First Animal? Jellyfish May Take the Prize

If scientists were to draw an enormous family tree for all of Earth's animals, the oldest branch would belong to the jellyfish, a new study finds.

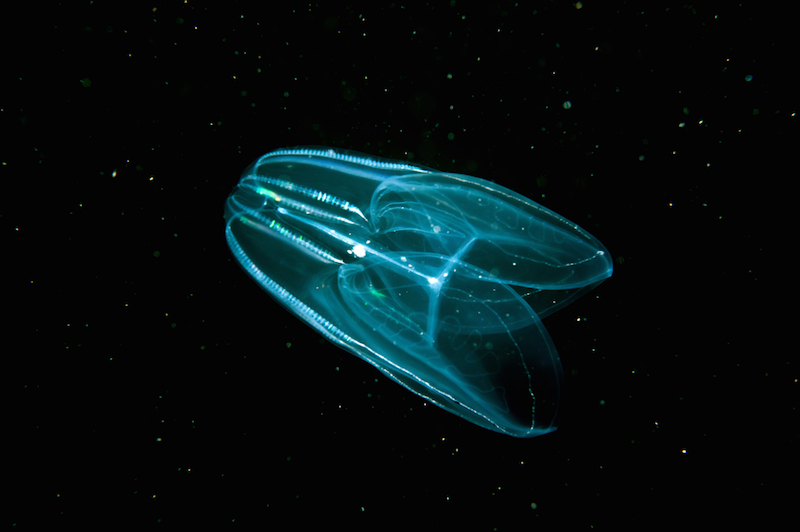

The result is the latest in a decade-long debate over which came first: the jellyfish or the sponge. The sponge has long been a crowd favorite because its body is extremely simple when compared with other animals. But a new, detailed genetic analysis revealed that the delicate predator the comb jelly (a ctenophore) evolved first, the researchers in the new study said.

The results will help scientists determine how the nervous system, digestive tract and other basic organs evolved in animals, the researchers said. [7 Theories on the Origin of Life]

The debate began in 2008, when a family-tree study pointed not to sponges — long identified as the "earliest animal" — but to comb jellies as the earliest members of the animal kingdom. In the following years, scientists published papers with conflicting results. The latest study, which came out online in March in the journal Current Biology, showed an impressive genetic dataset supporting the sponges' position at the base of the family tree, the researchers said.

But while these "big data" approaches work in 95 percent of all family-tree cases, "it has led to apparently irreconcilable differences in the remaining 5 percent," study senior researcher Antonis Rokas, a professor of biological sciences at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee, said in a statement.

To investigate, Rokas and his colleagues looked at 18 controversial relationships — seven from animals, five from plants and six from fungi — to learn why these parts of the family tree provoked so many conflicting results. The researchers did this via a lengthy comparison of individual genes from each contender (such as the jellies and sponges) to many of the contenders' relatives on the family tree, the scientists said.

"In these analyses, we only use genes that are shared across all organisms," Rokas said. "The trick is to examine the gene sequences from different organisms to figure out who they [the sequences] identify as their closest relatives. When you look at a particular gene in an organism — let's call it A — we ask if it is most closely related to its counterpart in organism B, or to its counterpart in organism C, and by how much."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers studied thousands of genes to find how many genes from each animal — in this case, the sponge and the comb jelly — had the most support for being the first animal in the family tree. The one with more genes in common with its close relatives had higher phylogenetic signals. (Phylogeny is the scientific term for family tree.)

The earlier an animal emerged on Earth, the earlier it likely diverged into new species, the researchers said. As such, that organism would have more related species and so a higher phylogenetic signal. The new study's results revealed that the comb jelly had more genes that support the "first-to-diverge" status than the sponges did.

The team also examined whether crocodiles were more closely related to birds or turtles. Among these animals, 74 percent of the shared genes favored the idea that crocodiles and turtles were sister lineages, while birds were close cousins. [Dangers in the Deep: 10 Scariest Sea Creatures]

The holdup

Just one or two "strongly opinionated genes," or those that have strong phylogenetic signal for one of the specific hypotheses tested over the other (for instance, such a gene might strongly favor "sponges-first" over "jellies-first"), likely led to the contentious results in other studies, the researchers in the new study said. Statistical methods used in earlier studies were highly susceptible to the influence of these genes, the researchers said.

The removal of even one opinionated gene can flip the results' conclusion about which candidate appeared first, the researchers said. They found that when this happens, the mystery may never be solved, either because the data are inadequate or because the diversification happened too fast for researchers to determine which candidate arose first.

Even so, the new analysis does solve some of the less contentious issues, the researchers said.

"We believe that our approach can help resolve many of these long-standing controversies and raise the game of phylogenetic reconstruction to a new level," Rokas said.

The study was published online today (April 10) in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.