Photos: Gorgeous Landscapes Hidden Beneath Polar Seas

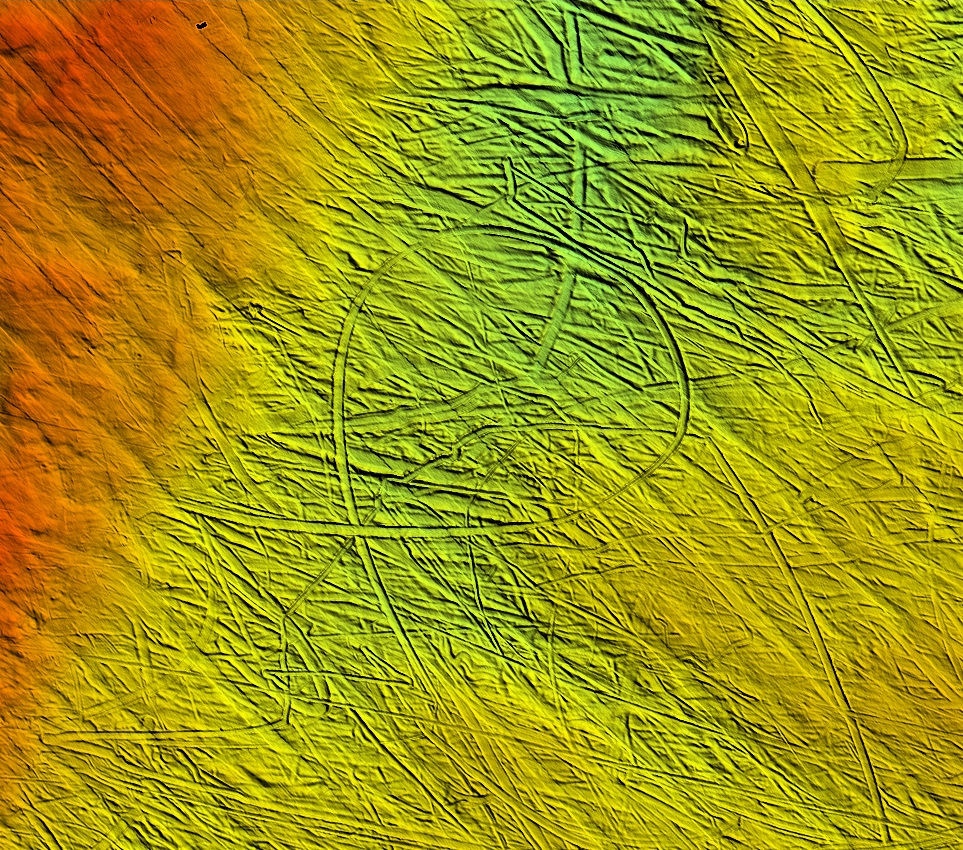

Drumlins

Scientists have compiled an updated atlas of undersea landscapes carved by glaciers and icebergs. These formations, hidden in Earth's polar regions, were captured in 3D by acoustic methods like multibeam echo sounding. [Read the full story here]

Here, 3D seafloor images from the Gulf of Bothnia, between modern-day Finland and Sweden, show a field of drumlins, or egg-shaped hills, in line with the past ice flow direction. Some of these hills rise up to 98 feet (30 meters) above the seabed. (Darker colors indicate greater depths.) Scientists believe that ice moving south toward a large glacier in the Baltic Sea created these hills during the last glacial period about 20,000 years ago.

Iceberg etchings

When the bottom of a massive iceberg touches down on the seafloor and drags through the sediment, it can leave behind strange etchings. This image from south of Brasvelbreen, Svalbard, shows water depths of about 82 feet (25 meters) in red, and 164 feet (50 meters) in green.

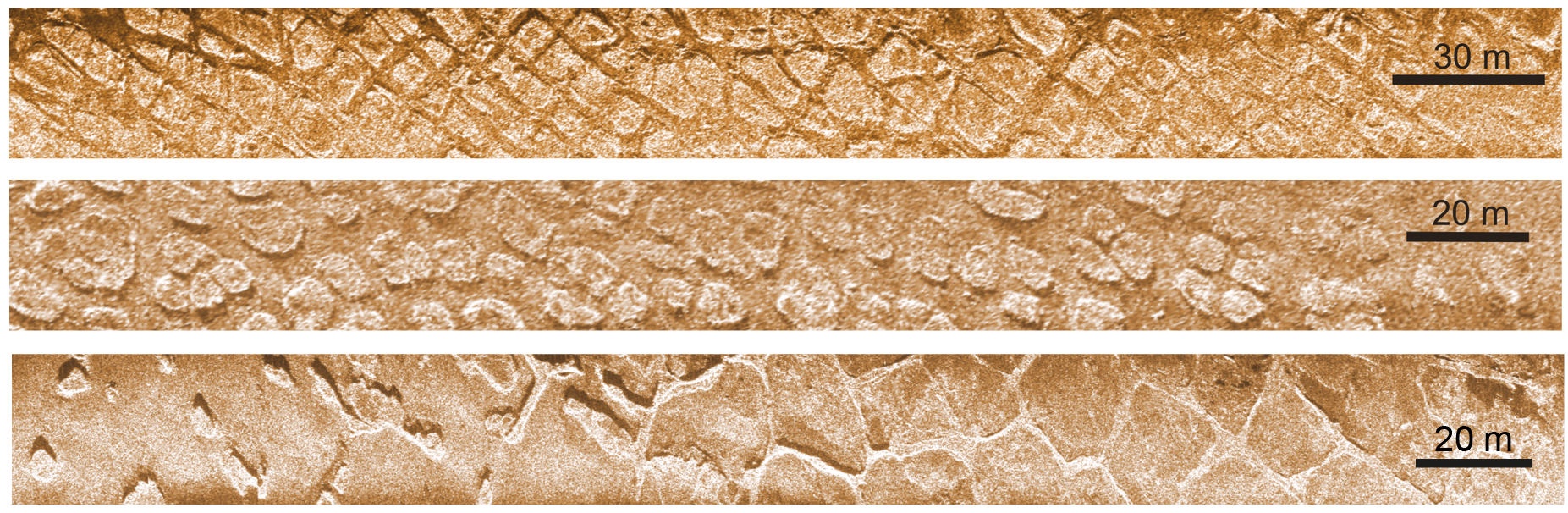

Cracked permafrost

These polygon patterns are submerged in water as shallow as 33 feet (10 meters) in Eastern Siberia's Laptev Sea. The area used to be an exposed permafrost field, and the geometric patterns were created by temperature changes that caused the earth to expand and contract. When sea levels rose about 7,000 years ago, the features were preserved underwater.

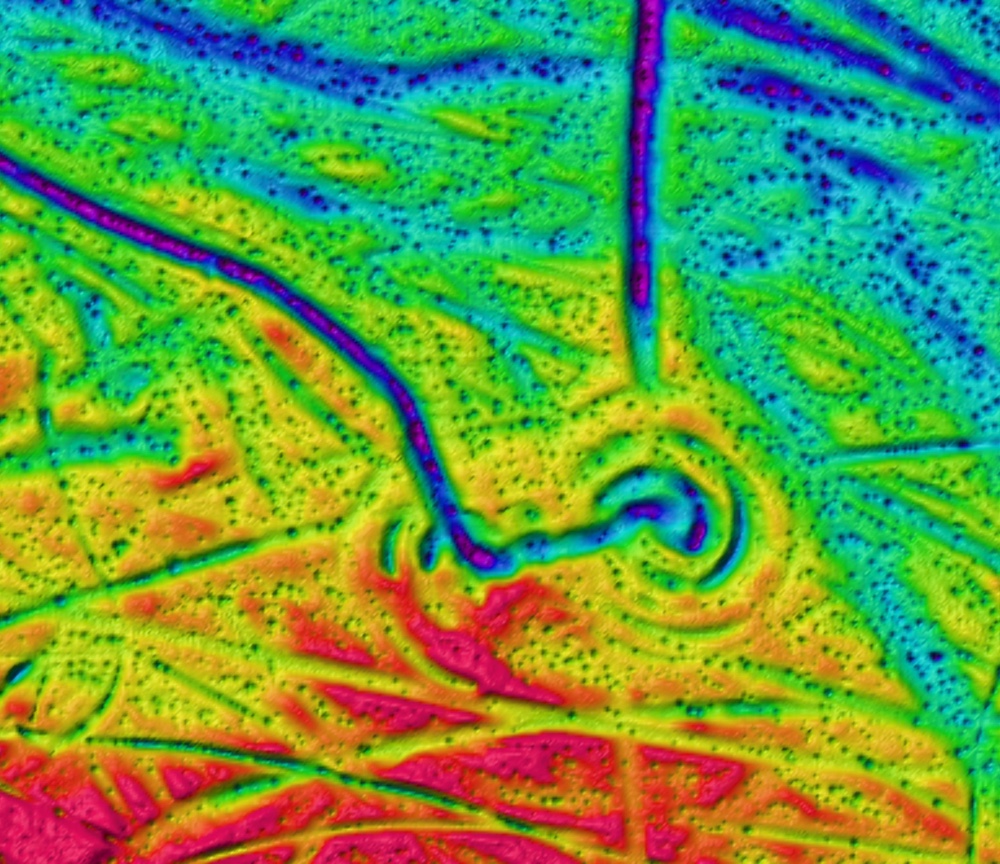

Ploughing the sea

This twirly plough mark was likely left by a rotating iceberg in the central Barents Sea.

Underwater art

These plough marks in the central Barents Sea are very shallow — only a few meters deep — but they are very wide. This means they were likely formed by huge flat-bottomed floating icebergs, bigger than the ones floating in the Arctic today.

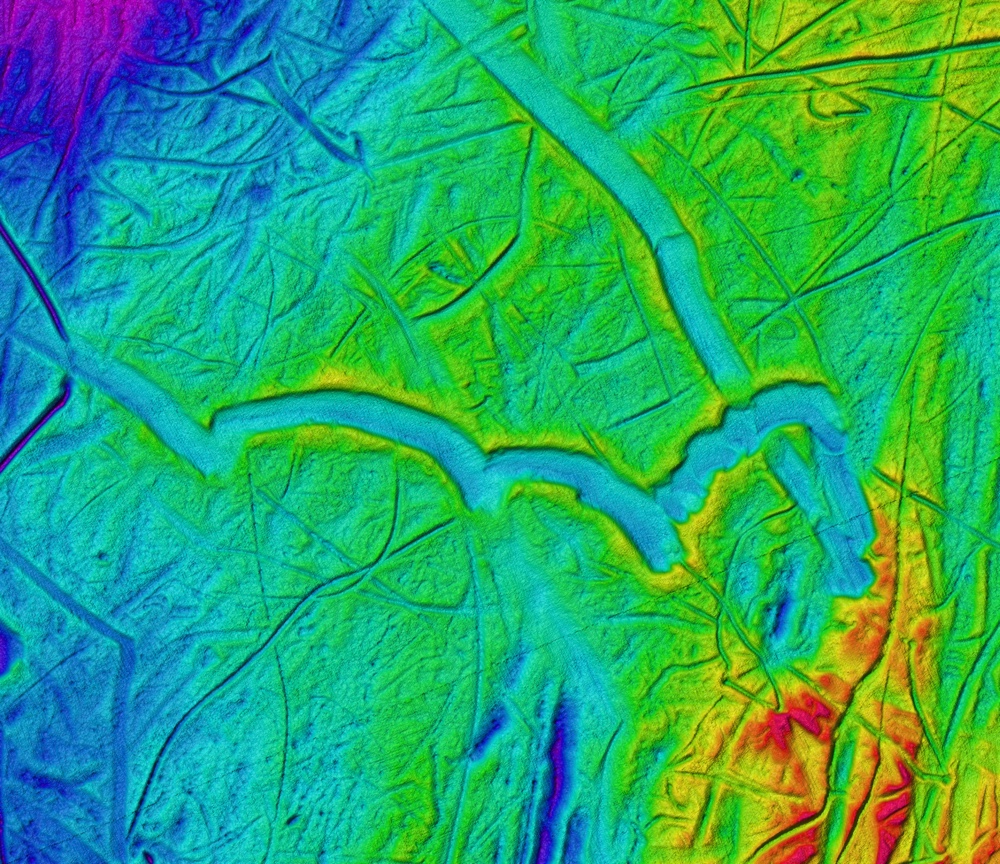

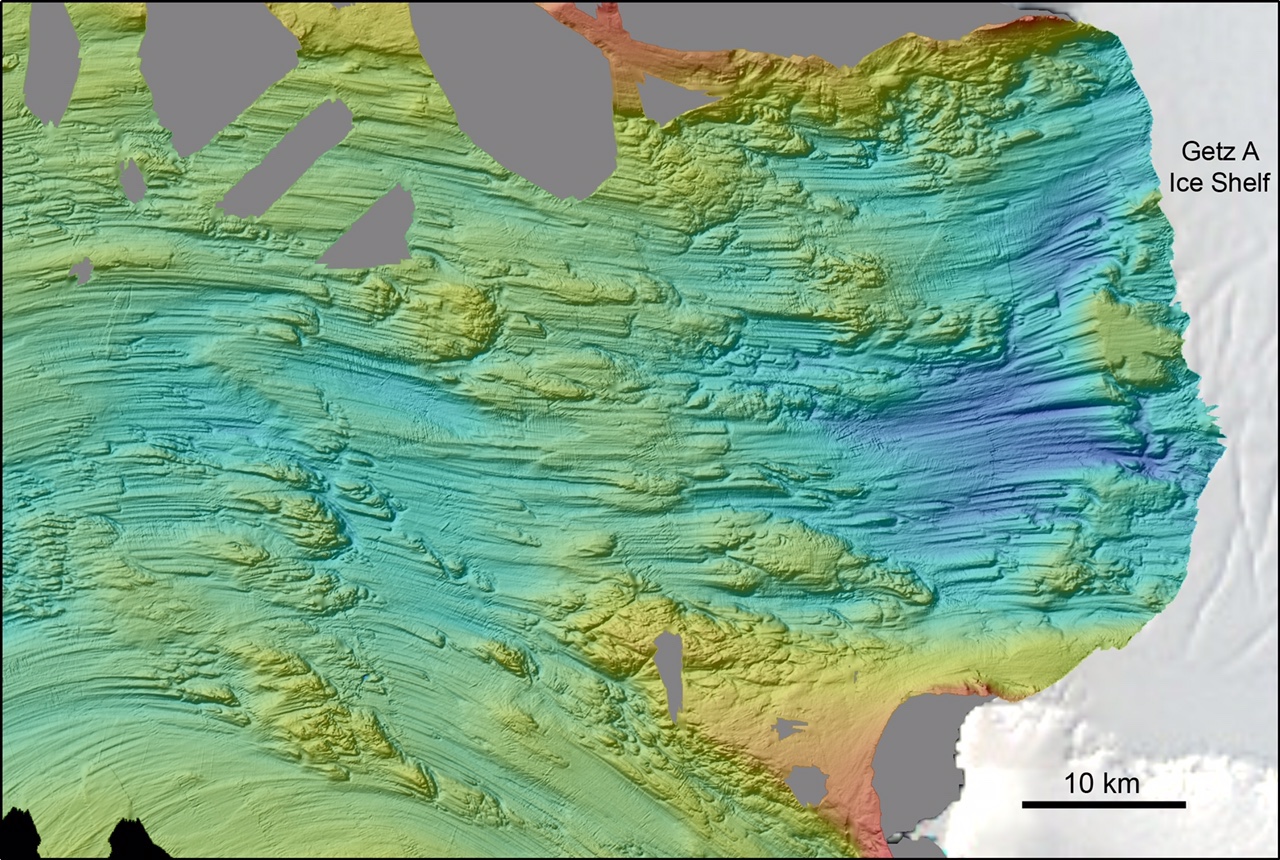

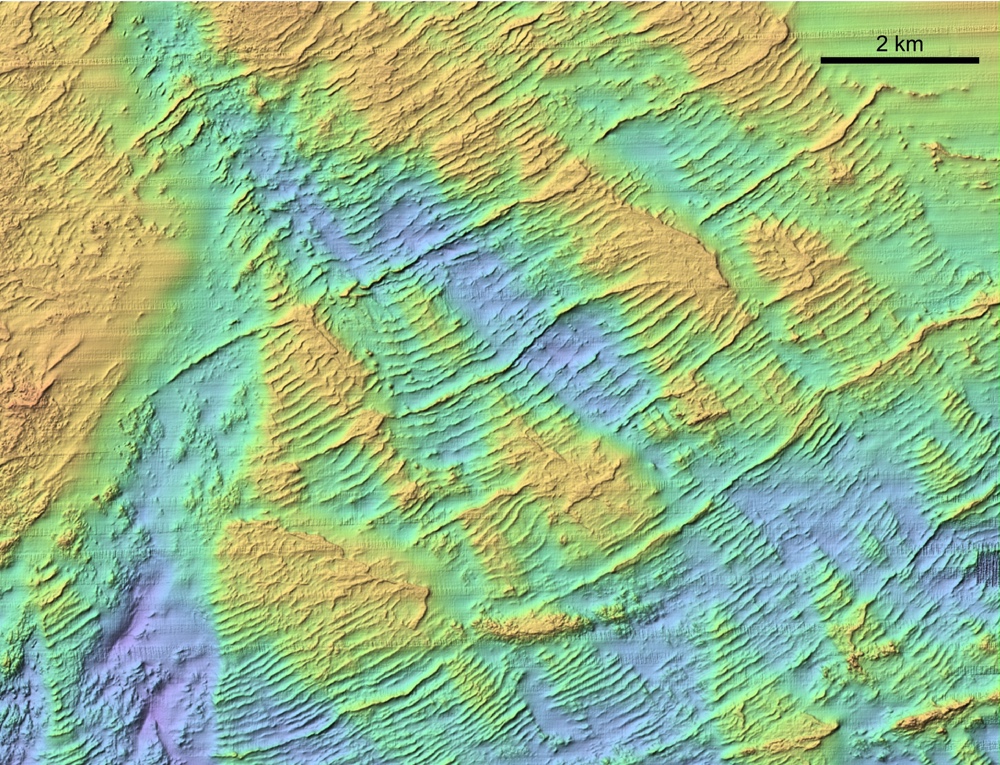

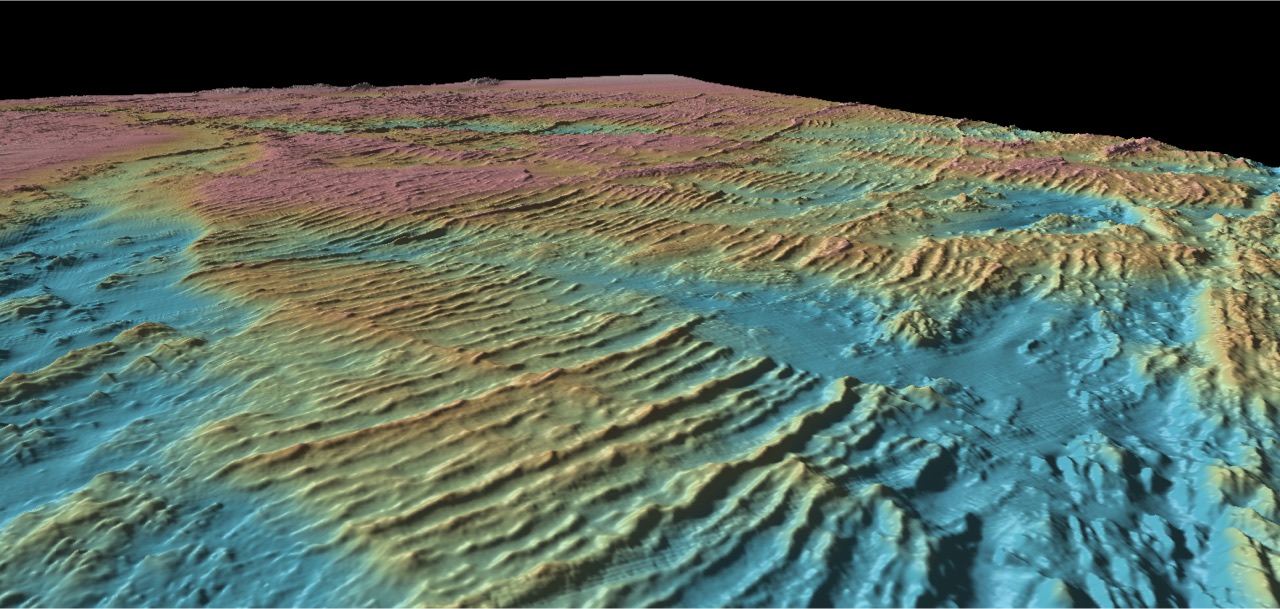

Carved by ice

Fast-flowing ice (moving right to left in this image) carved these streamlined landforms just off the Getz A Ice Shelf in West Antarctica during glacial cold periods in the past. Dark blue represents the deepest areas, at nearly 5,000 feet (1,500 meters) deep.

Seafloor ridges

3D imagery shows the seafloor on the Scotian Shelf off the Atlantic coast of Canada. These ridges, known as moraines, were pushed up when retreating ice margin stabilized, or even briefly advanced again.

Glacial footprints

Another view of the moraine field on the Scotian Shelf looks towards eastern Canada. Scientists hope that by studying the footprints of past glaciers and ice sheets, they’ll be able to predict how ice will behave in a changing climate.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.