Parts of Earth's Original Crust Exist Today in Canada

Rocks from the eastern shore of the Hudson Bay in Canada contain elements of some of Earth's earliest crust, new research finds.

The rocks themselves are granites that are 2.7 billion years old, but they still hold the chemical signals of the precursor rocks that were melted and recycled to form the rocks that exist today. The new study, published online today (March 17) in the journal Science, finds that these precursors formed around 4.3 billion years ago.

The Earth is 4.6 billion years old, and the astronomical impact that formed the moon took place about 4.5 billion years ago. That makes the precursor rocks to the Canadian granites among the earliest crust after the moon-forming impact, said study leader Jonathan O'Neil, a geoscientist at the University of Ottawa in Canada. [Photo Timeline: How the Earth Formed]

Hadean history

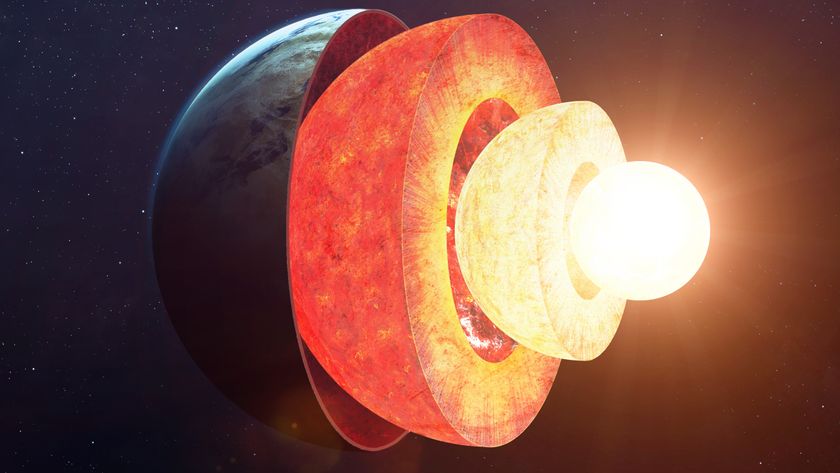

The new research is an attempt to peek back into the Hadean eon, a mysterious and rather molten phase of Earth history. The Hadean begins with Earth's formation and ends about 4 billion years ago, and very few geological remnants of this era remain. Most rocks from the Hadean were long ago recycled back into the planet's mantle.

"Rocks that are 3.6 [billion] to 3.8 billion years old or older, we can count them on the fingers of our hand, basically," O'Neil told Live Science. "We have a very limited amount of rock sample to understand the first billion years of Earth history."

The granites found north of Canada's Hudson Bay don't date to the Hadean, but they do butt up against the Nuvvuagittuq greenstone belt, a formation thought to contain the oldest known rocks on Earth, between 3.8 billion and 2.48 billion years old. (The only older geological material are small mineral grains called zircons from Australia's Jack Hills, but the original rocks that held those grains have long since weathered away.)

Some scientists think that both the Jack Hills zircons and the Nuvvuaguittuq greenstone belt contain traces of the earliest life on the planet, though those findings are controversial.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A geological family tree

O'Neil and his co-author, Richard Carlson of the Carnegie Institution for Science, were interested in the 2.7-billion-year-old granites because they knew that rocks of that sort had to be formed by a "parent" rock that had been buried and partially melted before reforming. The question was, how old was that parent rock?

To find out, the researchers turned to samarium-neodymium dating, a method that uses ratios of different variations of those two rare-earth elements to determine age. One molecular variation, or isotope, of samarium, samarium-146, no longer exists on Earth: It all underwent radioactive decay within the first 500 million years of the planet's history, O'Neil said.

Samarium-146 decays into neodymium-142, so any rock that formed after the first 500 million years of Earth's history holds the same ratio of neodymium-142 to other neodymium isotopes. Any rock that shows variation in this neodymium ratio must have formed in the first 500 million years of Earth history, the researchers said.

It was just that sort of variation that scientists found in the Hudson Bay rocks — a deficit in the neodymium-142 to neodymium-144 ratio compared with modern rocks.

"It means their parent rock had to be very old," O'Neil said. The researchers also found that the parent rock was likely basaltic oceanic crust rather than dry land.

The researchers estimate that the parent rock was 1.5 billion years older than the modern granites that survive today. That's interesting not just because the parent rock was some of the earliest crust on Earth, O'Neil said, but because the parent rock stuck around for so long before it was recycled. Today's oceanic crust persists at the surface for only about 200 million years before being pushed back into the mantle and partially melted, O'Neil said. The parent rock of the Hudson Bay granites stayed at the surface for more than a billion years before being recycled, five times as long as today's oceanic crust survives.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular