Why Other Senses May Be Heightened in Blind People

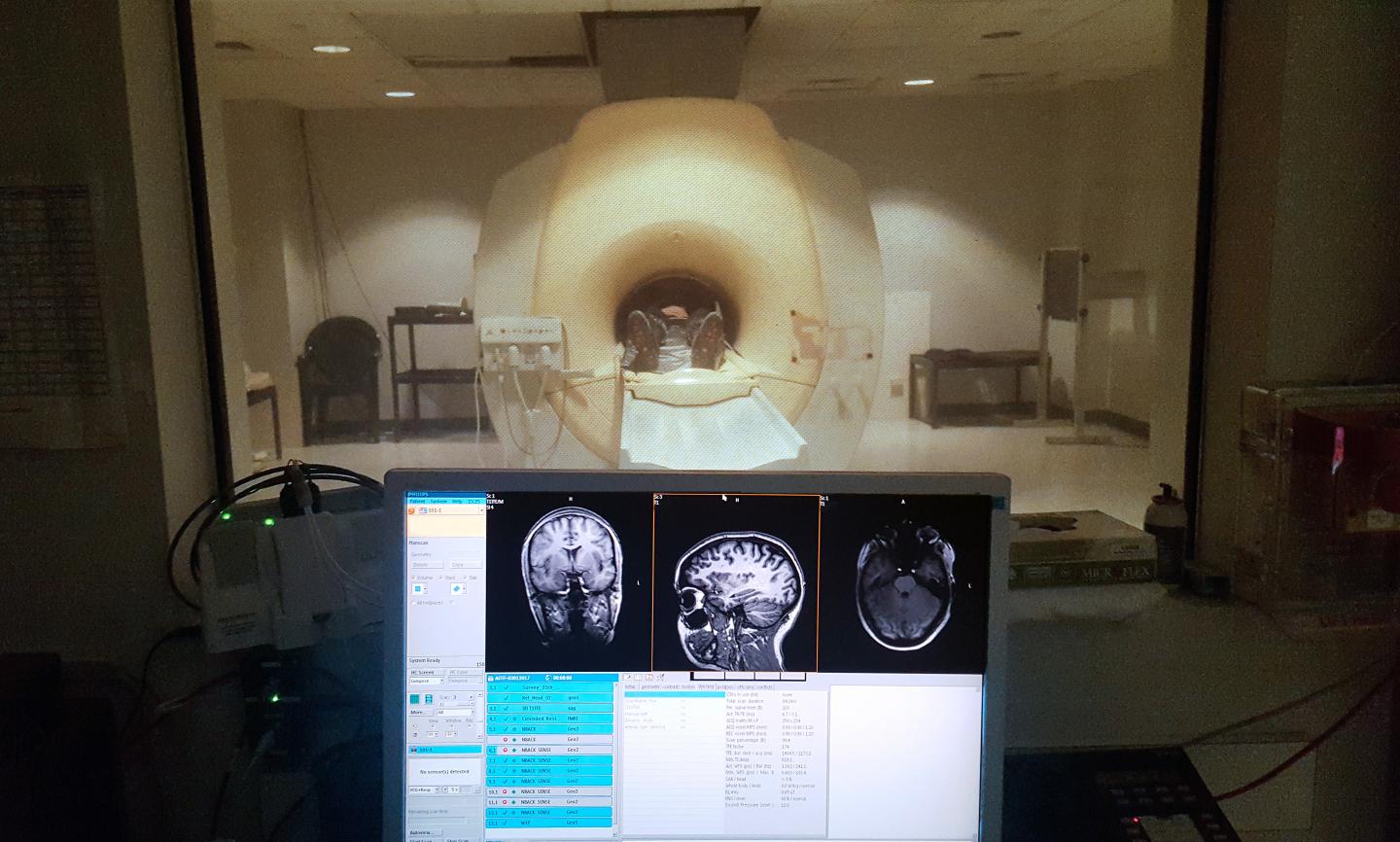

People who are blind really do have enhanced abilities in their other senses, according to a new, small study. The research used detailed brain scans to compare the brains of people who were blind to the brains of people who were not blind.

The study involved people who were either born blind or became blind before age 3. The scans showed that these individuals had heightened senses of hearing, smell and touch compared to the people in the study who were not blind.

In addition, the scans revealed that people who are blind also experienced enhancements in other areas, including in their memory and language abilities, according to the study, published today (March 22) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Such brain changes arise because the brain has a "plastic" quality, meaning that it can make new connections among neurons, the study said. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain]

"Even in the case of being profoundly blind, the brain rewires itself in a manner to use the information at its disposal so that it can interact with the environment in a more effective manner," senior study author Dr. Lotfi Merabet, the director of the Laboratory for Visual Neuroplasticity at Schepens Eye Research Institute of Massachusetts Eye and Ear, said in a statement.

The findings suggest that "there is tremendous potential for the brain to adapt," Merabet said.

In the study, the researchers performed brain scans on 12 people who were blind and 16 people who were not blind. All of the individuals in the study who were blind were "highly independent travelers, employed, college-educated and experienced Braille readers," the researchers noted.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Analyzing the brain scans, the researchers found that there were "extensive morphological, structural and functional" differences in the brains of the people in the study who were blind compared to the brains of the people who were not blind.

"We observed significant changes not only in the occipital cortex (where vision is processed), but also areas implicated in memory, language processing and sensory motor functions," lead study author Corinna Bauer, a scientist at the same institution, said in a statement.

Some of these changes were related to connections in the brain, the scientists found.

For example, the researchers found differences in "white matter connections and functional connections" in the people who were blind compared with those who weren't, Bauer told Live Science. White matter connections are the physical "highways" within the brain through which information flows; functional connections can be thought of as how well brain regions communicate with one another, Bauer said.

The people who were blind had fewer connections between the visual parts of the brain and other areas of the brain," compared with the people who were not blind, Bauer said.

But "there are also areas of the brain, associated with other senses, that are more interconnected," such as areas involved with language and auditory processing, she said. By strengthening the connections among these areas, it appears that brain may be compensating for blindness, she said.

Originally published on Live Science.