5 Questionable Health Screening Tests

Knowledge is power, unless that knowledge comes with so much baggage that it becomes crippling. Such is the trouble with many cancer and health screening tests.

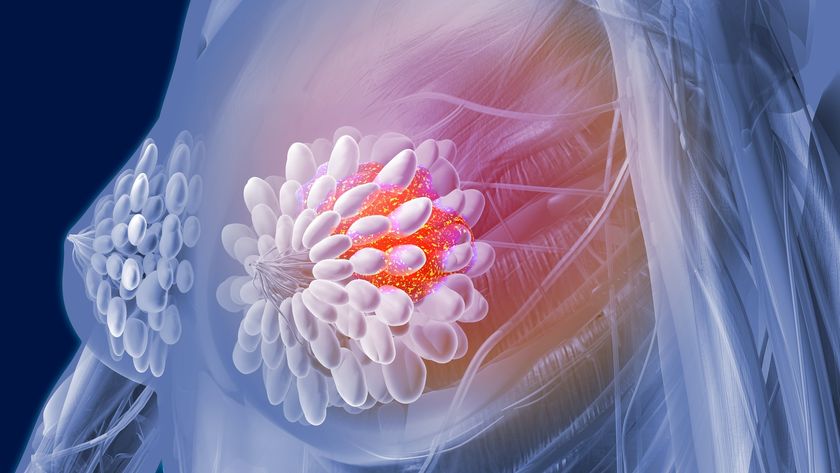

Last week the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force unleashed a maelstrom with its recommendations that women need mammograms less frequently, with regular breast-cancer screening starting at age 50, not 40, and only biennially, not yearly.

The Task Force said it was responding to data showing that routine mammograms starting at age 40, as long recommended, rarely save lives and more often result in a misdiagnosis — detection of a breast cancer that's either benign or growing too slowly to be of worry. This, in turn, leads to unnecessary anxiety and debilitating treatment.

Not everyone agreed with the new recommendations, published on November 17 online in the Annals of Internal Medicine. The American Cancer Society, for now, is sticking to its recommendation of yearly mammograms for women starting at age 40.

Yet nearly all health experts will agree that the benefits of most health screening techniques are either exaggerated by the health community or misunderstood by the public. A few discounted ones are below.

Five questionable tests

PSA testing: A PSA blood test looks for prostate-specific antigen, a protein produced by the prostate gland. High levels are associated with prostate cancer. The problem is that the association isn't always correct, and when it is, the prostate cancer isn't necessarily deadly. Nearly 20 percent of men will be diagnosed with prostate cancer, which sounds scary, but only about 3 percent of all men die from it. The PSA test usually leads to overdiagnosis — biopsies and treatment in which the side effects are impotence and incontinence.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

DEXA: Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA or DXA) in a technique developed in the 1980s that measures, among many things, bone mineral density. The scans can determine bone strength and signs of osteopenia, a possible precursor to osteoporosis. Limitations abound, though. Measurements vary from scan to scan of the same person, as well as from machine to machine. DEXA doesn't capture the collagen-to-mineral ratio, which is more predictive of bone strength than just mineral density. And higher bone mineral density doesn't necessarily mean stronger bones, for someone with more bone mass will have more minerals but could have weaker bones.

Full-body scans: If you got extra cash, usually more than $1,000, you may be tempted to get a full-body CT scan to find everything wrong with you. Avoid that temptation. For the most part, these are done so poorly by purely commercial enterprises that the results are useless. The scan will definitely find something abnormal that is likely of little concern. And it could very likely miss something that is a concern. For example, these scans aren't done with special contrast agents to look for specific types of tumors or organ damage. You're left only with a false sense of confidence. CT technology is excellent but only in the hands of an expert focused on a specific medical concern.

Home menopause test: The home menopause test is almost in the realm of hokum, despite its popularity with a generation of women who grew up with the home pregnancy test. The test measures levels of FSH, or follicle-stimulating hormone, in the urine. Not only doesn't the kit measure this well, FSH in the urine is a poor indicator of menopause status. Perhaps of little surprise is that FSH levels, like many female hormones, vary from day to day, particularly for pre-menopausal women. The home test kit may sound innocent enough, but some women might use this to assess whether they still need birth control.

Home Alzheimer's test: The home Alzheimer's test is a scratch-and-sniff test, useful according to the manufacturers because a loss of smell can be an early signs of Alzheimer's disease. There's a little truth here. Anosmia, a loss of smell, has been associated with Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. But that association seems rare; most anosmics don't have a degenerative brain disease. Your failure of the smell test is likely indicative of, well, a smelling problem. Yet while the home test verges on the naive, serious research continues on whether anosmia serves as some sort of canary in the coal mine for burgeoning neurological disorders.

Two good tests

Aside from self-examination for skin cancer, colon and cervical cancer screens are the only screens strongly recommended by most doctors.

Colonoscopies are very effective in finding and removing precancerous polyps. Colon cancer takes nearly a decade to develop, and starting a decadal colonoscopy routine at age 50 would significantly eliminate your risk for colon cancer. Similarly, Pap smears are highly effective identifying precancerous and malignant cervical cancer cells. Women should get a Pap smear at least every other year starting at age 20.

Health screenings aren't entirely useless. They are essential, in fact, for people at high risk of developing a disease, such as women with a clear family history of breast cancer. Screening is simply imperfect, and the public needs to understand the benefits and limitations of each one.

Christopher Wanjek is the author of the books "Bad Medicine" and "Food At Work." His column, Bad Medicine, appears each Tuesday on LiveScience.

Christopher Wanjek is a Live Science contributor and a health and science writer. He is the author of three science books: Spacefarers (2020), Food at Work (2005) and Bad Medicine (2003). His "Food at Work" book and project, concerning workers' health, safety and productivity, was commissioned by the U.N.'s International Labor Organization. For Live Science, Christopher covers public health, nutrition and biology, and he has written extensively for The Washington Post and Sky & Telescope among others, as well as for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he was a senior writer. Christopher holds a Master of Health degree from Harvard School of Public Health and a degree in journalism from Temple University.