What Drove Tsavo Lions to Eat People? Century-Old Mystery Solved

Their names were "The Ghost" and "The Darkness," and 119 years ago, these two massive, maneless, man-eating lions hunted railway workers in the Tsavo region of Kenya. During a nine-month period in 1898, the lions killed at least 35 people and as many as 135, according to different accounts. And the question of why the lions developed a taste for human flesh remained a subject of much speculation.

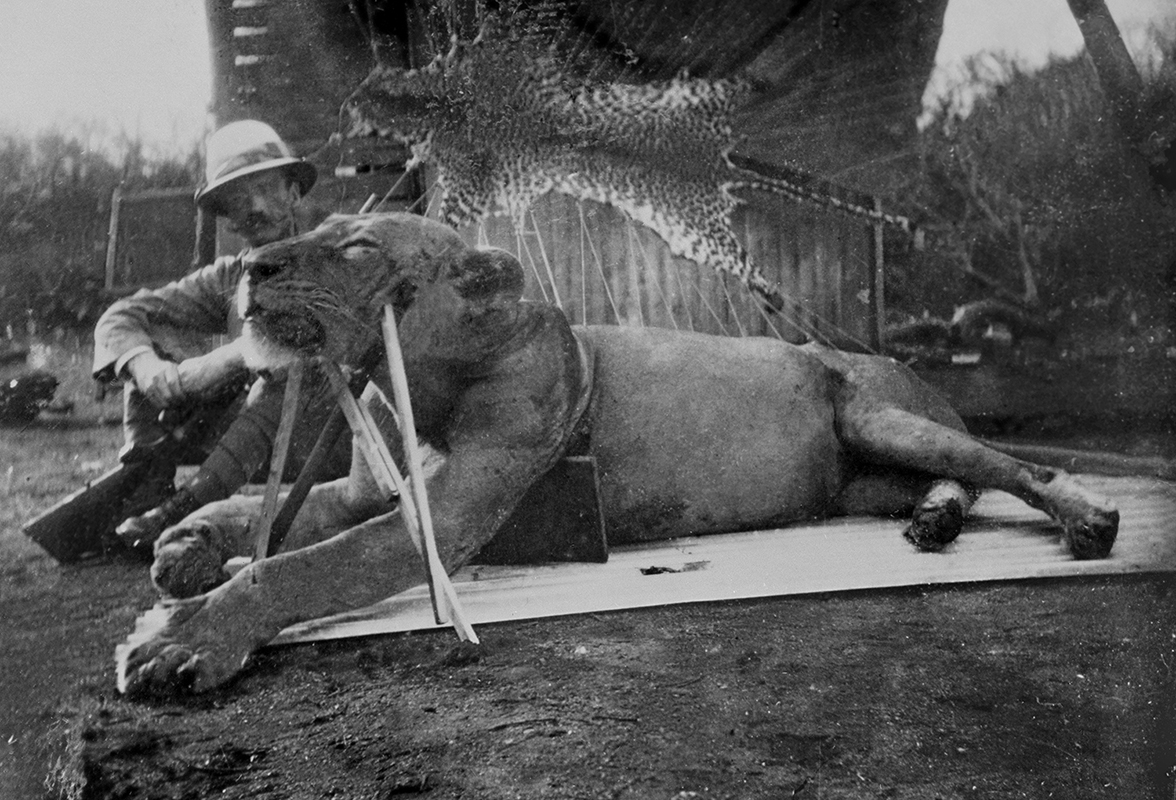

Also known as the Tsavo lions, the pair of beasts ruled the night until they were shot and killed in December 1898 by railway engineer Col. John Henry Patterson. In the decades that followed, audiences were captivated by the story of the ferocious lions, first told in newspaper articles and books (one account was written by Patterson himself in 1907: "The Man-Eaters of Tsavo"), and later in movies.

In the past, it had been suggested that the lions' desperate hunger drove them to eat people. However, a recent analysis of the remains of the two man-eaters, a part of the collection at The Field Museum in Chicago, offers new insight into what led the Tsavo lions to kill and eat people. The findings, described in a new study, suggest a different explanation: that tooth and jaw damage — which would have made it excruciating to hunt their usual large herbivore prey — was to blame. [Photos: The Biggest Lions on Earth]

For most lions, humans are typically far from their first choice of prey. The big cats usually feed on large herbivores, such as zebras, wildebeest and antelope. And rather than viewing people as potential meals, lions tend to go out of their way to avoid humans entirely, study co-author Bruce Patterson, curator of mammals at The Field Museum, told Live Science.

But something else convinced the Tsavo lions that humans were fair game, Patterson said.

To unravel the century-old mystery, the study authors examined evidence of the lions' behavior preserved in their teeth. Microscopic wear patterns can tell scientists about an animal's eating habits — particularly during the last weeks of life — and the Tsavo lions' teeth didn't show signs of the wear and tear associated with crunching big, heavy bones, the scientists wrote in the study.

Hypotheses proposed in the past suggested that the lions developed a taste for people through scavenging, perhaps because their usual prey had died off from drought or disease. But if the lions were hunting humans out of desperation, the starving cats would have certainly cracked human bones to get the last bit of nutrition from their grisly meals, Patterson said. And wear patterns on the teeth showed that they left the bones alone, so the Tsavo lions probably weren't motivated by a lack of more suitable prey, he added.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A more likely explanation is that the ominously named The Ghost and The Darkness began hunting humans because infirmities in their mouths hindered their ability to catch bigger and stronger animals, the study authors wrote.

Down in the mouth

Previous findings, first presented to the American Society of Mammalogists in 2000, according to New Scientist, documented that one of the Tsavo lions was missing three lower incisors, and had a broken canine and a sizable abscess in the tissues surrounding another tooth's root. The second lion also had damage in its mouth, with a fractured upper tooth showing exposed pulp. [The 10 Deadliest Animals on Earth]

For the first lion in particular, pressure on the abscess would have caused unbearable pain, providing more than enough motivation for the animal to skip large, powerful prey and go after punier people, Patterson said. In fact, chemical analysis conducted in another, earlier study, published in 2009 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, showed that the lion with the abscess consumed more human prey than its partner. Moreover, after the first lion was shot and killed in 1898 — more than two weeks before the second lion was gunned down — the attacks on people ceased, Patterson noted.

Nearly 120 years after the man-eaters' lives abruptly ended, fascination with their gruesome habits persists. But had it not been for their preserved remains — which John Patterson sold to FMNH as trophy rugs in 1924 — today's explanations for their habits would be no more than speculation, Bruce Patterson told Live Science.

"There would be no way to resolve these questions if it weren't for specimens," he said. "After almost 120 years, we can tell not only what these lions were eating, but we can resolve differences between these lions by interrogating their skins and skulls.

"There's a lot of science you can build on that, all derived from specimens," Patterson added. "I have 230,000 other specimens in the museum collection, and they all have stories to tell."

The findings were published online today (April 19) in the journal Scientific Reports.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.