Hunt Kicks Off for 'Teddy Bear' Marsupial and Other 'Lost' Species

A duck with a pink head, a tree-climbing crab, and a monkey with red thighs are among the targets of a new global hunt for "lost" species.

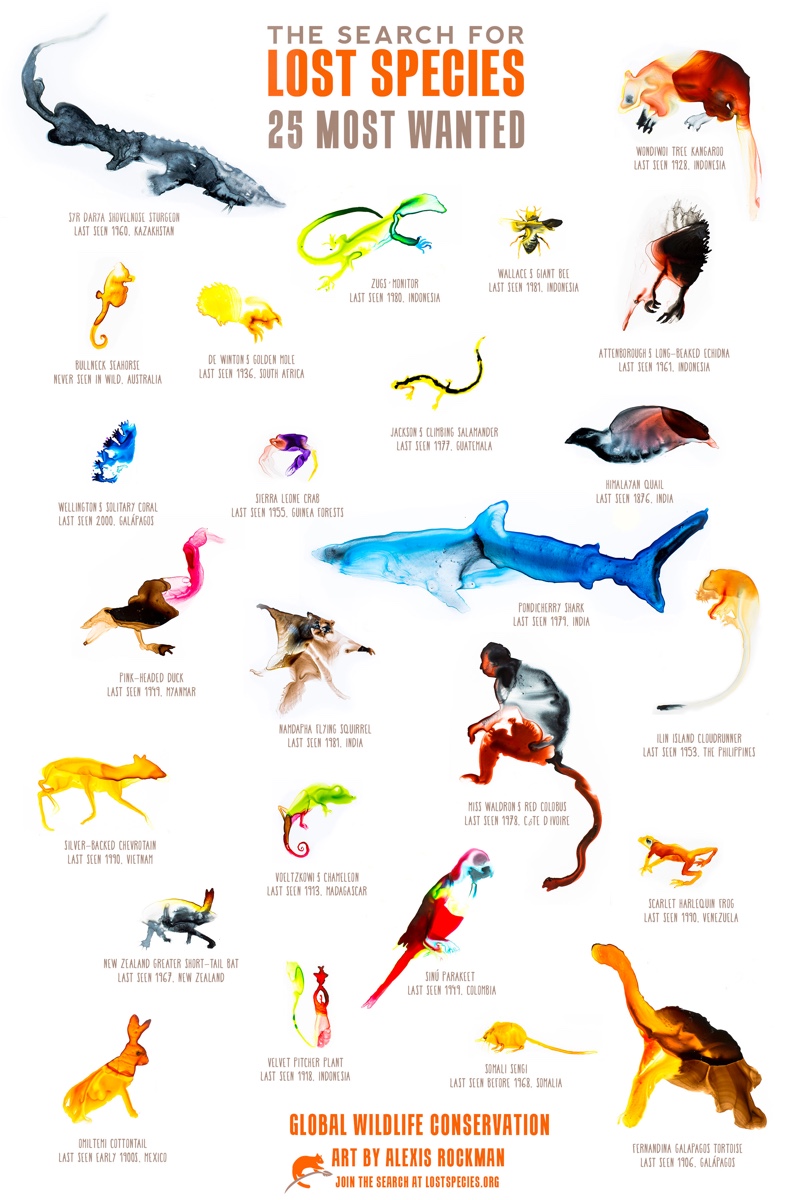

Global Wildlife Conservation (GWC), an organization based in Austin, Texas, with a focus on biodiversity and wildland preservation, has launched a new initiative to search for 25 species that have not been seen for years or decades — or, in the case of the Fernandina Galapagos tortoise, more than a century. The goal is to see if any of the species still survive and, if so, save them.

"While we're not sure how many of our target species we'll be able to find, for many of these forgotten species, this is likely their last chance to be saved from extinction," GWC spokesperson Robin Moore said in a statement. [10 Extinct Giants That Once Roamed North America]

Lost but not forgotten

The group is focusing on species that have not been seen since at least 2007. Collaborating with the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), GWC actually came up with a list of 1,200 "lost" species but chose the charismatic creatures with decent chances of being saved, if they can be found.

On the list is the Syr-darya shovelnose sturgeon (Pseudoscaphirhynchus fedtschenkoi), a fish once found only in the Syr Darya river of Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan that has not been seen since the 1960s. Both the silvery Zug's monitor (Varanus zugorum) and the Wallace's giant bee (Megachile pluto), the latter of which is considered the world's largest bee, have been missing from Indonesia since the early 1980s. Another lost denizen of Indonesia is the Wondiwoi tree kangaroo (Dendrolagus mayri), a teddy-bear-faced marsupial missing since 1928.

Also on the most-wanted list are the Sierra Leone crab, a freshwater, tree-climbing crustacean not seen since 1955; the elusive Pondicherry shark (Carcharhinus hemiodon), not seen in its Indo-Pacific coastal habitat since the late 1970s; and the riotously colored Sinu parakeet, missing from Colombia since 1949.

Scientists will also be searching for the pink-headed duck (Rhodonessa caryophyllacea) — a brown diving duck with a distinctive pink head and neck. The species was last seen in 1949 in Myanmar. They'll also hunt in the Ivory Coast for Miss Waldron's red colobus (Piliocolobus waldronae), a monkey known for the scarlet fur on its thighs and forehead, which has not been seen since 1978.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hope for the missing

Some species on the list threaten to slip out of living memory. The Fernandina Galapagos tortoise lived on Fernandina, the least-disturbed island in the Galapagos archipelago. The first specimen was collected in 1906, and the turtle hasn't been seen since.

Missing doesn't mean extinct, however. The Omilteme cottontail rabbit (Sylvilagus insonus) from Guerrero, Mexico — one of the top 25 animals on the wanted list — disappeared from humanity's radar soon after its discovery in 1904. In 1998, however, researchers went looking and found two dead specimens. Now, GWC hopes to find living examples of the shy rabbits.

One species on the list has never been seen in the wild. Hippocampus minotaur, the bullneck seahorse, is known from four museum specimens collected between 1927 and 1981, according to the IUCN. No one knows anything about its behavior in the wild, its habitat or its population numbers.

The Search for Lost Species project is currently in the fundraising phase, with a goal of launching expeditions by the fall. More information can be found at lostspecies.org.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.