Stone Age woman had modern-looking face

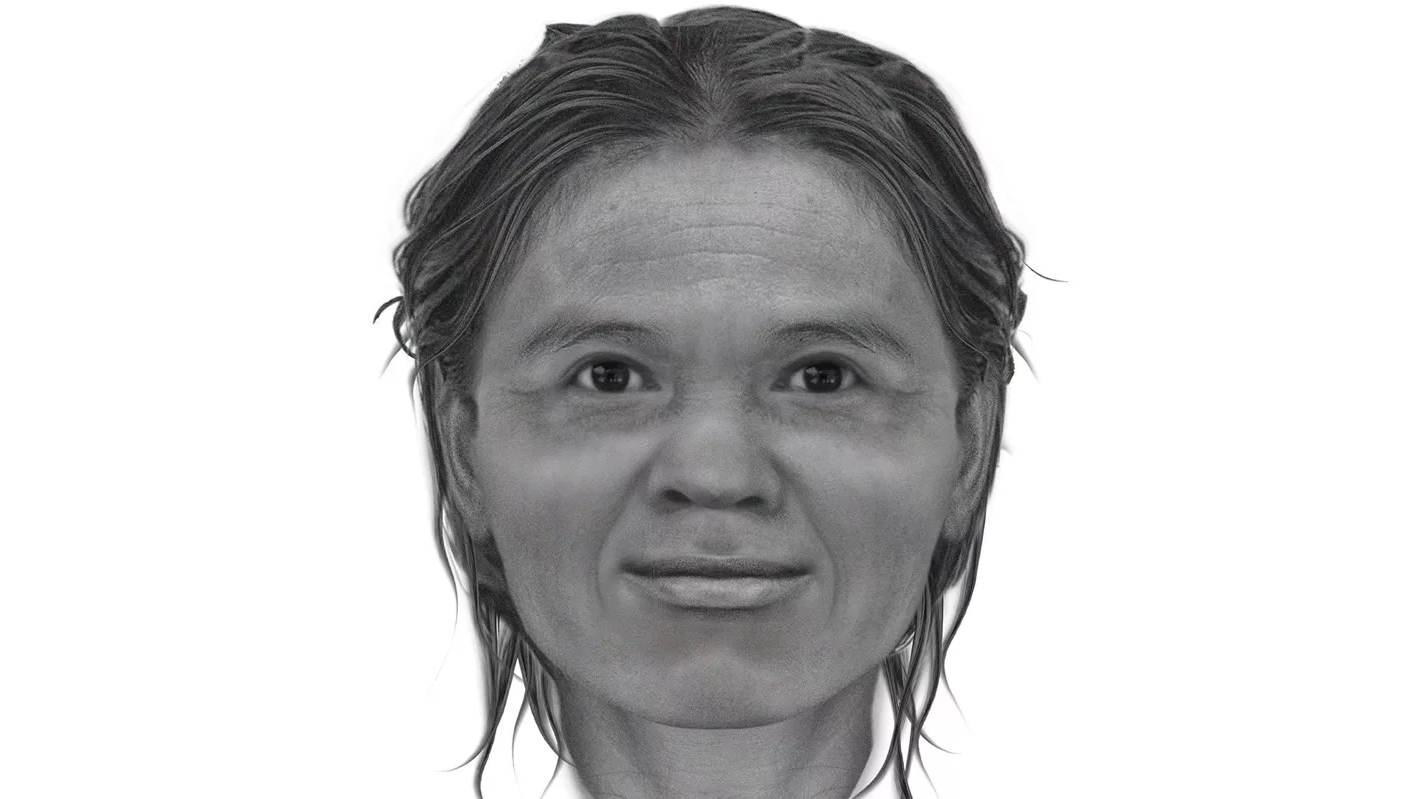

The pretty face of a woman who lived more than 13,000 years ago in what is now Thailand, and is considered a likely descendant of the first humans to populate Southeast Asia, is seeing the light of day.

Scientists have created a digital reconstuction of the woman's face based on skeletal remains found in 2002 in the Tham Lod rock shelter in northwest Thailand. Though fragmented, the remains included the bones of the skull and teeth. [Images: A New Face for Ötzi the Iceman Mummy]

It appears the body was laid to rest on its left side in a flexed position and with a hammerstone (stone used as a hammer) across the forearm.

Above the burial was a circle with five large pebbles and rounded limestone fragments. This could be interpreted as being part of the woman's burial ritual, but that's just speculation, as graves have been shown to be highly variable across the region, the researchers said.

Dating bones

A Thai research team, led by Rasmi Shoocongdej, a professor of archaeology at Silpakorn University in Bangkok, established that the bones belonged to a woman who was probably between 25 and 35 years old and 5 feet tall (152 centimeters).

The team used accelerator mass spectrometry to separate out istotopes of radiocarbon from the sediment where the burial was found. (Isotopes are atoms of the same element that have different numbers of neutrons.) Using the known decay rates of this form of carbon, the scientists estimated that the young woman lived 13,640 years ago during the Late Pleistocene.

This makes the woman "the oldest human burial to be excavated in the northwestern highlands of Thailand, and probably a direct descendent of the founder population of Southeast Asia," Shoocongdej wrote in the academic journal Antiquity.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Finding a face

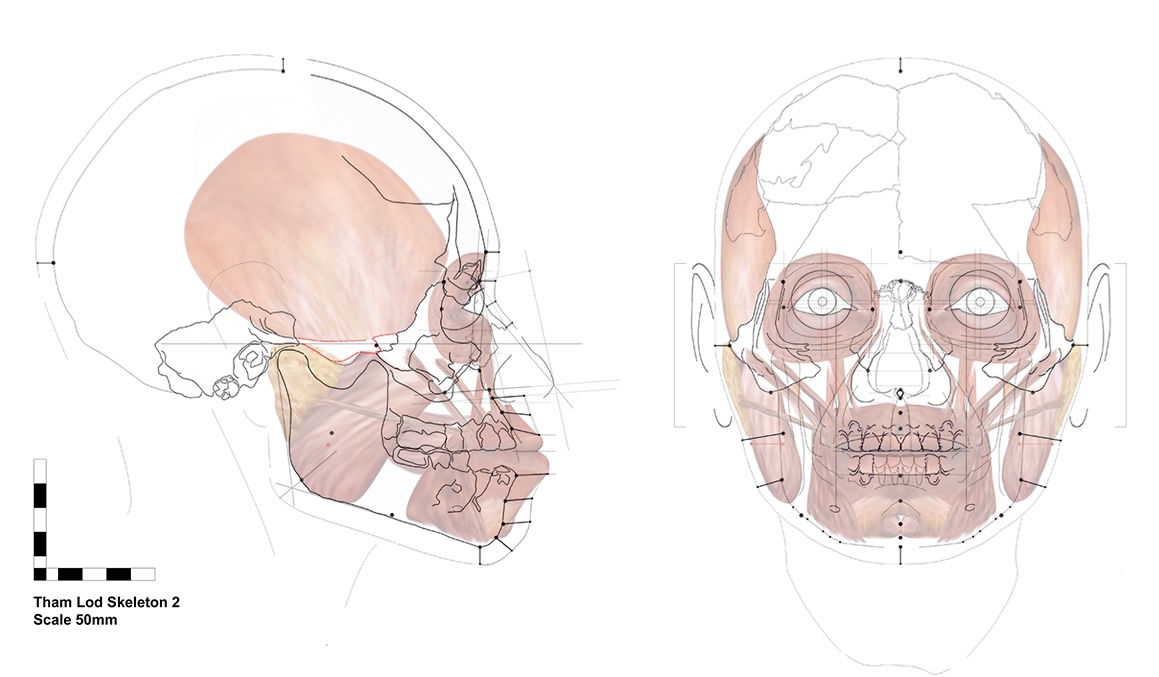

To produce a representation of the woman's face, the Thai-funded research project did not rely on the widely used forensic facial reconstruction method. Instead, they employed a range of robust skull-soft tissue relationships to estimate the individual's facial features.

"Facial reconstruction is a very, very popular method, but it has been tested and found to be scientifically invalid since around 2002," study co-author Susan Hayes, of the University of Wollongong in Australia, told Live Science.

Hayes noted the woman was a perfect candidate to test whether the new methods could reconstruct aspects of the unique facial features of a woman who is neither recent nor European.

To estimate the facial appearance, Hayes used measurements of skulls, muscle, skin and soft facial tissue derived from large samples of contemporary populations worldwide. She then used the data to determine the relationship between the skull and soft tissue measurements and facial features. By applying this relationship to the Thai skeletal remains, Hayes created a two-dimensional image of a good-looking woman with small, almond-shaped eyes and a wide jaw.

"The woman is anatomically modern, so you would anticipate an anatomically modern facial appearance," Hayes said.

Hayes explained that facial reconstructions in museums tend to depict ancient human ancestors in a particular style.

"But this style is not at all supported by the evidence in scientific studies, and instead relates to the pre-Darwinian Christian mythology of the appearance of 'wild men,'" she added.

Stone Age looks

However, the main concern of the study was to make sure the results weren't too biased toward the facial appearance of contemporary women. Indeed, most of the skull-soft tissue relationships used in the study were statistical averages derived from the variation displayed in recent European populations.

"So it was possible that these predominantly recent European relationships might have overwritten the woman's distinctive Late Pleistocene and population characteristics," Hayes said.

Instead, when compared to the facial data derived from 720 contemporary women living in 25 different countries and across three continents, the facial appearance of the Stone Age woman remained clearly distinct, the researchers said. Moreover, it was not influenced by European features, the scientists said. [In Images: Deformed Skulls and Stone Age Tombs from France]

The facial approximation showed a closer connection with women from East and Southeast Asia, and appears affiliated with today's Japanese women in facial width and height, the study said.

Analyses of eyes, nose and mouth also indicated that the Stone Age woman shared morphological similarities with African women, particularly in the dimensions of the nose and mouth, the researchers said.

"Other than a clustering with extant modern Hungarian women with regard to mouth width, European women, despite dominating both the comparative population study and the methods used to estimate facial appearance, are noticeably absent," the researchers said.

Overall, the estimated face retained the distinctive characteristics of Late Pleistocene skulls, such as a larger jaw and more robust features, the researchers said.

The downside to the methods used by the team is that they take longer to achieve than the much quicker, and comparatively simple, method of facial reconstruction, the researchers said.

But, Hayes said, "the dead deserve the best we can do, no matter how long ago they lived, and this includes taking the time to apply the best methods to estimate each unique face from our human past."

Original article on Live Science.