The Dinosaur Family Tree Has Been Uprooted

The dinosaur family tree, used by paleontologists and dinosaur buffs for the past 130 years, has just been transformed.

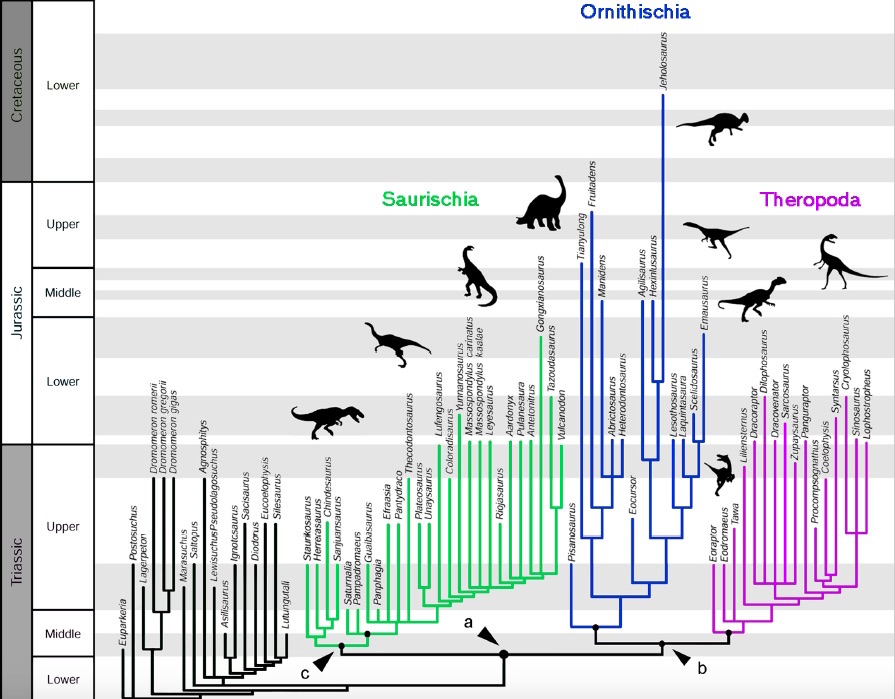

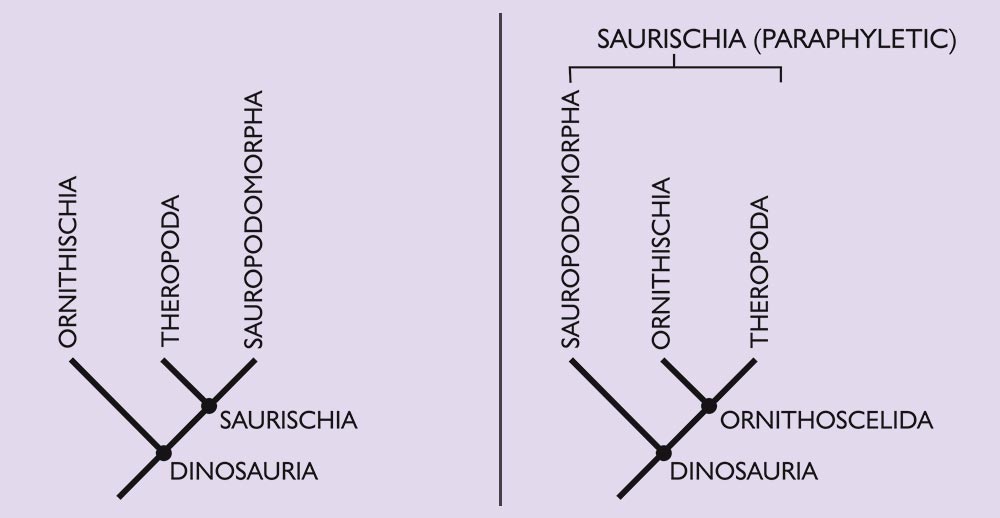

In the old family tree, there are two major groups of dinosaurs: the bird-hipped ornithischian dinosaurs (such as duck-billed dinosaurs and stegosaurs) and the reptile-hipped saurischians, which include the theropods (such as Tyrannosaurus rex) and the sauropods (the long-necked, long-tailed herbivorous giants).

The new study completely reorganizes this setup. According to new analyses, theropods and ornithischians are more closely related than scientists previously thought, and both fit into a previously unknown group called Ornithoscelida, the researchers said. [7 Surprising Dinosaur Facts]

The change may seem small, "as only a few branches are being reshuffled," said Steve Brusatte, a paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland, who was not involved in the study. "But because these are the big branches right near the root of the tree, changing them around is huge. It's saying that much of what we thought about the origins and early history of dinosaurs, going back to the late 1800s, is wrong."

The study also shows that "there is value in going back over old ideas," said study lead researcher Matthew Baron, a doctoral student of paleontology at the University of Cambridge in England. "Just because something has been long believed doesn't mean it's true."

It didn't add up

Baron began the project after noticing that many ornithischians and theropods had similar anatomical features. However, when he read through old studies, he found that countless paleontologists had either overlooked these similarities or dismissed them as being mere coincidences.

But Baron couldn't get these similarities out of his mind. "It just didn't quite add up," he told Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After talking with his adviser, Baron changed his doctoral thesis research to focus on the relationships among early dinosaurs at the base of the family tree. But this was a big undertaking; it required traveling the world to inspect as many early dinosaur specimens as possible, and reading descriptive studies of fossils he couldn't see in person.

"I had one very hectic month in 2015 when I was on four continents in four weeks," Baron said. "I did North America, South America, Africa and parts of Europe."

In all, he and his colleagues looked at 457 anatomical characteristics in each of the 74 species included in the study. Characteristics that were present got a "1" and those that were absent got a "0." If it was hard to tell, the researchers put down a question mark.

"That essentially reduces the skeleton of the species down to a binary code, so each species gets their own bar-code number," Baron said.

The team plugged these bar codes and various evolutionary parameters into a computer program that builds family trees. No matter how many times they changed the parameters and ran the program, they still got one main and "quite shocking" result: a "previously unexpected pairing of theropods and ornithischians," Baron said.

On the other branch, they grouped sauropods with herrerasaurs, early meat-eating dinosaurs that were difficult to classify, though some previously thought they were theropods. This grouping suggests that features shared by the carnivorous herrerasaurs and mostly carnivorous theropods likely evolved independently through convergent evolution, the researchers said.

Feathers and more

The new reorganization may explain why some theropods (the lineage that led to birds) and some ornithischians had feathers. For instance, theropods such as the Cretaceous-age Velociraptor had feathers, but so did Kulindadromeus, an ornithischian dinosaur from the Jurassic period.

The researchers who described Kulindadromeus zabaikalicus in 2014 in the journal Science said they scratched their heads, wondering how a dinosaur that was so far from the lineage leading to birds had feathers, Live Science previously reported.

If the new reorganization is correct, perhaps certain theropods and ornithischian dinosaurs had feathers because their common ancestor did too, the researchers said.

In addition, their models echoed other research suggesting that early dinosaurs were both omnivorous and small, and used their hind legs for walking and two arms for grasping, the researchers said. The analysis also indicates, somewhat unexpectedly, that dinosaurs originated in the Northern Hemisphere, and not in Gondwana, a supercontinent that encompassed Africa, South America, Australia, Antarctica, the Indian subcontinent and the Arabian Peninsula more than 180 million years ago.

The study also bumps back the appearance of the first dinosaurs to 247 million years ago, which is older than the previously accepted date of between 245 million and 240 million years ago, Live Science previously reported.

Revolutionary findings

The new finding about the new Ornithoscelida group is a "bloody big deal," said Thomas Carr, an associate professor of biology at Carthage College in Wisconsin and a vertebrate paleontologist.

"This knocked the wind out me," said Carr, who was not involved in the study. "This is a fundamental shake-up of Dinosauria."

He commended the researchers for doing "their due diligence" in sampling a good number of early dinosaurs and trying different iterations in their family-tree creation. "It looks like the signal is real," he said. However, he noted that other paleontologists will likely reanalyze the new hypothesis in different ways, so it may be years before the world of paleontology fully accepts it.

Retesting is key, Brusatte said. "It's an alluring new study — maybe even a bombshell — but I'm not ready to rewrite the textbooks just yet."

The new study was published online today (March 22) in the journal Nature.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.