11 Ways Your Beloved Pet May Make You Sick

Introduction

For many people, pets are part of the family — owners share their beds, food and even tech gadgets with their furry companions. But just like other members of your family, pets can also give you their germs.

Although it's rare for people to catch illnesses from pets, there are a number of diseases that can spread from animals to people, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. To protect yourself from such diseases, the CDC recommends washing your hands after contact with your pet, or with their food or stool. You should also make sure your pet has regular veterinary care, which can help them stay healthy, the CDC says.

Here are 11 diseases or pathogens you could potentially catch from your pet.

The flu

Cats can become infected with flu viruses, including bird flu viruses. Little is known about the risk of humans catching flu viruses from cats; however, in rare cases, people may catch the flu from cats.

In December 2016, a New York City animal shelter reported an outbreak of bird flu (with a strain called H7N2) among the shelter's cats. During this outbreak, one person became infected with the H7N2 flu virus after prolonged, unprotected exposure to the sick cats, the CDC said. The person had a relatively mild illness, and recovered, the agency said.

Overall, the risk of catching the flu from Fluffy appears to be low, the CDC says.

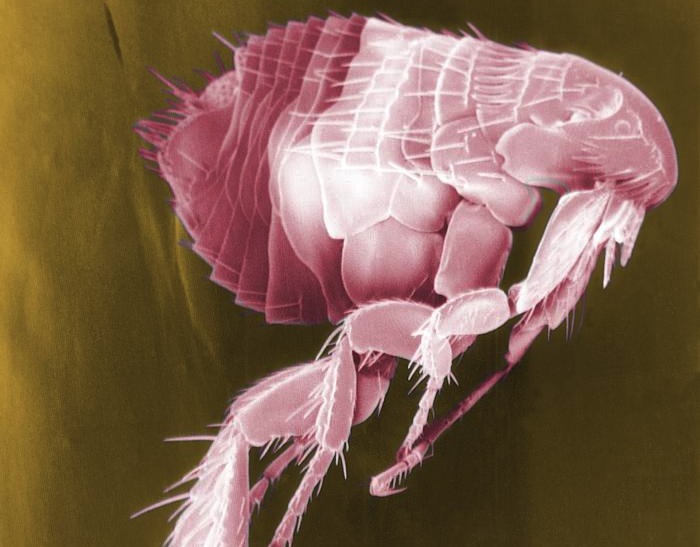

The plague

Both dogs and cats can catch the plague, the age-old disease that's caused by bacteria called Yersinia pestis. However, cats are more susceptible to the infection than dogs, the CDC says.

People can catch the plague if they are bitten or scratched by an infected pet. In some cases, people can get the plague by breathing in respiratory droplets from their pet that contain the bacteria, according to the agency's website.

Still, catching the plague from cats is not common. From 1977 to 1998, 23 people living in the western United States became infected with the plague after exposure to infected cats, according to a 2000 study published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases. That's about 8 percent of the nearly 300 plague cases that occurred in the U.S. during that time, the study said.

Pets can also spread the plague to people indirectly, because their fleas can pick up the bacteria when they feed on the animals, and spread the bacteria to people through flea bites, according to the CDC.

Salmonella

Some popular pets can spread Salmonella bacteria to people. Turtles pose a high risk of spreading Salmonella, the CDC says.

This type of bacteria occurs naturally in turtles, and people can catch the disease by handling turtles or touching the tanks or cages where pet turtles live and roam.

From 2011 to 2013, there were eight Salmonella outbreaks linked to handling tiny pet turtles (less than 4 inches long) that reached multiple states. These outbreaks sickened a total of 473 people in 41 states, the CDC said.

All turtles can carry Salmonella, but those less than 4 inches long are at especially high risk of harboring the bacteria, the CDC said. For this reason, the sale of turtles smaller than 4 inches has been banned in the United States since 1975.

Infection with Salmonella causes salmonellosis, a diarrheal illness that usually lasts about a week. But in some cases, people with salmonellosis develop a severe illness and need to be hospitalized, the CDC says.

Rabies

Rabies is a deadly viral disease that affects the central nervous system, and is spread through the bite of an infected animal.

Before the 1960s, most animal cases of rabies were seen in domestic animals, including pets, according to the CDC. But thanks to rabies vaccines for pets, domestic dogs have been eliminated as a reservoir for the rabies virus, the CDC says. Today, more than 90 percent of animal rabies cases are seen in wildlife.

However, the CDC still gets reports of about 80 to 100 dogs and more than 300 cats each year that are infected with rabies. The cases usually occur in pets that were bitten by a wild, rabid animal, and were not vaccinated against the disease. There are typically one to three cases of rabies in people reported in the United States each year, the CDC says.

People can prevent rabies by making sure their pets are vaccinated against the disease. Rabies vaccines are available for dogs, cats and ferrets, according to the CDC.

Hantavirus

Hantaviruses are a group of viruses that typically infect rodents, according to the CDC. Infected rodents can shed the virus in their urine, droppings and saliva, and tiny droplets containing virus particles can get into the air if the animals' nest is stirred up, the CDC said. Humans typically become infected when they breathe in air contaminated with the virus.

Until recently, pet rodents sold in the United States were not known to carry the Hantavirus, and the virus was seen only in wild rodents. But in January 2017, eight people in Wisconsin and Illinois became infected with Seoul virus, which belongs to the Hantavirus family, while they were working in facilities breeding pet rats. All eight recovered. Five of them had not even shown any symptoms; they simply tested positive for the infection during the investigation that the CDC began once the cases of the sick people were reported. The CDC later found five more human cases of Seoul virus tied to this outbreak, and the investigation is still ongoing.

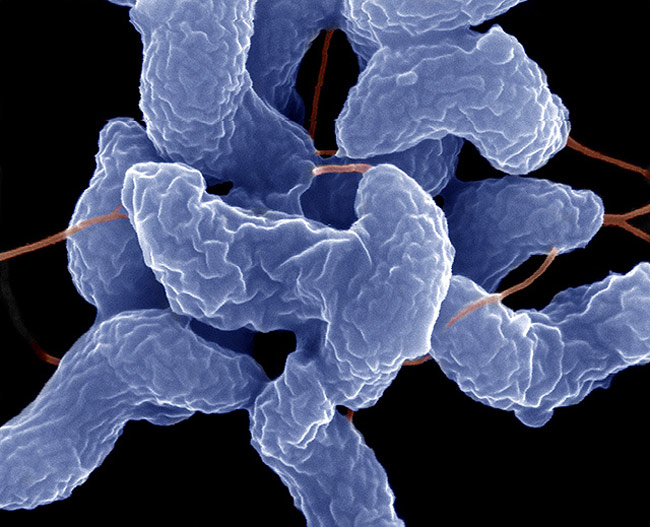

Campylobacteriosis

Campylobacteriosis is a diarrheal illness caused by the bacteria Campylobacter, which typically lives in the intestinal tract of warm-blooded animals, such as chickens, according to the World Health Organization. Humans typically become infected with Campylobacter when they eat raw or undercooked poultry.

But Campylobacter can also infect cats and dog, and these pets can, in turn, pass the bacteria to people. Owners may become infected if they have contact with the stool of an infected dog or cat, although pets carrying Campylobacter may not show signs of illness, the CDC says. People should always wash their hands with soap if they have contact with pet feces, the agency says.

Toxoplasma gondii

Cats are the main hosts for a parasite called Toxoplasma gondii. People can become infected with this parasite through contact with cat feces, which might happen when cleaning a cat's litter box, the CDC said. Most people infected with the parasite do not show any symptoms. But in severe cases, the parasite can cause damage to the brain, eyes and other organs, the CDC said. Severe infections are more likely in people who have weakened immune systems, such as those who are taking drugs to suppress their immune system.

Toxoplasma gondii can also pass from mother to child during pregnancy, and a small percentage of infected infants have serious eye or brain damage at birth. For this reason, the CDC recommends that pregnant women avoid changing cat litter.

Some studies have linked infection with Toxoplasma gondii to the development of schizophrenia and symptoms of psychosis, such as hallucinations. However, a recent study found that owning a cat in childhood does not increase the risk of experiencing psychotic symptoms later in life.

Capnocytophaga

The bacteria called Capnocytophaga lives in the mouths of dogs and cats. In rare cases, people can become infected with Capnocytophaga through bites, scratches or even licks from an animal. Most people who have contact with dogs and cats won't get sick, but people with weakened immune systems are at higher risk for infection, the CDC says.

People who do become infected can experience diarrhea, fever, vomiting, headache or muscle pain. In severe cases, infection can lead to sepsis and even death. About 30 percent of people infected with the bacteria die, according to the CDC.

Cat scratch disease

About 40 percent of cats carry a type of bacteria called Bartonella henselae at some point in their lives, and infection from these bacteria in people causes "cat scratch disease." People can become infected if they are scratched or bitten by a cat, or if a cat licks an open wound on a person. Symptoms of the illness include infection at the wound site, fever, headache, poor appetite, exhaustion and swollen lymph nodes, according to the CDC. In rare cases, the disease may affect the brain, eyes, heart or other organs.

To prevent infection, people should wash cat bites and scratches right away with soap and running water. People with weakened immune systems should avoid adopting cats that are less than 1 year old, because young cats are more likely to carry Bartonella henselae, the CDC says.

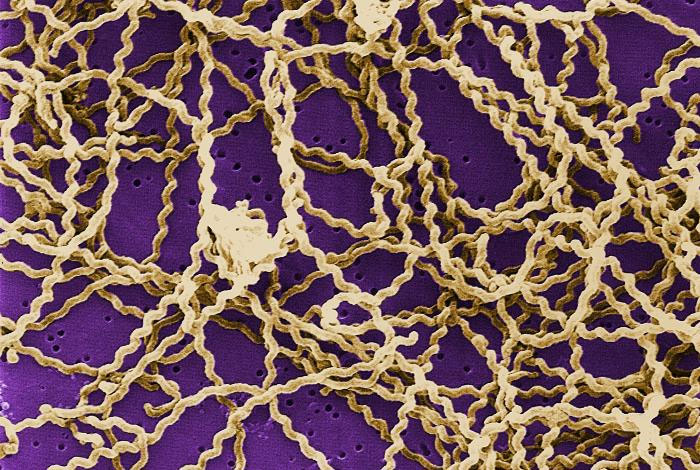

Leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is a disease caused by a spiral-shaped bacterium known as Leptospira, which can infect animals and people. Human cases of leptospirosis are rare in the United States. According to the CDC, only about 100 to 200 leptospirosis cases are reported each year in the United States.

Pets may become infected by drinking contaminated water, or by contact with a wild animal, such as a raccoon or squirrel, that carries Leptospira.

People can become infected with Leptospira if they have contact with the urine of an infected animal, or with an environment that's been contaminated with urine from infected animals, the CDC said. That means that people can get leptospirosis if they have direct or indirect contact with their pet's urine. As a rule, people should always wash their hands after handling their pets or anything that could have their pet's urine on it, the CDC said.

People should also get their pets vaccinated against leptospirosis, although they should be aware that the vaccine is not 100 percent effective at protecting pets against the disease, the CDC said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Flu: Facts about seasonal influenza and bird flu

What is hantavirus? The rare but deadly respiratory illness spread by rodents