Volcanic Activity on Ancient Mars May Have Produced Organic Life

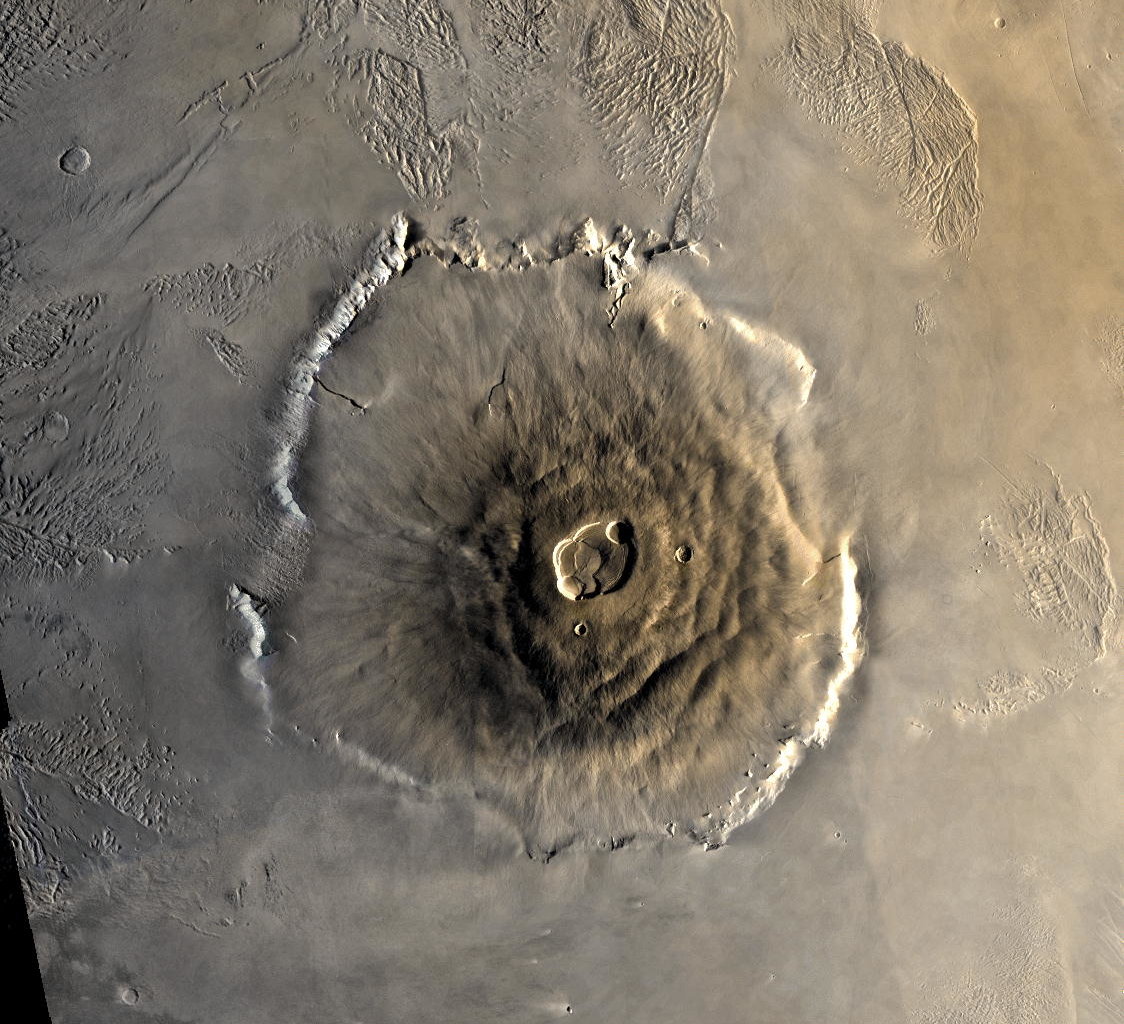

Even a cursory look at a global map of Mars reveals how huge its volcanoes are. The famous Olympus Mons rises three times higher than Mt. Everest, and is just one of several volcanoes that adorn the Red Planet's famous Tharsis ridge. Presumably, when these volcanoes were more actively spewing gases such as carbon monoxide and sulfur, they must have had a determining influence on the Martian atmosphere.

A new paper in the journal Icarus suggests that these volcanoes may in fact have created an environment habitable to ancient microbes. Specifically, a new model showing a range of volcanic eruptions shows that Mars' atmosphere could have been made anoxic, with depleted levels of oxygen and limited oxygen-based reactions.

"These results imply that ancient Mars should have experienced periods with anoxic and reducing atmospheres even through the mid-Amazonian whenever volcanic outgassing was sustained at sufficient levels," the researchers wrote. "Reducing anoxic conditions are potentially conducive to the synthesis of prebiotic organic compounds, such as amino acids, and are therefore relevant to the possibility of life on Mars."

"This is important from an astrobiology standpoint because these reducing anoxic conditions have been hypothesized as being important to the origin of life on the early Earth," said lead author Stephen Sholes, a Ph.D. candidate in earth and space sciences and astrobiology at the University of Washington, said in an e-mail to Seeker.

RELATED: How Mars Went From Warm and Wet to Cold and Dry

He pointed out that the famous Urey-Miller experiments of the 1950s showed that electrical pulses, in an environment with a reducing atmosphere and liquid water, produced complex organic molecules. By contrast, an oxidizing atmosphere would also oxidize these molecules, making them less useful in supporting the formation of life.

While volcanism on the Red Planet has been discussed for decades, Sholes said his research is different because it is quantifying how much volcanism is required to create reducing atmospheres on Mars. Specifically, his work delves into what it would take to do so, whether it is feasible, and how it could be detected.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Another difference is the approach itself. Other models that discuss volcano-atmosphere reactions on Mars focus on how the planet could be warmed, Sholes said, using outgassed volcanic gasses.

"Yes, you need liquid water, but you also need appropriate conditions for life, and here we are finding that the volcanoes should have changed the atmosphere enough to be more conducive to forming complex bio-important molecules," he said.

If the atmosphere was anoxic, scientists may be able to see the evidence on the ground, even billions of years later. That's because anoxic conditions should alter the types of minerals and rocks that form, allowing for testable predictions for future Mars missions. Examples include minerals made of ferrous iron — such as siderite, or iron carbonate — as well as elemental sulfur.

"Our results show that, given models for volcanic activity, during periods of sustained volcanism, Mars’ atmosphere could easily shift towards reducing and anoxic conditions, thus producing measurable amounts of elemental sulfur deposits," Sholes said.

RELATED: Colonizing Mars Might Require Humans to Radically Alter Their Bodies and Minds

He added that elemental sulfur has not been found yet on Mars, but it is a difficult mineral to study.

"The measurement techniques used could actually cause it to breakdown into smaller molecules that could be misidentified," he said.

Two missions are specifically investigating the Martian atmosphere right now. NASA's MAVEN (Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution), which primarily examines atmospheric loss, and the European Space Agency's TGO (Trace Gas Orbiter), which looks at minority molecules in the Martian atmosphere.

Sholes said the atmosphere does not preserve tracers of past reducing conditions, so the current missions would not help us learn directly about past volcanic activity. Their measurements will help refine the atmospheric models used, however.

"Eventually we would like to update the model to test how single eruption events would change the atmosphere and the timescales involved," he added. "Our current model assumes constant volcanic eruptions, which wouldn’t necessarily be the case. If we could test individual eruptions, we could learn how big of an eruption would be required to switch the atmosphere anoxic, and how long that atmosphere would last before it would switch back."

Originally published on Seeker.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.