How Dolphins Do It in Water…with Weird, Complex Genitalia

Being a scientist can be a strange job. Like on the days when your work involves inserting the artificially inflated penis of a dead dolphin into the recently thawed vagina of another dead dolphin, all inside a CT scanner.

For new research presented yesterday (April 23) at the annual meeting of the American Association of Anatomists in Chicago, scientists did just that in the pursuit of a better understanding of how male and female anatomy co-evolve.

"A fair bit is known about male reproductive organs," said Dara Orbach, a postdoctoral fellow at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia and a research assistant at Mount Holyoke College in Massachusetts. "There has been fairly little research on female genitalia, comparatively." [Top 10 Swingers of the Animal Kingdom]

Sex and death

More recently, Orbach said, scientists have increasingly come to realize that the penis is only half the story. A new field focused on "copulatory fit" — how the genitals fit together and influence each other's evolution — has sprung up. But most of the research has been on small insects and other arthropods, which are easy to study because scientists can flash-freeze them in liquid nitrogen while the bugs are mating.

That is "totally not feasible for larger animals," Orbach told Live Science.

Marine mammals in particular are known for their twisty, curvy vaginas. Whales, dolphins and other marine mammals also have to manage sex while floating in water, and they have to keep seawater out of the uterus. Orbach and her colleagues wanted to understand how seals, porpoises and whales pull it off.

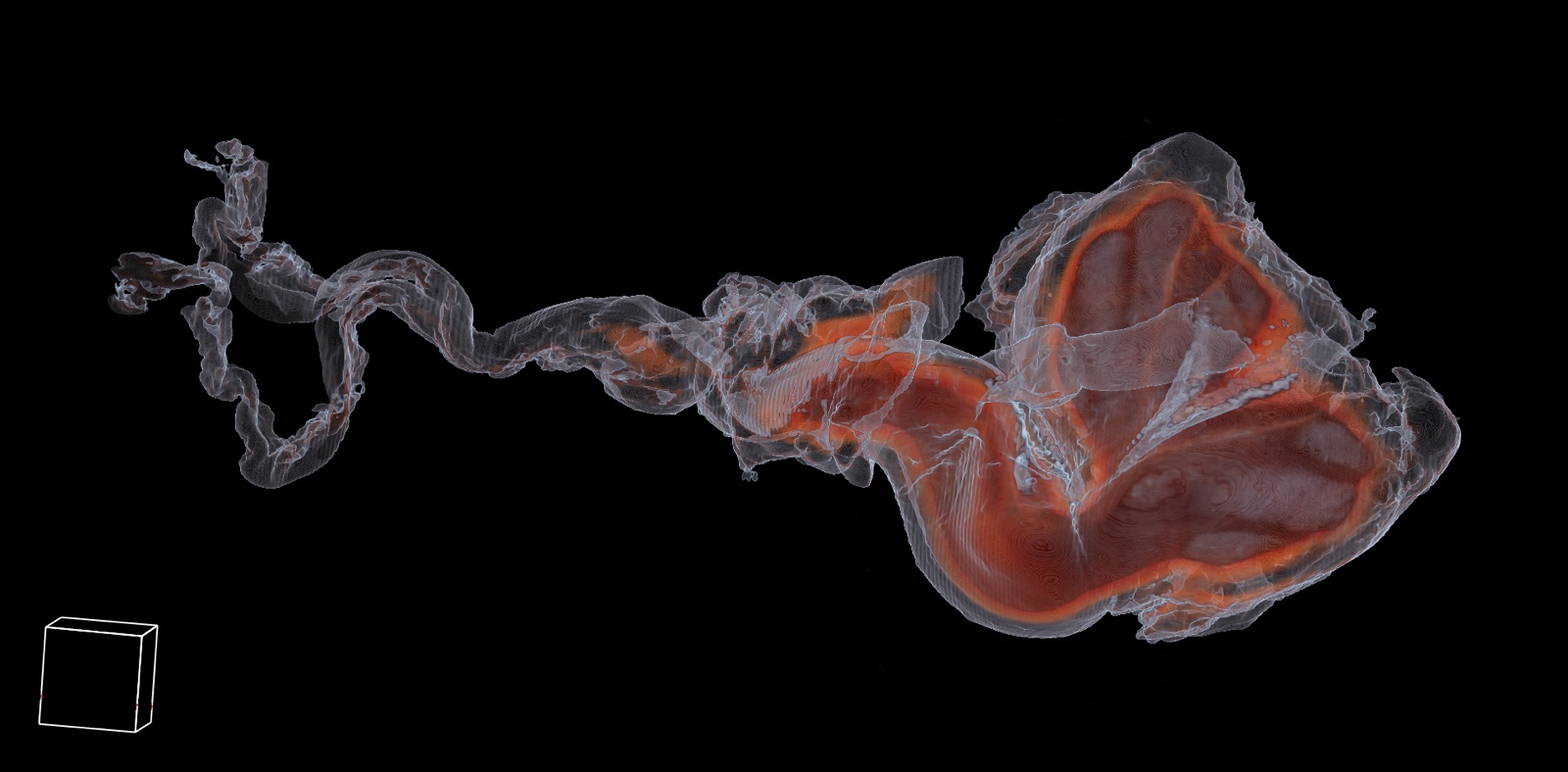

The researchers removed the reproductive tracts from bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncates), common dolphins (Delphinus delphis), harbor porpoises (Phocoena phocoena) and harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) that had died of natural causes. They created molds of the vaginas with silicon so they could understand its shape. Then, they froze the actual vaginal tissue and thawed and stained it with iodine right before their experiments. The penises were pumped full of saline using a nitrogen air pump and then put in formalin to "fix" them in the erect position. The penis was then inserted inside the thawed vaginas. Both sets of genitals were then scanned with computed tomography (CT) the researchers could see how they fit together.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A good fit

The researchers revealed their findings only for the bottlenose dolphins at the Chicago conference; the research has yet to be published, Orbach said, so they are not yet making their full results public. But the images revealed that the bottlenose dolphin penis has to navigate around the female's vaginal fold for successful insemination, Orbach and her colleague, Patricia Brennan, of Mount Holyoke College reported. Diane Kelly of the University of Massachusetts Amherst and Mauricio Solano of Tufts University also collaborated on the work.

"We think that the positioning of the bodies of the males and females are hugely important in terms of the amount of fertilization success," Orbach said. A female might be able to influence whether a male inseminates her simply by shifting her body position slightly so that his penis doesn't penetrate beyond the labyrinthine curves of her vagina.

Some species appear to be more cooperative than others, anatomically speaking, Orbach said. The shape of the vagina, and thus the ease of copulation, varies dramatically between the animals studied.

"What was surprising is it seems that in some of the species it seems to be more competitive, while in other species it seems to be more collaborative," Orbach said.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.