Plant Photos: Amazing Botanical Shots by Karl Blossfeldt

Plant Portraits

Karl Blossfeldt (June 13, 1865 – December 9, 1932), a German photographer, sculptor and teacher, is best known for his extreme close-ups of plants, which he used mainly as visual teaching aids. Blossfeldt's teacher at the Royal Museum of Arts and Crafts in Berlin, Moritz Meurer assembled bronze sculptures based on botanical forms. According to the foreword of a new collection of Blossfeldt's works, called "Karl Blossfeldt: Masterworks" (D.A.P., 2017), the artist became both sculptor and photographer for the casts. "Producing these photographs required a great deal of talent," the foreword reads. "The first task was to capture the essence of the plant, but at what moment, and in what state, should it be captured? What idea was most associated with its image? How should buds and fruits be arranged, in order to highlight their most striking features?

The results were "strikingly austere yet poetic," according to the book's publisher.

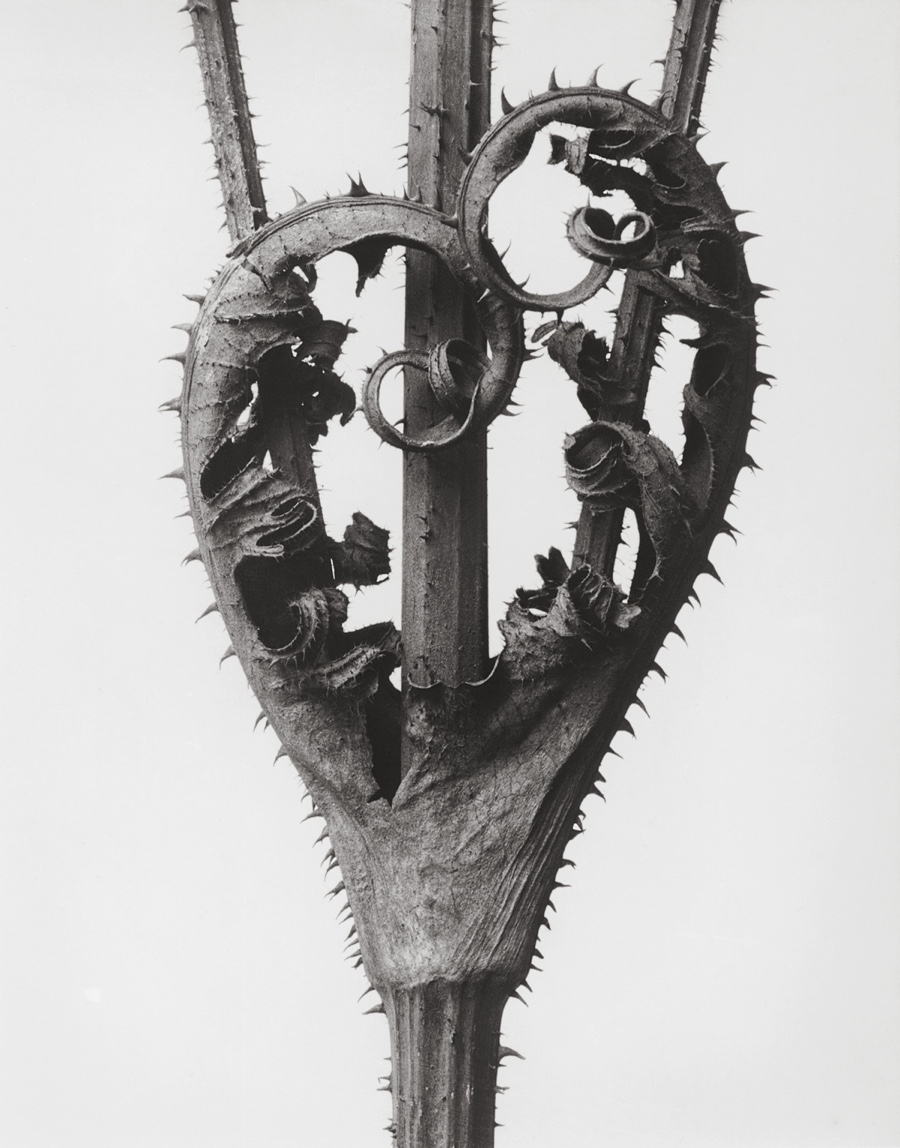

Bear's breeches

In addition to the artistic side of Blossfeldt's portraits, there were also many technical aspects involved. For instance, he wanted only the plant to be visible in the photo, no background. "The image also had to feature all the details required for the sculpting that was to follow," according to the book's foreword. Shown here, bear's breeches (Acanthus mollis, revealing its flowering stem with bracts after the flowers had been removed.

Oriental poppy

The flower bud of the oriental poppy, Papaver orientale. "The oriental poppy is the largest member of the poppy family, and can reach more than 1 meter (3.25 ft) in height, with leaves in the form of a rosette and sturdy stems with bristles," according to the book.

Sea holly

In order to illuminate the plants from various and ensure they didn't cast any shadows, Blossfeldt would arrange his subjects on a sheet of glass placed well above the floor or other surface. However, when the plant's parts (fruits, seeds and flowers) were lit equally from all angles, their "curved forms are distorted," making it critical that Blossfeldt illuminated one side more than the others, according to the book.

Shown here, the leaf of the Mediterranean sea holly, ryngium bourgatii.

Furled frond

A young, furled frond of the Western swordfern, Polystichum munitum. The dark-green fronds of this fern grow from an underground rhizome and can reach heights of 6.5 feet (2 meters).

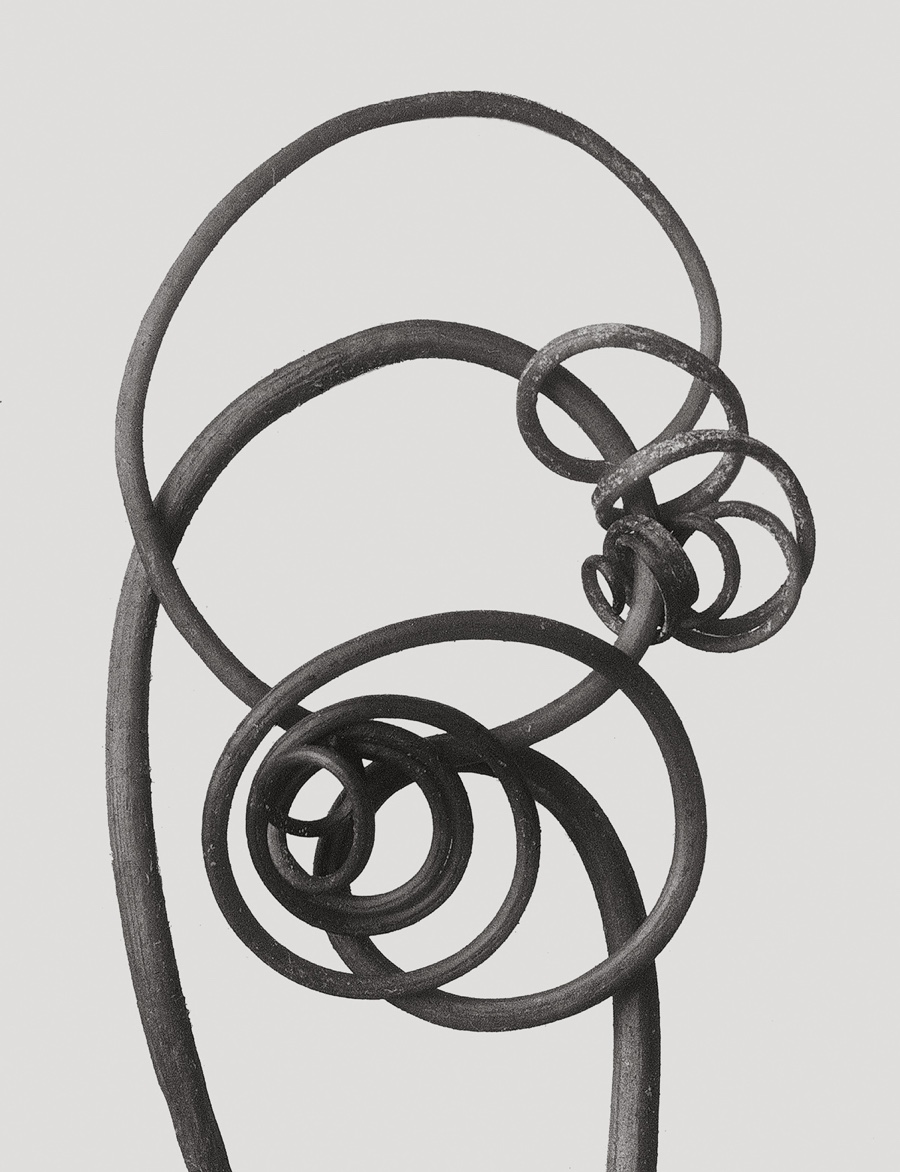

Pumpkin tendrils

The tendrils of a pumpkin plant, a species in the Cucurbita genus.

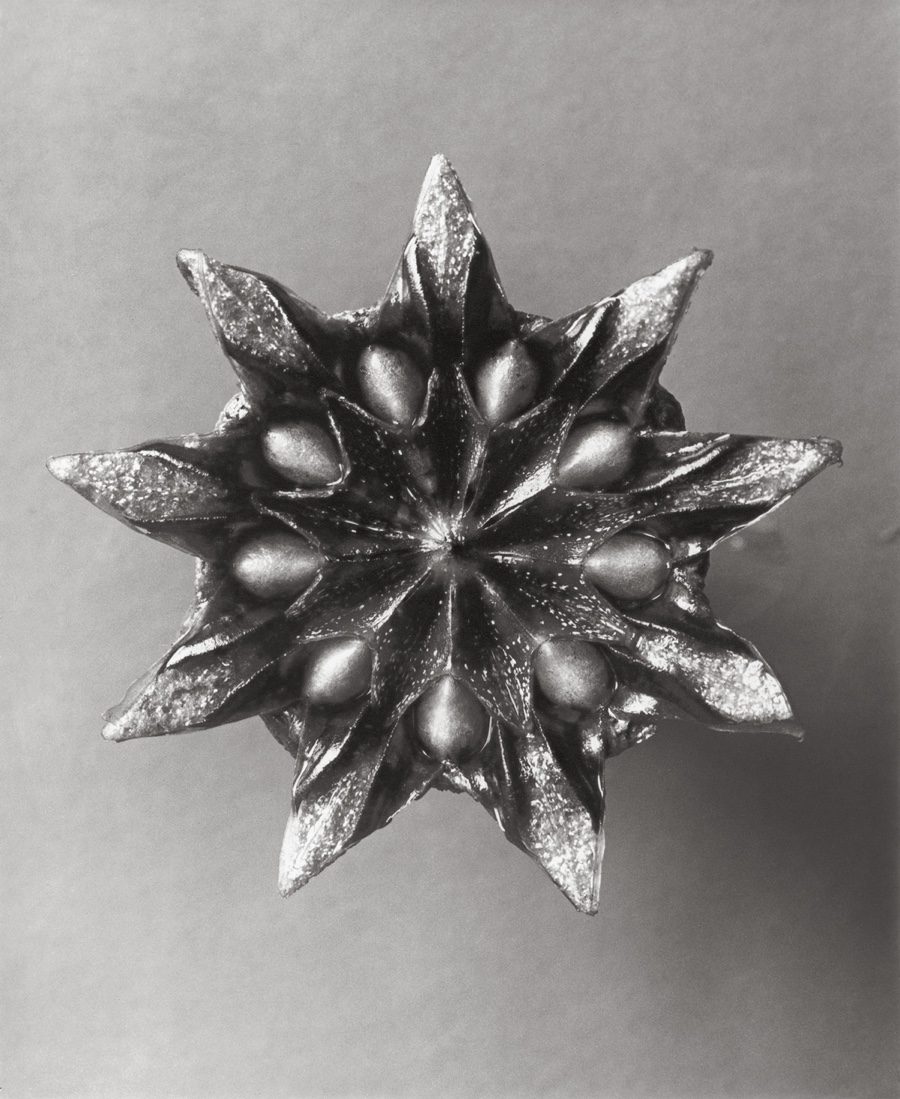

Seed heads

Seed heads of a saw-wort, Serratula nudicaulis.

Pink lily

The flower head, or umbel, of the pink lily leek, Allium oreophilum. The flowers of this lily have six petals that are arranged in two whorls (three petals each). Before the lily flowers, its buds are enclosed in thin bracts. Blossfeldt's photograph shows the moment when the petals have just emerged from the bracts," according to the book.

Fig marigold

The seed head of the tongue-leaved fig marigold, Mesembryanthemum linguiforme. The book notes that in 1977, a German scientist named Karl Gottfried Hagen, wrote about "a mysterious plant that has neither anthers nor stigmas, which grows underground like a truffle in the Cape, South Africa, and only sometimes emerges after a spell of warm rain." The next year, Abraham Abendroth said that mysterious plant was in fact the seed head of Mesembryanthemum linguiforme, which can grow when it is wetted.

Cutleaf teasel

The stem and leaves of the cutleaf teasel, Dipsacus laciniatus. Its prickly flower heads may have once been used as combs to raise the nap of textiles like wool.

Maidenhair fern

A young, unfurling frond of the maidenhair fern, Adiantum pedatum. The frond can grow up to 20 inches (50 cm (20 centimeters) tall. Rather than growing individually like other ferns, this one grows in a branching arrangement that "resembles a fan or a peacock's tail," according to the book.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.