The science behind the 10 plagues of Egypt

Some of the diseases and natural disasters chronicled in the Book of Exodus can be explained by scientific theories.

Every year in March or April, Jewish people around the world celebrate Passover — a holiday that marks the Exodus, when the Jews escaped slavery in Egypt and moved to Israel, as recounted in the Torah (the Hebrew Bible, which collects the first five books of the Christian Old Testament).

Before Moses could lead the 40-year journey through the desert, he needed the pharaoh's permission to free the Jews from enslavement, according to the Torah. Egypt’s ruler had a hard heart, however, prompting the Lord to send down 10 plagues until the pharaoh changed his mind.

Could any of Egypt’s plagues have occurred through natural phenomena, rather than an actual act of God? Live Science looks at possible scientific explanations behind each of the 10 plagues.

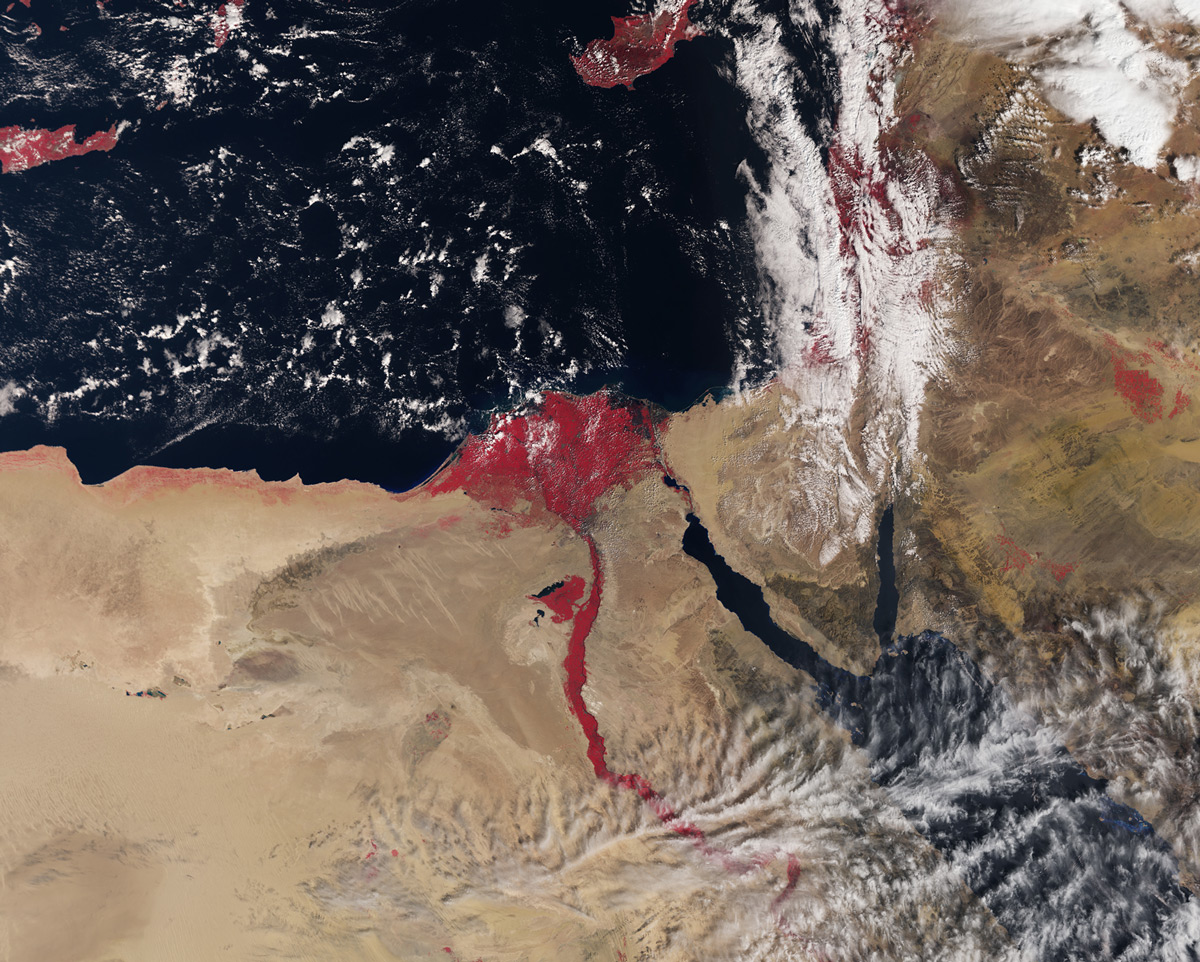

Blood

To unleash the first plague upon the Egyptians, Moses struck the river Nile with his staff, turning its waters to blood. At the same time, his brother Aaron similarly transformed canals, tributaries, ponds and pools throughout Egypt.

After the water turned to blood, "the fish in the Nile died, and the Nile stank, so that the Egyptians could not drink water," according to the Hebrew Bible (Exodus, chapter 7, verse 21).

How can science explain this transformation? The sudden appearance of red-hued waters in the Nile could have been caused by a rapid bloom of red algae. This occurs when certain conditions — such as more light or nutrients — enable microscopic algae to reproduce to such an extent that the waters they live in appear to be stained a bloody red.

This phenomenon is known as a "red tide" when it happens in oceans, however red algae are also commonly found in freshwater ecosystems. These so-called algal blooms can be harmful to wildlife as the algae produce toxins that can kill fish and make shellfish dangerous to eat. Fumes from densely-concentrated algal blooms can also disperse toxins in the air, causing breathing problems in exposed individuals.

Frogs

For the second plague, Moses conjured vast quantities of frogs that swarmed into people's homes — some even found their way into the Egyptians' beds, ovens and cookware.

As it happens, the phenomenon of "raining frogs" has been reported multiple times around the world throughout history. For instance, an 1873 report in the magazine Scientific American described a "shower of frogs" caused by a rainstorm in Kansas City, Missouri. These kinds of events may have been the result of strong winds carrying frogs from one place to the next.

More recently, in May 2010, thousands of frogs emerged from a lake in northern Greece likely in search of food — which disrupted traffic for days, CBS News reported.

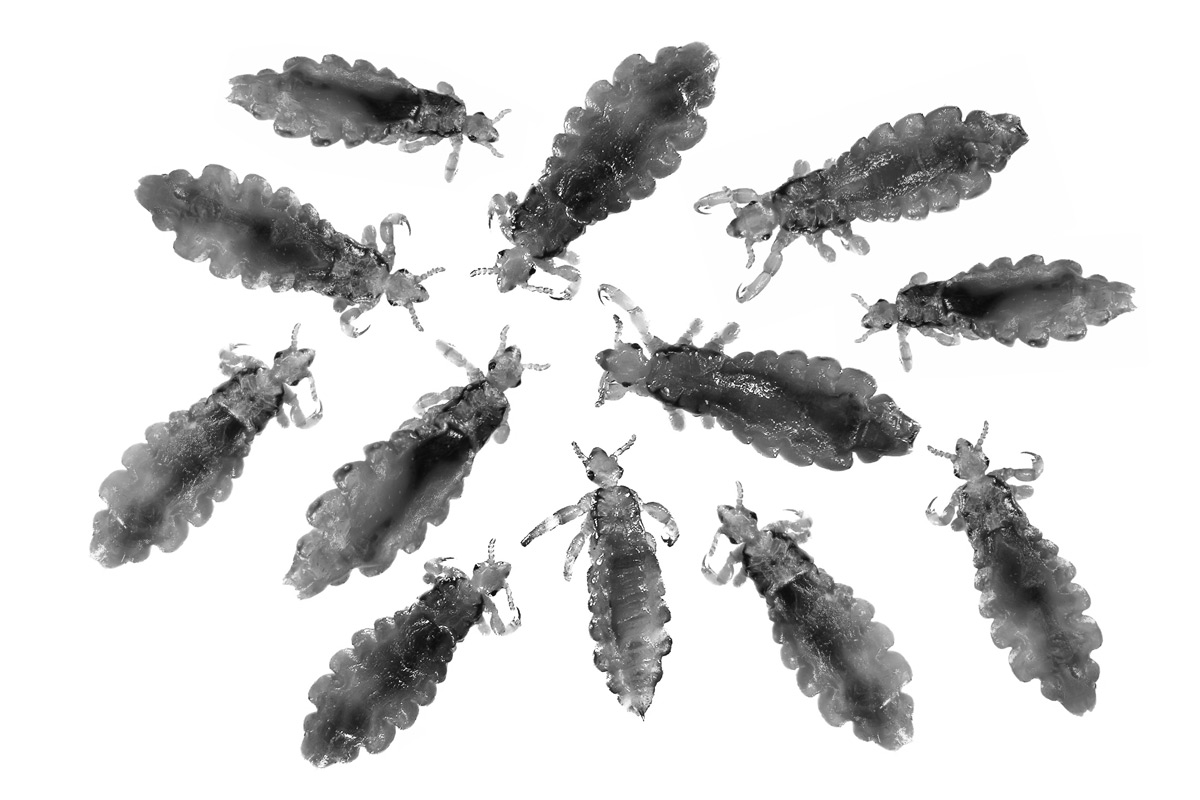

Lice

The third plague, lice, could mean either lice, fleas or gnats based on the Hebrew word, "Keenim."

If a toxic algal bloom caused the first plague and a pile of dead frogs followed, it's not surprising that a swarm of insects of some sort came after. That's because frogs typically eat insects so without them, the fly population could have exploded, said Stephan Pflugmacher, during a National Geographic television special about the plagues in 2010. At the time, Plufmacher was a climatologist at the Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries in Berlin.

What makes this particular event worse is that both body lice and fleas can theoretically transmit the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which causes bubonic plague. A louse infestation could have set the stage for the later plagues, such as boils.

Scientists have also argued that the sickness that later killed livestock may have been the viral infectious diseases Bluetongue or African horse sickness — both of which can be spread by these plague insects.

Related: Ancient Judeans ate non-kosher fish, archaeologists find

Wild beasts

The Hebrew word for the fourth plague, "arov," is ambiguous. The word roughly translates to "a mixture" in English and, over the years, rabbis have interpreted this to mean wild animals, hornets or mosquitoes, or even a wolf-like beast that attacks at night.

The plague of wild beasts may also have been referring to an array of different types of animals, including snakes, scorpions, and even lions and bears.

Conversely, in a 1996 paper that tried to provide epidemiological explanations for the plagues, scientists John Marr and Curtis Malloy argued that the beasts in the fourth plague were most likely stable flies (Stomoxys calcitrans).

Bites from these flies may have led to the boils that occurred later on in the story, Marr and Malloy suggested.

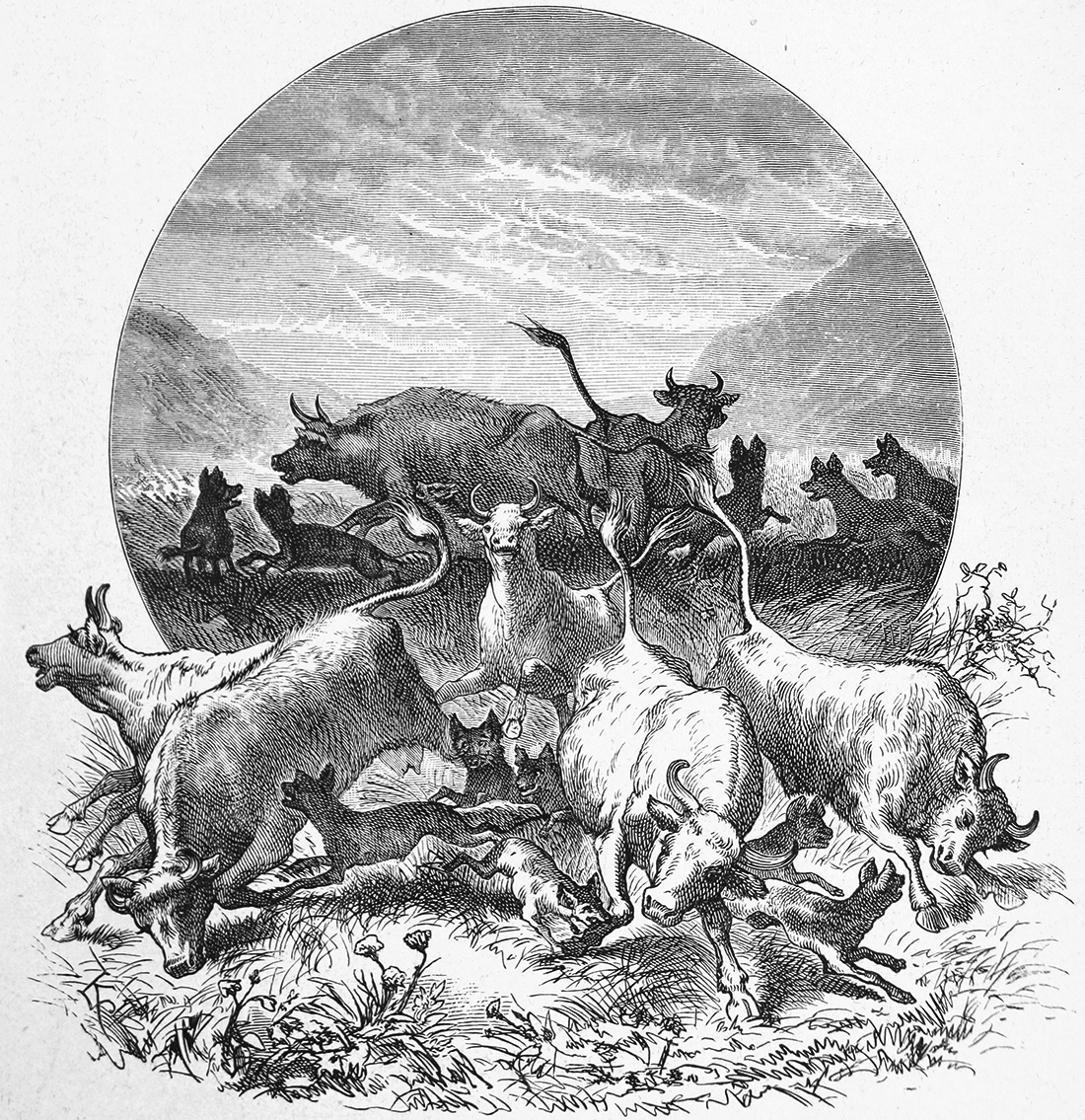

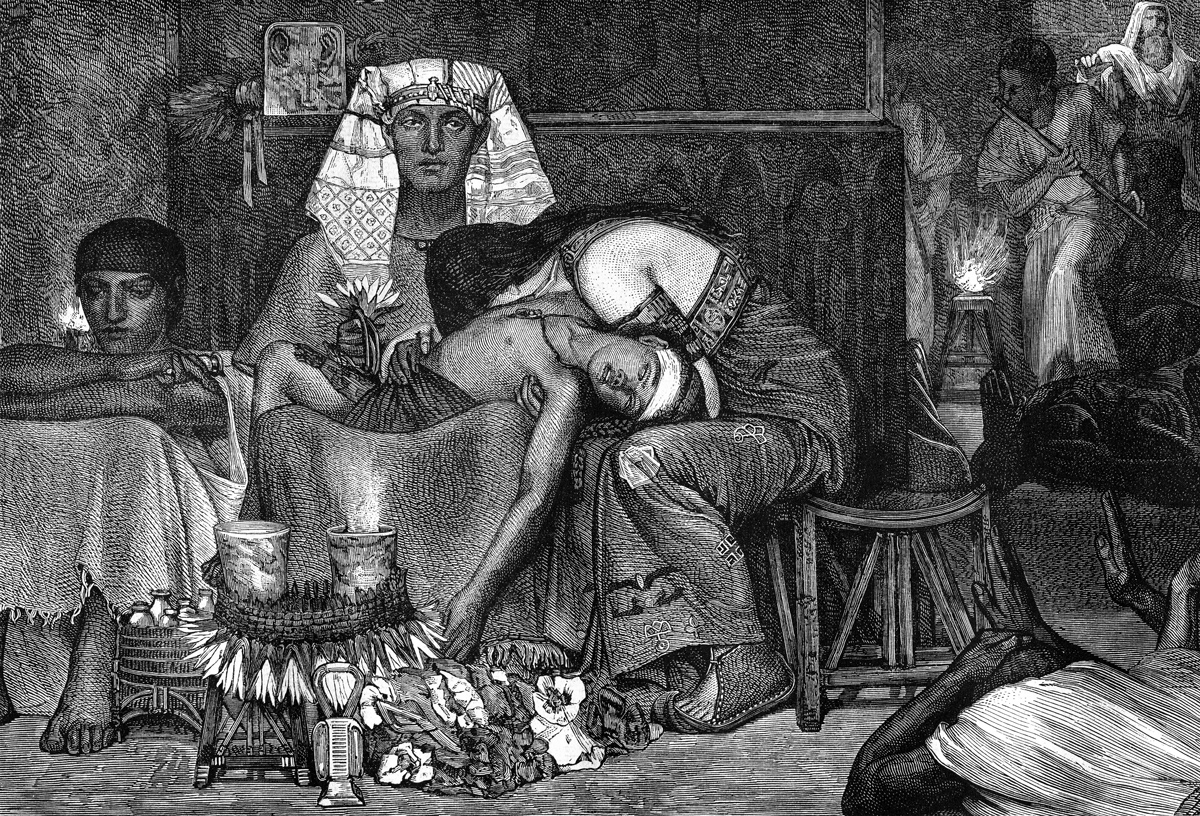

Diseased livestock

The fifth plague called down on Egypt was a mysterious and highly contagious disease that swiftly killed off the local livestock. This biblical scourge is reminiscent of a real plague known as rinderpest — a now-eradicated, infectious and deadly viral disease that decimated populations of cattle and other ruminants across Europe and Africa during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Rinderpest was caused by a virus in the same family as the canine distemper virus and the human measles virus. The disease caused a range of symptoms in infected animals, such as a high fever, diarrhea, dehydration and mouth ulcers.

The disease is thought to have originated in Asia approximately 10,000 years ago, when the extinct ancestors of modern cattle were first domesticated. It is believed to have reached Egypt along prehistoric trading routes around 5,000 years ago.

The fatality rate of rinderpest was exceptionally high — sometimes reaching 100% — and resulted in the deaths of millions of cattle globally before it was eradicated in 2010.

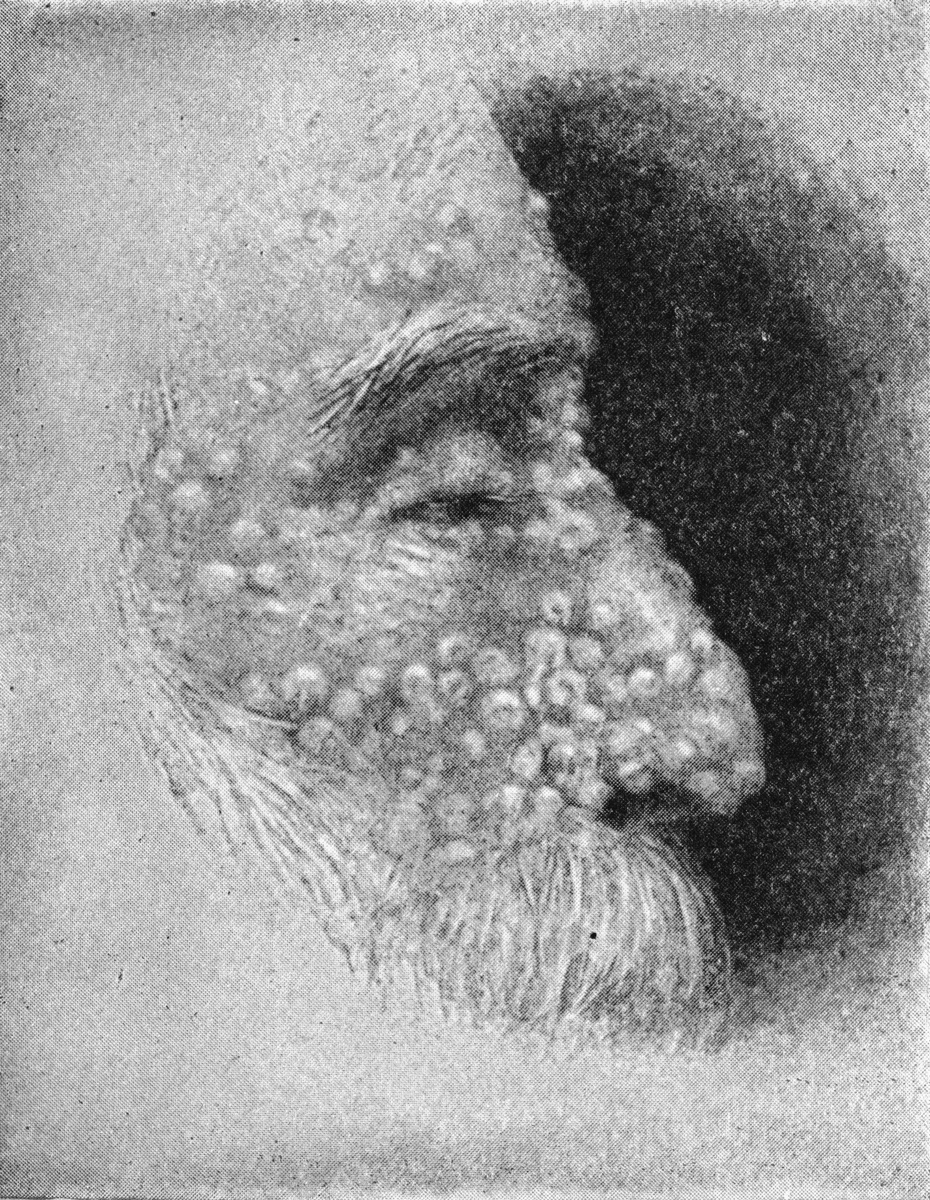

Boils

Shortly after the Egyptians' livestock died off, they were distracted by the sixth plague — an extremely uncomfortable plague of boils that covered their bodies. Boils are painful, pus-filled bumps that form under the skin. They are typically caused by a species of bacteria known as Staphylococcus aureus that is commonly found on skin and inside the nose.

An outbreak of the highly infectious and now eradicated disease smallpox —which caused distinctive raised blisters — could result in masses of people simultaneously coming down with rashes and welts. Smallpox is thought to have affected communities in Egypt at least 3,000 years ago, based on evidence of scars found on mummies dating back to that period.

Related: Trove of Jewish artifacts discovered beneath a synagogue destroyed by Nazis during WWII

Fiery hail

The seventh plague brought a heavy hail accompanied by thunder and streaming fire. This chaotic weather struck down people, livestock and trees, although the area of Goshen — where the Israelites lived — was spared, according to the Torah (Exodus, 9:27).

A nearby volcanic eruption around 3,500 years ago on the Greek island of Santorini may explain this plague, as well as others. It's possible that the volcanic ash mixed with thunderstorms above Egypt, leading to dramatic hailstorms, an astrophysicist told the Telegraph.

Locusts

When the pharaoh once more refused to let the Jewish people go, hungry locusts descend as the eighth plague. As Moses warned the pharaoh: "They shall cover the face of the land, so that no one can see the land" (Exodus 10:5). Such a pestilence would devour all the remaining plants that the hail did not destroy, Moses also said.

The volcanic eruption on Santorini may have created favorable conditions for the locusts, Siro Trevisanato, a Canadian molecular biologist and author of "The Plagues of Egypt: Archaeology, History and Science Look at the Bible" (Gorgias Press, 2005), told The Telegraph.

"The ash fallout caused weather anomalies, which translates into higher precipitations, higher humidity," Trevisanato said. "And that's exactly what fosters the presence of the locusts."

Darkness

The darkness that descended on Egypt for three days as the ninth plague may have been a solar eclipse or a cloud of volcanic ash, scholars suggest.

For instance, one theory is that the darkness may have coincided with an eclipse on March 5, 1223 B.C. However, the fact that the Israelites still had light in their homes during the plague of darkness weakens this hypothesis.

An alternative theory is that the volcanic eruption on Santorini approximately 3,500 years ago spewed ash that caused the darkness, reported The Telegraph. Indeed, scientists have discovered bits of glass from the volcano in the sole of the Nile delta, according to The New York Times. However, the eruption happened about 500 miles (800 kilometers) from Egypt and before the Exodus event took place, reducing the validity of this theory, argued The Christian Courier.

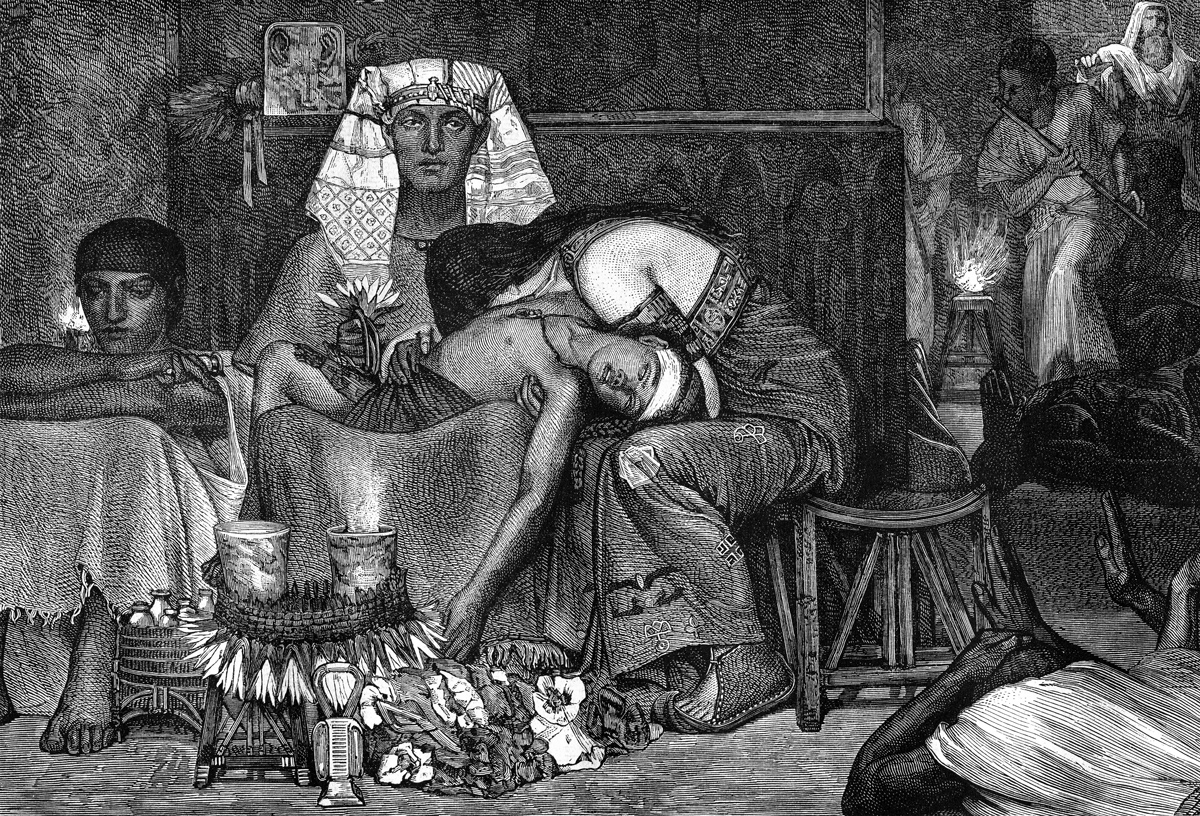

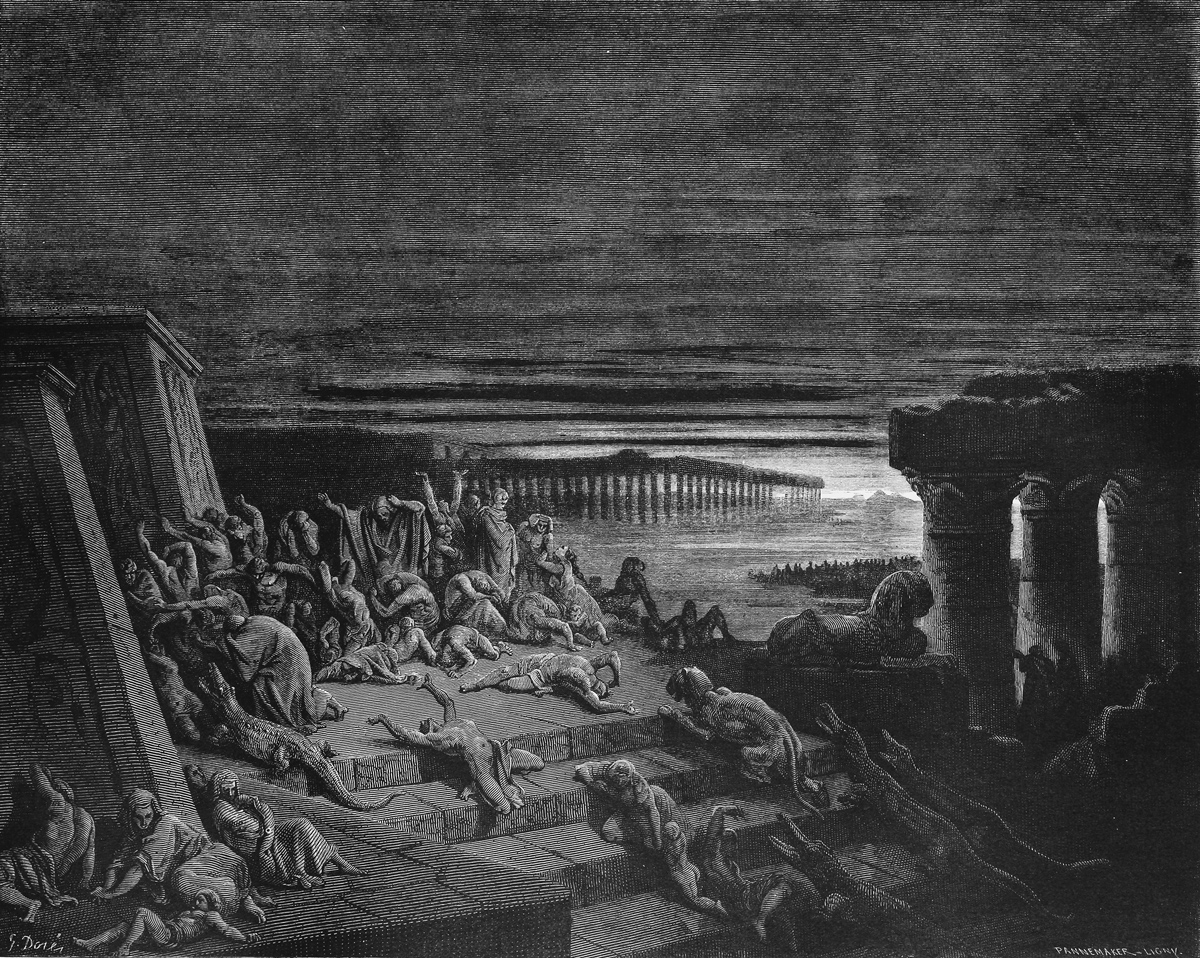

Killing of the firstborn

In the 10th and final plague, Moses tells the pharaoh that all firstborns in the land of Egypt would die.

Some scholars argue that a possible explanation for this plague is that firstborns died after eating grain that was contaminated with mycotoxins in moldy granaries. Mycotoxins are poisonous substances that can cause illness and death in humans and other animals. First born children and animals may have been given preferential access to the grain, therefore making them more susceptible to the harmful effects of such mycotoxins.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Flu: Facts about seasonal influenza and bird flu

What is hantavirus? The rare but deadly respiratory illness spread by rodents