Sea Urchins Launch Their Weird Mobile Jaws to Scare Predators

A common and colorful sea urchin has some truly bizarre appendages that seem to move independently from its body, and now scientists know why: It shoots these tiny, venomous jaws into the water to deter predators.

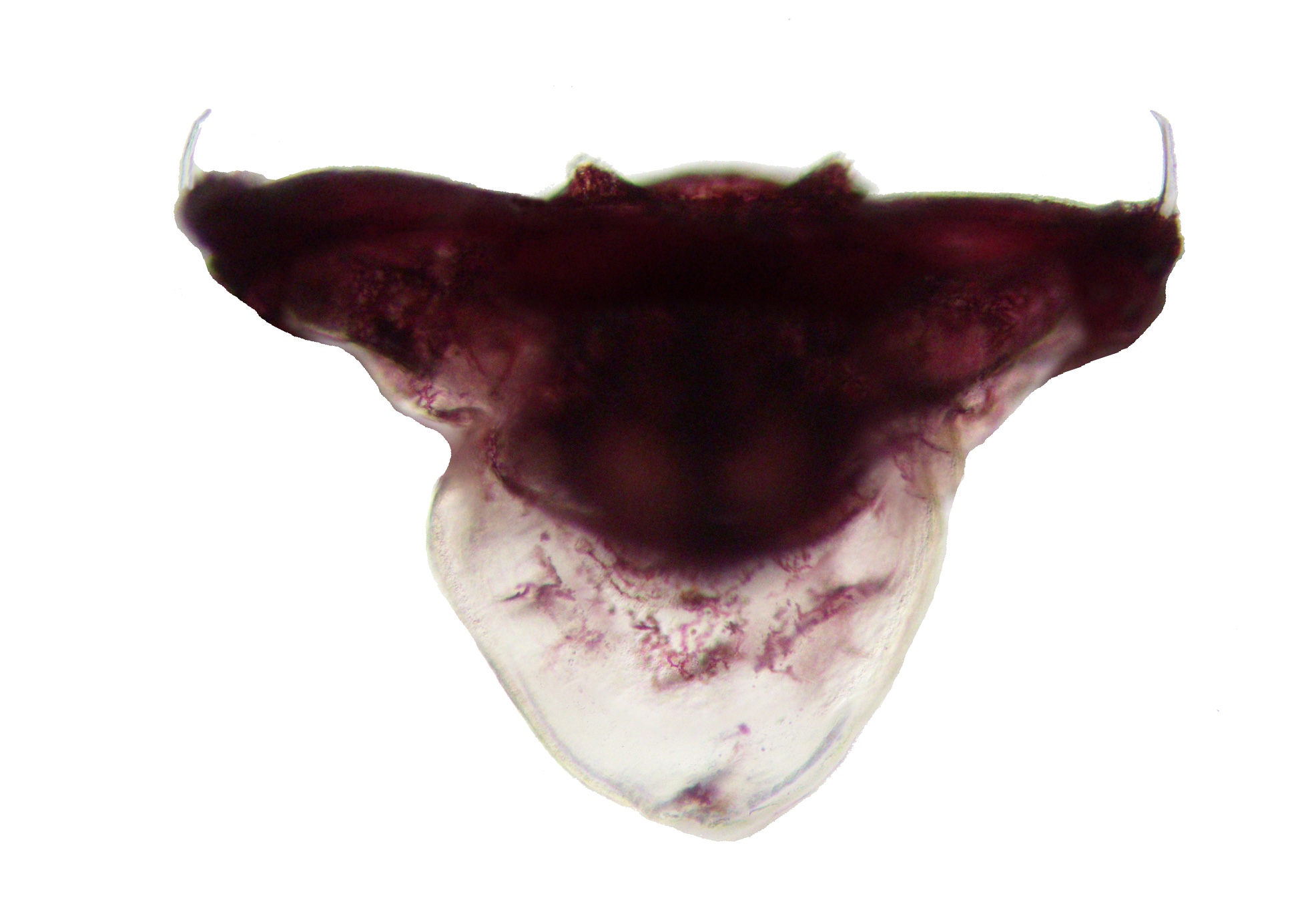

These teensy, toothy jaws are called pedicellariae, and when scientists discovered them in the early 1800s, they thought the jaws were parasites because they seemed to move independently from the urchin. Now, researchers find that urchins use their pedicellariae not only to defend themselves when attacked, but also as a warning to fish and other sea creatures to "stay away!"

Tripneustes gratilla, otherwise known as the collector urchin, is a widespread species found in shallow waters in the Bahamas, the Indo-Pacific region and even the Red Sea. [Gallery: See Photos of Glorious Sea Urchins]

Cloud defense

Pedicellariae are found only in echinoderms, particularly sea stars and sea urchins. The type found on collector urchins are known as globiferous, meaning they have a three-pronged jaw and a venom sac at the end of a long stalk. When disturbed, the urchins shoot a cloud of pedicellariae into the water around their bodies. Those that meet their mark sink their tiny, venomous teeth into the predator's skin. Even if a predator fish tears away the structure in its haste to flee, the jaws remain embedded, and the venom sac keeps pumping irritating toxins into the fish's flesh.

What Sheppard Brennand and her colleagues discovered was that fish don't have to make direct contact with sea urchins to be shot with pedicellariae. To prompt T. gratilla to shoot off these structures, the researchers poked the sea urchins with forceps in a lab for 30 seconds, to simulate predation. Then, they incorporated pedicellariae into squid snacks and offered them to two species of fish that prey on urchins: the black axil chromis (Chromis atripectoralis) and the stocky anthias (Pseudanthias hypselosoma). In an aquarium setting, the fish ate 50 percent fewer treats containing venomous pedicellariae compared with treats containing no pedicellariae. When the researchers washed the pedicellariae of their venom, the fish readily accepted between 80 percent and 90 percent of the squid snacks embedded with tiny jaws, compared with fewer than 20 percent of the treats if the venom wasn't rinsed.

The researchers also tested their squid snacks in the wild at Coffs Harbour Marina, between Sydney and Brisbane, using a GoPro camera to record video of fish behavior around the treats. Again, the fish avoided the pedicellariae-filled food and gravitated toward the clean options.

Unpalatable pedicellariae

Clearly, pedicellariae were unpalatable, Sheppard Brennand said. Next, the researchers put fish in a tank with two flumes, one of which had a sea urchin about 28 inches (72 centimeters) upstream. When the sea urchins were prodded to release their pedicellariae, the fish tended to avoid being downstream, the researchers found. Fish spent less than half of their time in a flume filled with pedicellariae, compared with 70 percent of their time in flumes with an undisturbed urchin or no urchin at all.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Discovering that the pedicellariae cloud deterred fish was the most exciting finding," Sheppard Brennand said. "We had hypothesized that this might be the case, but until you actually do the research and examine the data, you don't know what the outcome will be."

Deterring predators with a long-range defense may save the urchins a lot of wear and tear, since they don't necessarily have to be bitten by every fish that needs to learn to stay away, the researchers wrote. Lots of animals have "pursuit-deterrent" signals like this that don't require contact with predators. Porcupines have their quills, for example, and some species of spider kick off tiny, irritating hairs. Bombardier beetles spray hot, irritating chemicals. And urchins, it seems, have their mobile bite.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.