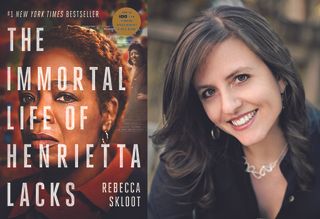

'The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks': Q&A with Author Rebecca Skloot

The original HBO movie "The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks," based on the nonfiction book by journalist Rebecca Skloot and starring Oprah Winfrey as Deborah Lacks, Henrietta's youngest daughter, premieres tomorrow (April 22) at 8 p.m. (local time). While the film will certainly introduce Lacks' story to a wider audience, the medical research community is already well-acquainted with her "immortal" cells, which have contributed to important discoveries for over half a century.

Lacks, an African-American woman born in Roanoke, Virginia, in 1920, was diagnosed with cervical cancer in 1951, and cells sampled from one of her tumors astonished scientists by reproducing indefinitely in the lab — something that no other cells were known to do.

Her unusual cells formed what became known as the HeLa cell line; after she died, they were widely distributed within the scientific community — without her family's knowledge — and were instrumental in groundbreaking biomedical research, contributing to the discovery of the polio vaccine and to treatments for cancer. But for decades, even as Lacks' children and loved ones mourned her death, they were unaware that some of her cells lived on, and didn’t know that her cells were being used in medical research. [HBO Unveils Trailer for 'The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks']

Skloot began investigating Lacks' story in 1999 as a graduate student, following the trail blazed by HeLa cells through modern medicine. She uncovered previously unexplored details about Lacks' life, and revealed how Lacks' family was affected by her death — and by the discovery years later of the HeLa cell line.

Recently, Skloot spoke with Live Science about her involvement with the HBO film adaptation and about Lacks’ enduring story, which — like her unusual cells — appears to have a life of its own.

This Q&A has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Live Science: What was your role in the process of adapting your book to the HBO movie?

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Rebecca Skloot: I'm a consultant on the film — so are some of the members of the Lacks family — and I've been involved from the beginning. I've read drafts of the script, offered feedback on it as it evolved, helped with research and developing characters along the way.

One of the reasons I was comfortable doing the movie with HBO in the first place was they were open to having me and the family involved. I thought it was really important that the story stick as close to the facts as possible without being overly fictionalized. Part of the story of Henrietta and her family is the misinformation that was put into world — with the family not involved, her name incorrect, various stories that weren't true. I didn't want the movie to add to that, to fictionalize in a way that would add to lack of clarity about who she was and what her legacy was.

HBO really wanted to get it right. We talked with actors — several members of the family and I spent time with Oprah. I provided audio tapes from my research process so the actors could listen to characters for their scenes. And during filming, me and over one dozen Lacks' family members visited various locations on set, and they would let us watch.

Live Science: Are there parts of Henrietta's story that emerge more clearly in the film, because it's a more visual medium?

Skloot: There are things movies can do that books can't do, and vice versa. There's a lot in the book that couldn't be in the film — I had 400 pages to flesh out the whole story — but the things you can show on a page are definitely different than what you can show on the screen.

One thing about film is how much can be conveyed in a split second between two characters where nothing is said — or just a facial expression on a really good actor — and the emotions that can evoke. There are things in a movie that visually would convey a very powerful message, that would take me many pages to convey in a book, and would feel very different. I didn't want the movie to be a Cliffs Notes version of the book — my hope was that it would be a companion piece, that it and the book would exist in a way that added to each other. And together, they paint this really rich picture.

Live Science: Did you see yourself as a character in the story when you were writing it, and did that change when you became involved with the film adaptation?

Skloot: I was very resistant to putting myself in the book at all! Eventually I realized that the book is about a lot of different things, and one of them is the ethics of journalism and telling people's stories. In the book, I tell the history of all the other journalists who came along, and the impact that their reporting had on the family — and in doing that I realized it would be dishonest if I left myself out.

And I very intentionally left out everything personal about myself — I was just "Rebecca the reporter," so it's a very one-dimensional character. In the movie that doesn't work — a character can't be one-dimensional in a movie. That's one of the places where I think the movie does add quite a bit. It's really showing what does it mean to have a white reporter and a black woman who is being written about — what does it mean that the reporter is white, how does that play out? In the course of working on the book, I really saw that I was privileged, that I could walk into a room and ask questions in ways that didn't exist for Deborah [Henrietta Lacks' daughter].

That taught me about race in America. You can see that in the movie, you can see gears clicking in "Rebecca's" head, and you can see her putting the pieces together about race without saying anything about it; it's a really good visualization of something that is an undercurrent in the book.

There are really important stories that have been untold that relate to race in this country that need to be told. And in doing so, they show how we got to where we are today, and that telling stories is an important part of moving forward — acknowledging the past and what's happened, and moving forward from that.

Live Science: What are the biggest challenges for telling science stories, and what makes people sit up and pay attention?

Skloot: I think it's the same challenge as telling any story — you have to make it clear what stakes there are, and there has to be tension and characters. And the added challenge is that you have to explain the science clearly. Showing science is the best way to get people to learn it, but it's also very hard. There are some scenes in the book where Deborah's learning about science from a scientist or from something happening around her, and those are the places where I tried to infuse the actual scientific information. My goal is that people get to the end of the scene, and they go, "Oh my god, I learned something about DNA, but I don't really know where I did that."

Live Science: The question "Who was Henrietta Lacks?" resonated with you long before you started writing her story. Nearly 20 years later, are there still any lingering questions that you have?

Skloot: The movie feels like an important moment of closure for me, the last thing that I felt needed to happen.

A lot of Henrietta was lost to history; there were such few traces of her. I spent years dreaming of finding a trunkful of letters from her, and none of that existed. I was able to build that into the book — I think you get a sense of who she was as a person, but of course there's a side of me that said, "If only I could have sat down with her for 20 minutes." Given what information existed, that's a closed chapter. I'm very excited to see the Lacks family taking the story forward. It's their story, they should be carrying it into the future.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.

Most Popular