Russia from Above: A Glimpse at a Vast Landscape

Olympic Feat

And now for something more upbeat. This is a view of the 2014 Winter Olympics village in Sochi, Russia, captured by the satellite company DigitalGlobe. The image is from Jan. 2, 2014, shortly before the games began.

Natural Beauty

Snow and rock frame picturesque Lake Teletskoye in this astronaut photograph taken in December 2003. The lake is among the deepest in the world, plunging 1,066 feet (325 meters) in places. It sits among the Altay Mountains in Siberia and is both a nature reserve and the site of a research station for Russia's Institute of Taxonomy and Ecology of Animals.

Spikes on the Steppe

The astronauts who snapped this picture from the International Space Station were at first stumped at the strange "spiked" pattern they were seeing on the Kulunda Steppe. The answer turns out to be "topography." The darker areas are lower-lying, forested regions sitting among lighter-colored agricultural fields, according to NASA's Earth Observatory.

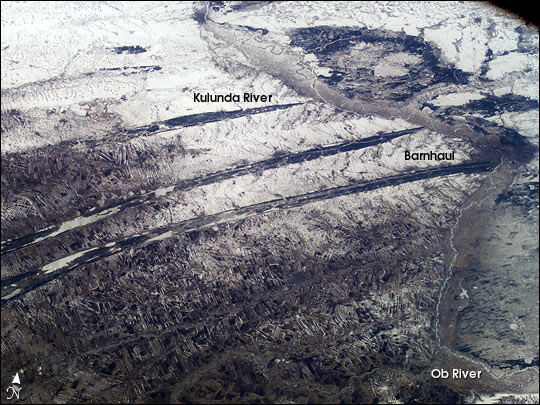

A Winter's Day

A winter's view of the same Kulunda Steppe spikes. The Ob River is visible winding along the right side of this astronaut photograph, which was taken in April 2003. Barnaul, a million-person metropolis, is a dark splotch in the middle right of the picture, sprawling alongside the Ob.

Blue Lagoon

Readjust your eyes: Water appears brownish-orange and land a deep blue in this astronaut photograph of Kaliningrad on the Baltic Sea. The city sits on the Vistula Lagoon, which is separated from the Baltic by a sand spit. Toward the top of the photograph, another sand spit separates the sea from Kurshsky Bay. Sunglint off the water creates a mirror-like effect.

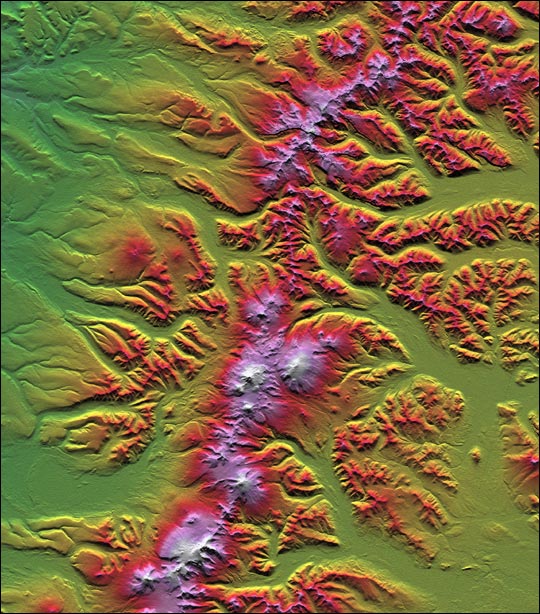

Colorful Kamchatka

The Kamchatka Peninsula stands out in wild color in this visualization made from an instrument that flew aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavour in 2000. The mountains seen in white, pink and red here are the Sredinny Khrebet range. Most of the peaks are volcanos, many of which sport glaciers flowing down their slopes. The glaciers cut steep valleys, which are periodically filled in with volcanic ash and lava, according to Earth Observatory.

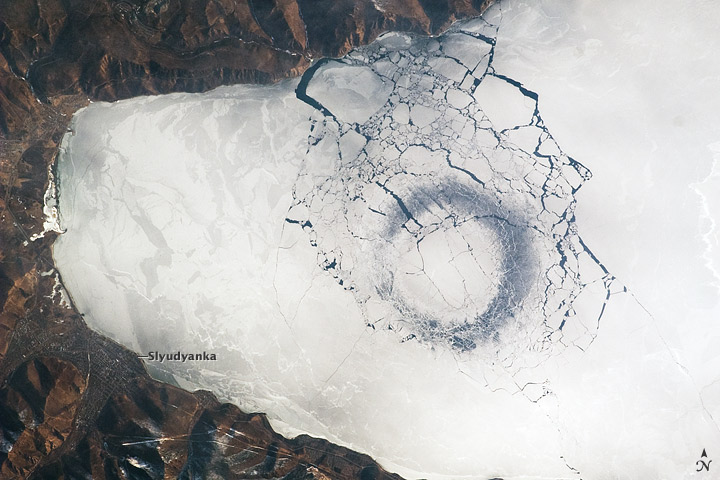

Thin Ice

Astronauts aboard the International Space Station snapped this shot of Lake Baikal in Siberia in April 2009. At the southern tip of the lake is a perfect, dark circle — the first sign of an impending ice breakup.

According to NASA's Earth Observatory, these spots of thin ice may be formed due to convection that brings warmer, deeper waters up toward the surface. Lake Baikal is the deepest lake in the world and the planet's largest single reservoir of fresh water. It reaches down 5,355 feet (1,632 m) at its deepest and holds 23,000 cubic kilometers of water. The lake is home to the nerpa, or Lake Baikal seal (Pusa sibirica), which is the only exclusively freshwater seal on the planet.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

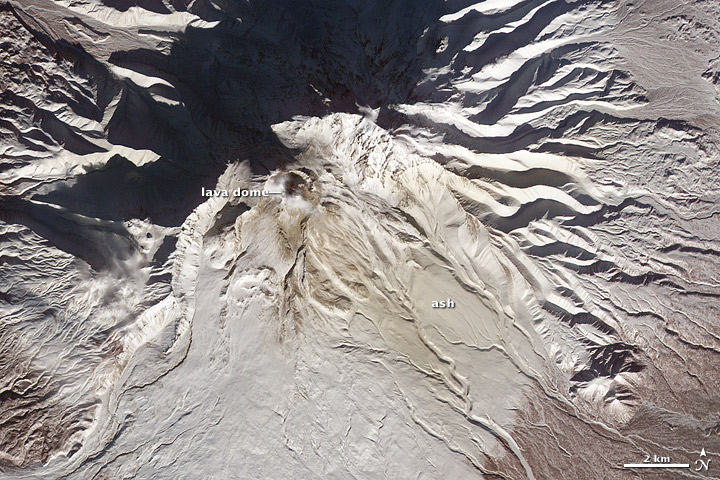

Growing Lava Dome

In February 2012, Russia's Shiveluch volcano was bulging. This satellite image shows the growing lava dome on top of the volcano, which sits on the Kamchatka Peninsula. According to the Smithsonian Institution's Global Volcanism Program, the mountain has been in an active period since at least the 1980s; as of April 2017, it was sending off periodic ash explosions and glowing menacingly. In this 2012 image, brown ash stains the southeastern slopes of Shiveluch and a cloud of gases partially obscures the peak.

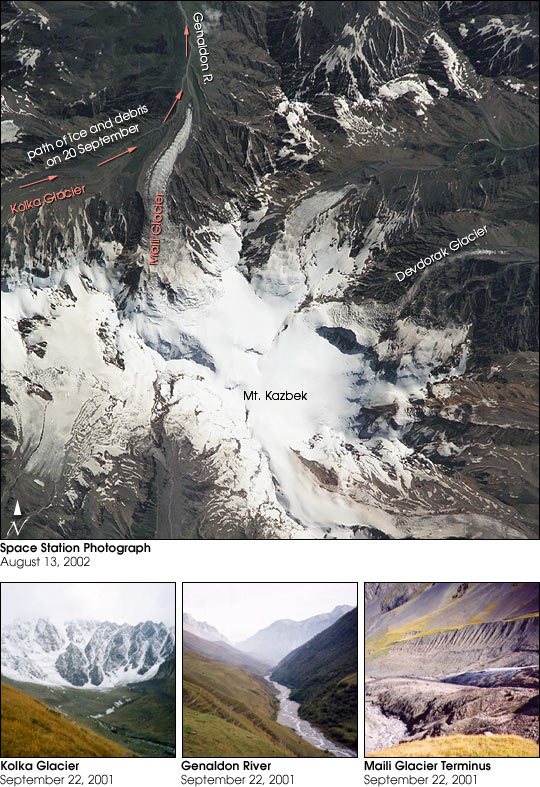

Glacial Danger

This 2002 photograph, taken by astronauts aboard the International Space Station, presages disaster. Only about a month after this photograph was taken, the Kolka Glacier (seen in the upper left) let loose an avalanche that buried small villages beneath the slope, killing 125 people. The avalanche started when a portion of a hanging glacier from the mountain face above fell onto the Kolka Glacier. Rocks and ice tumbled 8 miles (13 kilometers) before jamming at a gorge entrance called the Gates of Karmadon on the Genaldon River (also visible at the top of this image).

"The scale was so great that it really was hard to imagine how it could have happened," Sergey Chernomorets, an earth scientist at the University Center for Engineering Geodynamics and Monitoring in Moscow, told Earth Observatory of the resulting ice escarpment. “I have been studying there [the Caucasus] for many years, seen many debris flows and avalanches in this region, but nothing to compare to that."

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.