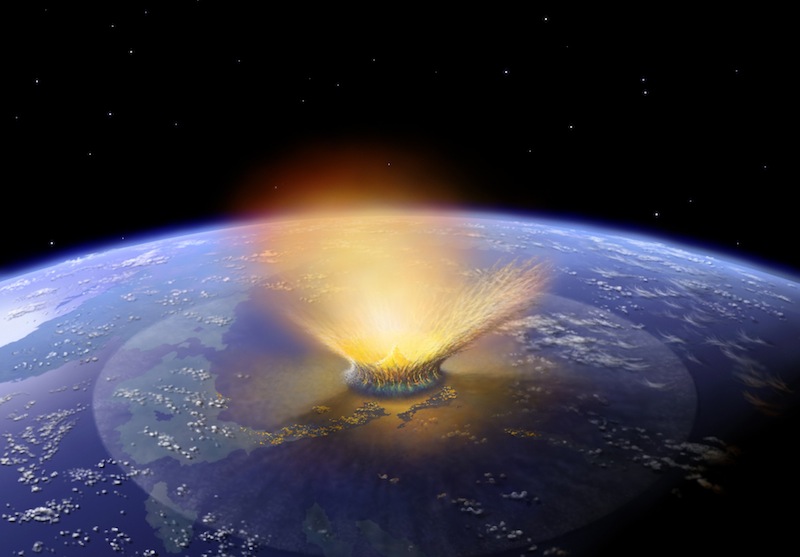

If you live in fear of an asteroid strike, here's some detail to help flesh out your nightmares.

A killer space rock is most likely to get you via violent winds that fling you against something hard or powerful shock waves that rupture your internal organs, according to a new study.

"This is the first study that looks at all seven impact effects generated by hazardous asteroids and estimates which are, in terms of human loss, most severe," lead author Clemens Rumpf, a senior research assistant at the University of Southampton in the United Kingdom, said in a statement. [Potentially Dangerous Asteroids (Images)]

Rumpf and his colleagues simulated 50,000 asteroid strikes around the globe using computer models. These artificial impacts involved space rocks 50 feet to 1,300 feet wide (15 to 400 meters) — the size range that hits Earth most frequently, the scientists said.

Then, the team estimated the percentage of deaths caused by each of the seven effects Rumpf referred to: shock waves, wind blasts, heat, flying debris, cratering, seismic shaking and tsunamis.

Wind and shock waves were the most deadly, together accounting for more than 60 percent of all lives lost. (Though these two effects act in concert, wind blasts were far more devastating than shock waves, the study found.) The sizzling heat of an impact was responsible for nearly 30 percent of deaths, and tsunamis took most of the rest.

Each of the other three effects claimed only a tiny sliver of the death toll, according to the study. Flying debris had a maximum contribution of just 0.91 percent, for example; the figures for cratering and seismic shaking were 0.2 percent and 0.17 percent, respectively.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rumpf and his colleagues also determined that land-based asteroid impacts are about 10 times deadlier than ocean strikes. In addition, they found that space rocks have to be at least 59 feet (18 m) wide to be lethal.

That lower limit is about the size of the object that exploded above the Russian city of Chelyabinsk in February 2013, generating a shock wave that broke countless windows on the ground below. The resulting flying glass shards injured more than 1,000 people but killed nobody.

"This report is a reasonable step forward in trying to understand and come to grips with the hazards posed by asteroids and comet impactors," Jay Melosh, a geophysicist at Purdue University who was not involved in the new study, said in the same statement.

Melosh added that the findings "lead one to appreciate the role of air blasts in asteroid impacts, as we saw in Chelyabinsk."

Astronomers have discovered more than 16,000 near-Earth objects to date. However, that number is just a tiny sliver of the total, which is thought to be in the millions.

Scientists think they've found about 95 percent of the nearby asteroids that could threaten human civilization if they were to hit Earth — behemoths at least 0.6 miles (1 km) wide — and none of these monsters poses a threat for the foreseeable future.

But there are still plenty of dangerous rocks zooming around out there undiscovered. On average, Earth gets hit by an asteroid at least 190 feet (60 m) wide every 1,500 years and by a rock at least 1,300 feet (400 m) wide every 100,000 years, Rumpf said.

"The likelihood of [a serious] asteroid impact is really low," said Rumpf. "But the consequences can be unimaginable."

Researchers around the world are studying ways to prevent asteroid strikes and thereby avoid those consequences. Most incoming space rocks that are detected with decades of lead time could likely be nudged away from Earth using "gravity tractors" and kinetic impactor probes, scientists say. (Gravity tractors would fly alongside a potentially dangerous asteroid for long stretches, whereas kinetic impactors would slam into the space rock.)

But a nuclear bomb may be required to deal with giant asteroids or comets that are discovered just weeks or months before a potential impact.

The new study was published last month in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.