Women's Entire Menstrual Cycle Replicated in a Lab

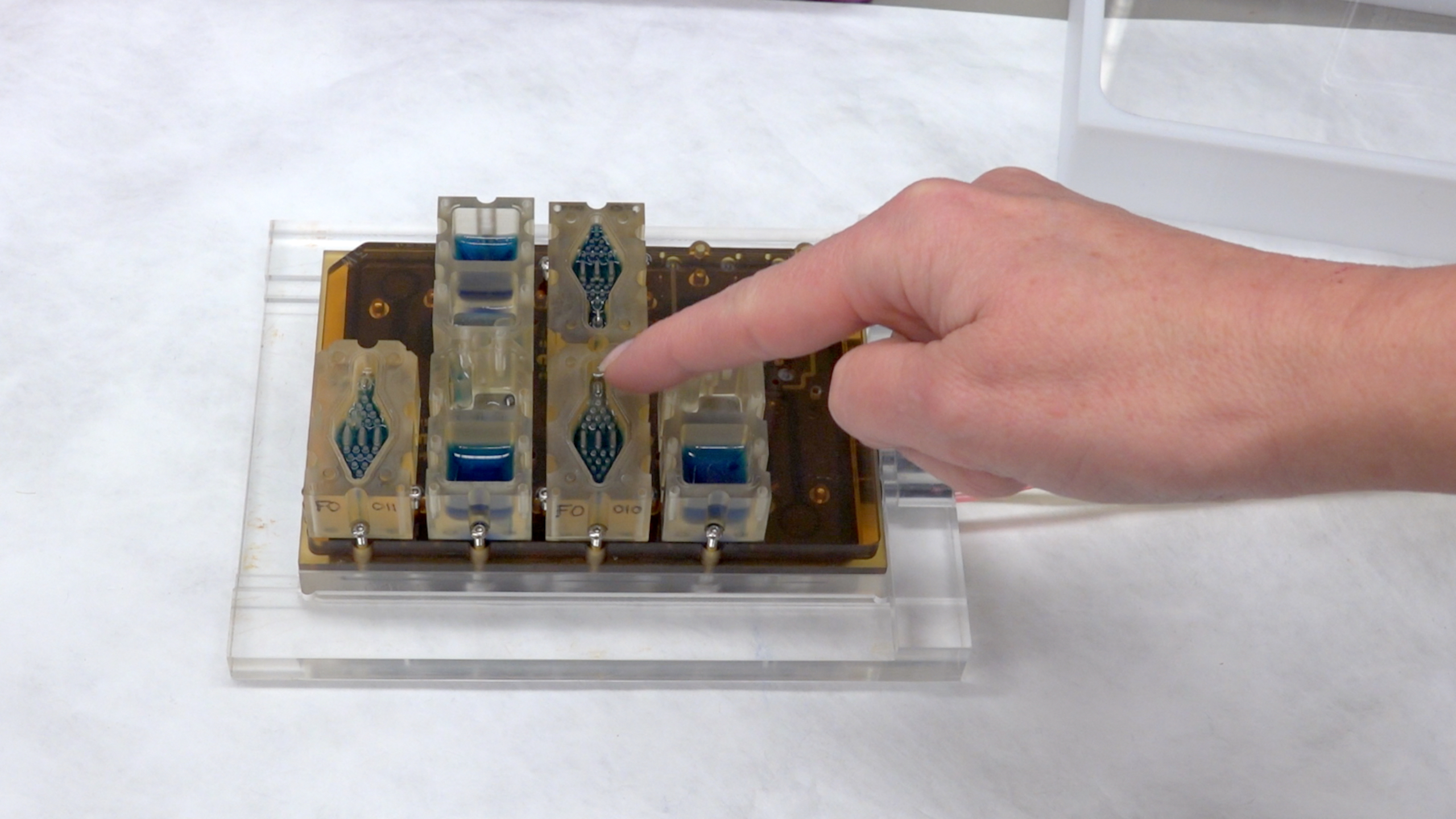

The female reproductive system is such an intricate network of organs and fluctuating hormone levels that it can seem mysterious, even to women. But now, scientists have replicated the entire female menstrual cycle in a bento-box-like device that can fit into the palm of your hand.

The device represents a huge leap beyond the standard plastic petri dish as a medium for studying human biology and developing new disease treatments, the researchers said. It also marks a critical feat in a broader effort to mimic the entire human body in artificial models, they added.

The device includes 3D models of key organs, including the ovaries, fallopian tubes, uterus, liver, cervix and vagina. The tissues for each organ were made from stem cells, and the organs are contained within wells that are interconnected by channels, mimicking the human circulatory system. When the artificial organs secrete substances such as hormones, these substances are carried to the other organs and tissues of the system, triggering various phases of the reproductive cycle. The unit has been shown to operate just as a woman's reproductive tract would over the course of an entire 28-day menstrual cycle. [Video: Lifelike Model of Women's Menstrual Cycle Made in a Lab]

"We think we can go longer, but what we're reporting is 28 days," said lead researcher Teresa Woodruff,director of the Women's Health Research Institute at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, in Chicago."What we're mimicking here is the menstrual cycle itself."

Woodruff and her team named the device EVATAR —like "avatar," but female.

"Avatars are representations of actual people," Woodruff told Live Science. "Eve is kind of the mother of all humans; EVATAR is kind of the mother of all microhumans."

EVATAR is the culmination of five years of work by separate teams that were each assigned an organ to create "in a cube."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Scientists at Woodruff's lab, along with researchers at MIT, developed the ovaries. Julie Kim, an associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern, created the uterus. Spiro Getsios, an assistant professor in dermatology and cell and molecular biology at Northwestern, developed the cervix and vagina; and Joanna Burdette, of the University of Illinois at Chicago, developed the fallopian tubes. EVATAR also includes an artificial liver, because that organ metabolizes many drugs that people might take.

Most of the organs in the unit were developed using induced pluripotent stem cells, which are stem cells that are made from adult skin or blood cells that have been triggered to develop into tissue for a specific organ. [The 7 Biggest Mysteries of the Human Body]

The key advance of EVATAR is that each organ in the unit is connected by an artificial circulatory system.

"This mimics what actually happens in the body," Woodruff said in a statement from Northwestern University.

Potential applications

Woodruff said that EVATAR could improve researchers' understanding of the female body and help to guide the development of much-needed drugs to treat conditions such as fibroids, endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and many cancers. [5 Things Women Should Know About Ovarian Cancer]

Endometriosisaffects an estimated 10 percent women during their reproductive years, according to the National Institutes of Health. PCOS affects between 5 and 10 percent of women, according to the NIH. Currently, there are very few treatments, other than surgery, for women with these conditions.

Hormones play a key role in these conditions, as well as in many cancers. EVATAR will help researchers to factor in the role of hormones when they study reproductive diseases, according to the researchers' paper, published today(March 28) in the journal Nature Communications.

"The systems are tremendous for the study of cancer, which often is studied as isolated cells rather than system-wide cells," Burdette said in the statement. "This is going to change the way we study cancer."

Another area of research that EVATAR could boost is fertility treatment, particularly for women who have had cancer and have undergone radiation and chemotherapy, which can damage a woman's ability to produce viable eggs, Woodruff said. By mimicking the body's ability to produce eggs, the devices could offer new insight into better ways to grow eggs outside the body.

The devices could also prove useful in finding new birth control drugs that could be taken less frequently than the standard daily pill, said Woodruff, who has a grant from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to develop new contraceptive options for women.

EVATAR is part of a broader NIH project that aims to improve the success rate of new drugs. Currently, drugs are tested in labs and in animal models, said Danilo Tagle, an associate director of the NIH project. But 90 percent of the drugs tested this way fail to work in people, he said.

"That's a lot of wasted expense," Tagle said.

So far, the group has overseen the creation of models of a liver on a chip, a heart on a chip, the human brain on a chip and, most recently, the creation of an artificial human gut that tests how certain drugs are processed by the digestive system. [7 Facts Women (And Men) Should Know About the Vagina]

Of the NIH-funded projects to create artificial organs and systems, EVATAR is among the most complex so far, because it incorporates the hormonal changes of a complete 28-day menstrual cycle, Tagle said. Woodruff and others imagine a time when models such as EVATAR will be scaled up to include the entire human body.

"In the long run, we can create an entire personalized system for individuals where artificial organs are derived from a person's own tissue," she said. "In this way, we could provide a personalized source of testing drug toxicity and drug efficacy that we just don't have at this point."

Woodruff's team is now working on a male version of EVATAR, currently dubbed ADATAR, that mimics the male reproductive system.

In medical research, it has been unusual for studies to focus first (if at all) on female models, often due to sexism. But in this case, starting with the female reproductive tract was useful because there are clear markers (such as ovulation and the shedding of the uterine lining) that their team could look for to make sure their unit was functioning, Woodruff explained.

"When you're building a brand-new, engineered system like this, it's critical to have these predicted outcomes as positive controls," she said. In other words, the team could see that organs in the artificial unit were functioning and interacting as the unit displayed the various phases of the menstrual cycle.

Plus, she added, it's about time a female biological model came first.

Original article on Live Science.