Why Itchiness Is Contagious

Mice, just like humans and monkeys, will start itching if they see a compatriot scratching itself, a new study finds.

The finding is the first evidence that "socially contagious itching" exists in rodents, the researchers said. Moreover, the researchers' neural analysis revealed that socially contagious itching is hardwired into the mouse brain.

"The mice got itchy when the other mice scratched [themselves]," said study senior researcher Zhoufeng Chen, the director at the Center for the Study of Itch at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. "Just like a human being." [Itchiness Is ‘Socially Contagious’ Among Mice | Video]

In humans, even the mention of lice can make a person feel itchy, the scientists said. Rhesus macaque monkeys also tend to start scratching themselves when they see other monkeys, or even videos of monkeys, scratching in front of them, according to a 2013 study in the journal Acta Dermato Venereologica.

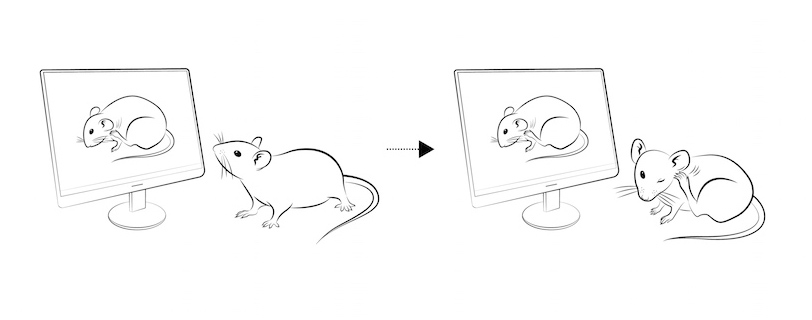

To investigate whether mice had this behavior, Chen and his colleagues put mice within view of mice that had a condition that made them itch chronically. They also put mice in front of a silent video of a mouse with an itch. In each case, the observer-mice started scratching, Chen said.

Brainy investigation

When the mice "caught" an itch, brain scans of the rodents showed increased activity in a structure called the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), which controls when animals fall asleep and wake up, the researchers said.

As the mice watched their furry "colleagues" scratch, the cells in the SCN released a chemical known as gastrin-releasing peptide, or GRP. Chen and his colleagues identified GRP as a key transmitter of itch signaling between the skin and the spinal cord in a 2007 study published in the journal Nature.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But GRP may affect only "social" itching ― it makes a mouse act as if it's seeing another mouse scratch. When the team used techniques to block GRP, as well as the receptor that it binds to, the mice did not scratch themselves when they saw other mice scratching, the researchers found. But these mice were still capable of feeling itchy — they scratched when they were injected with histamine, an itch-inducing substance, the researchers said. [9 Myths About Seasonal Allergies]

Interestingly, GRP may trigger social itching all by itself. When the researchers injected extra GRP into the rodents' SCNs, the mice scratched vigorously for an hour, even when they didn't see another mouse itching, the researchers wrote in the study.

The findings may help scientists understand brain circuits that control socially contagious behaviors, they said.

It's not entirely clear why some animals have socially contagious itching. However, it could be a protective mechanism, Chen said.

"It's possible that when a lot of mice are scratching, maybe it warns other mice that this is a place that has a lot of insects, and you'd better start scratching before it is too late," Chen said.

It's also a mystery why many animals — including humans, monkeys, wolves, dogs and even parakeets — engage in another socially contagious behavior: yawning. But researchers have found one clue: Social yawning is more likely to happen among friends and family than it is strangers, suggesting that social yawning is tied to empathy, Live Science previously reported. In contrast, socially contagious itching is not tied to empathy, the researchers said.

The new study will be published online today (March 9) in the journal Science.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.