1.6 feet (0.5 meters) away. To figure out how the flies manage these aerial feats, the researchers strung tiny silver beads on a fishing line to mimic prey and then used high-speed video to film the flies' blink-of-an-eye attacks. They used the video to reconstruct the flies' trajectory and found that the insects make rapid in-air adjustments to ensure that their angle of approach to the prey stays constant. This puts the fly on an intercept course. [Vision Quiz: What Can Animals See?]

"If you think of this as though you're driving along the motorway and a car is coming down the slip [feeder] road, then if the relative angle between you and this car remains constant, you will collide," Fabian said in a statement.

When the flies take flight for prey, they begin by accelerating dramatically until they're about 12 inches (30 centimeters) from their target. They then "lock on" and slow their rate of attack, a move that probably allows them more accuracy when they hit their unsuspecting prey.

The researchers say their findings could have technological applications, particularly in the development of flying drones.

"The problem with drones is often one of the battery power necessary for accurate image processing," Gonzalez-Bellido said in a statement. "The processing power is a huge drain on resources. But as is often the case, we can take lessons from the natural world to minimize the power requirements. This, combined with the robber fly's remarkable hunting ability, could help in the design of drones designed to take down illegal drones near airports, for example."

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.