Shake Your Tail Feathers: Dinosaur Sported Modern-Looking Plume

A 145-million-year-old dinosaur about the size of a wild turkey sported a plume of tail feathers that were surprisingly modern-looking and aerodynamic in shape, a new study finds.

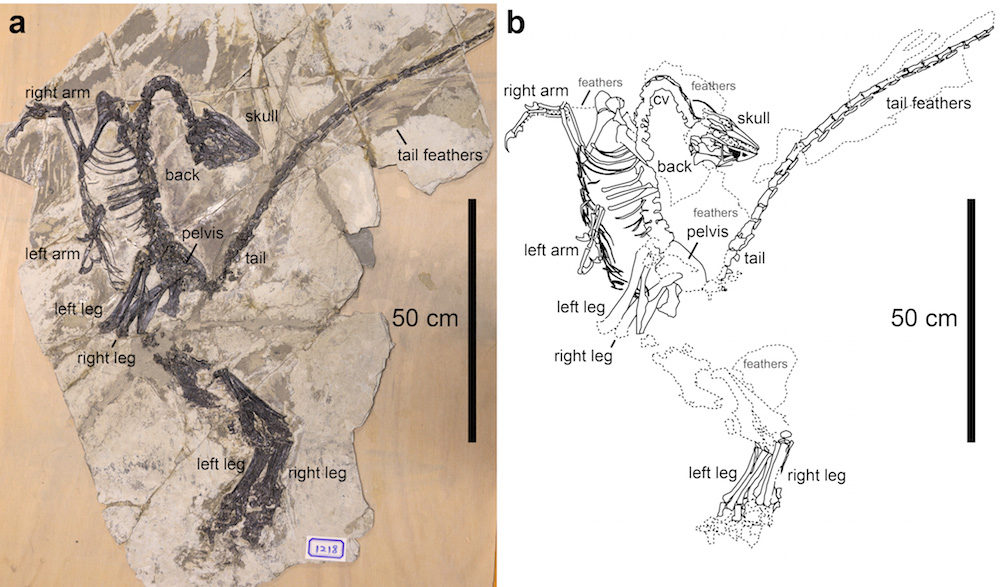

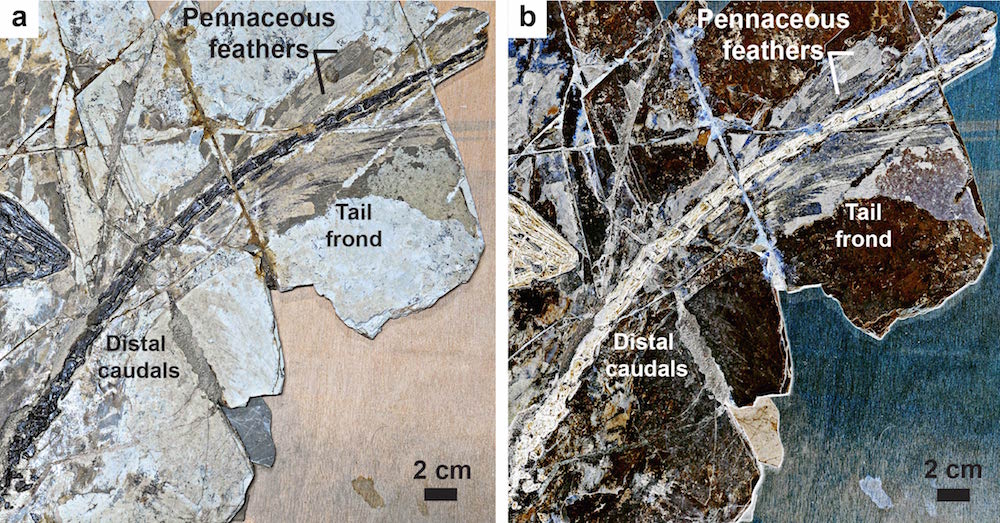

Though flight ready, the beast's tail feathers may or may not have been used for flying, said the researchers who found the exceptional specimen, a roughly 3.6-foot-long (1.1 meters) dinosaur, in 2015 in China's Liaoning Province, an area known for its incredibly well-preserved fossils of dinosaurs with feathers.

The scientists named the find Jianianhualong tengi, after Jianianhua, the Chinese company that supported the study, and "long," the Mandarin word for "dragon," the researchers said. The species name honors Fangfang Teng, the director of the Xinghai Paleontological Museum of Dalian in China, who helped the paleontologists access the specimen. [Images: These Downy Dinosaurs Sported Feathers]

J. tengi, which weighed just over 5 lbs. (2.4 kilograms), was a troodontid, a bird-like theropod. Though most theropods, such as Velociraptor and Tyrannosaurus rex, were carnivorous, J. tengi was likely an omnivore, based on its tooth anatomy and the diet of its closest relatives, said study co-lead researcher Michael Pittman, an assistant professor of vertebrate paleontology at the University of Hong Kong.

Asymmetrical feathers

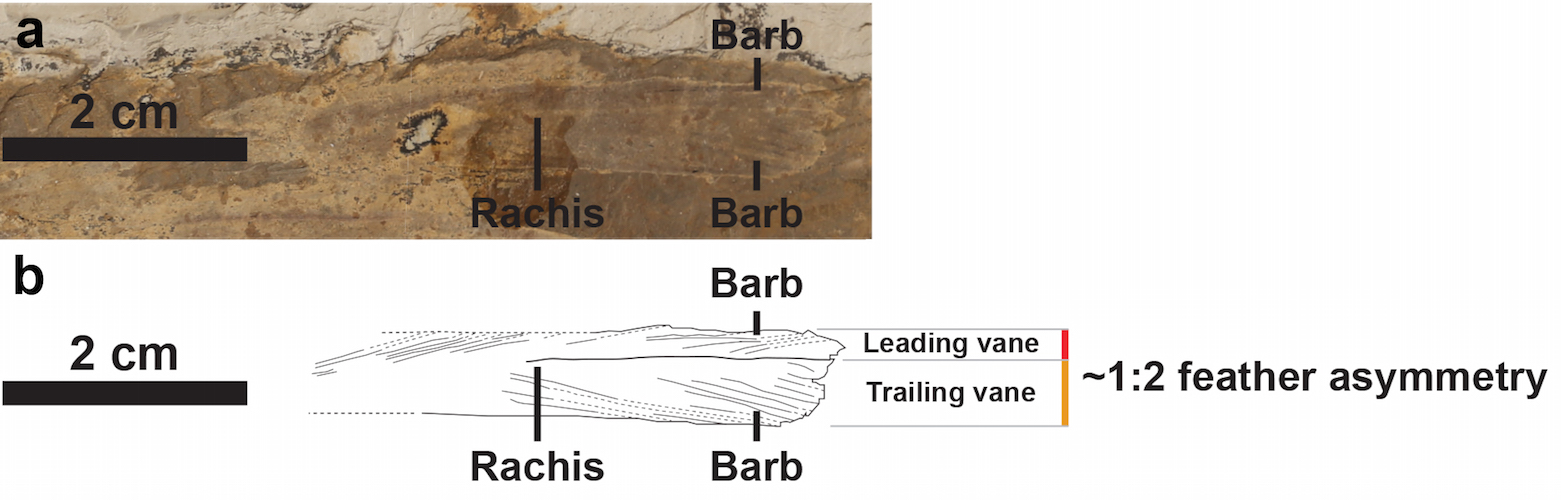

Unlike the symmetrical feathers seen on most dinosaurs from the Cretaceous period, J. tengi's feathers were asymmetrical, with the vanes on one side of the central shaft longer than those on the other side — a feature that is crucial for flight, the researchers said.

"Bird feathers need to be asymmetrical in order to form an airfoil," said Steve Brusatte, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh, who was not involved with the study. "It has to do with the physics of wing shape, the same way that airplane wings have to be designed a certain way."

However, asymmetrical feathers "are also found in species that do not fly," making it unclear whether the Cretaceous-age dinosaur could take flight, Pittman said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The asymmetrical feathers on J. tengi's tail are the first record of aerodynamically associated feathers in the bird-like troodontid dinosaurs, Pittman said. The Velociraptor relative Microraptor (a dromaeosaur) also had asymmetrical feathers, Pittman said.

"This reveals that the closest common ancestor of birds (shared with troodontids and the bird-like dromaeosaur dinosaurs, raptors), possessed asymmetrical feathers," Pittman told Live Science in an email.

The finding will likely help paleontologists decipher the timing of the evolution of asymmetrical feathers, both Pittman and Brusatte said.

"Strangely enough, the asymmetrical feathers are on the tail," Brusatte told Live Science in an email. "Does this mean that Jianianhualong was using its tail to fly? It's hard to be sure." [Photos: Velociraptor Cousin Had Short Arms and Feathery Plumage]

J. tengi's arm and leg feathers aren't preserved well enough to show their symmetry, "so we don't know what the feather condition of the entire animal would have been like," Brusatte said. "It is possible that Jianianhualong had asymmetrical tail feathers, but symmetrical (and thus non-flight-worthy) arm and leg feathers like most other nonbird dinosaurs. We just don't know."

Perhaps feather asymmetry evolved first for display purposes before the features were used for flight, Brusatte said. The investigation into the history of flight is a hot topic, as a growing number of researchers try to determine which dinosaurs could fly. For instance, research presented at the 2016 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting in Salt Lake City showed that several dinosaurs, such as Microraptor, and early birds, including Archaeopteryx, could likely fly for short distances, Live Science previously reported.

The new study was published online today (May 2) in the journal Nature Communications.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.