Why Jimmy Kimmel's Newborn Son Needed Heart Surgery

Late-night host Jimmy Kimmel's son was born with a heart defect, and the newborn needed surgery within days of his birth.

Kimmel described his son's surgery in an emotional monologue on his show last night (May 1).

The baby, named Billy, was born with a condition called "tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary atresia," Kimmel told viewers. Billy had open-heart surgery on April 24 and went home six days later, on April 30. [Heart of the Matter: 7 Things to Know About Your Ticker]

"He's doing great. He's eating, he's sleeping, he peed on his mother today while she was changing his diaper. He's doing all the things that he's supposed to do," Kimmel said.

Billy will need another operation in three to six months, and then a noninvasive procedure when he's in his teens, Kimmel said.

But what is tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary atresia? And how is it treated?

The condition is a relatively common type of congenital heart defect, one that pediatric cardiologists and surgeons generally see many times each year, said Dr. Joseph Rossano, the executive director of the Cardiac Center at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Rossano was not involved in Kimmel's son's case.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The condition involves problems with the heart's structure that change the way that blood flows through the heart, causing the baby to have lower levels of oxygen in his or her blood than normal, Rossano told Live Science.

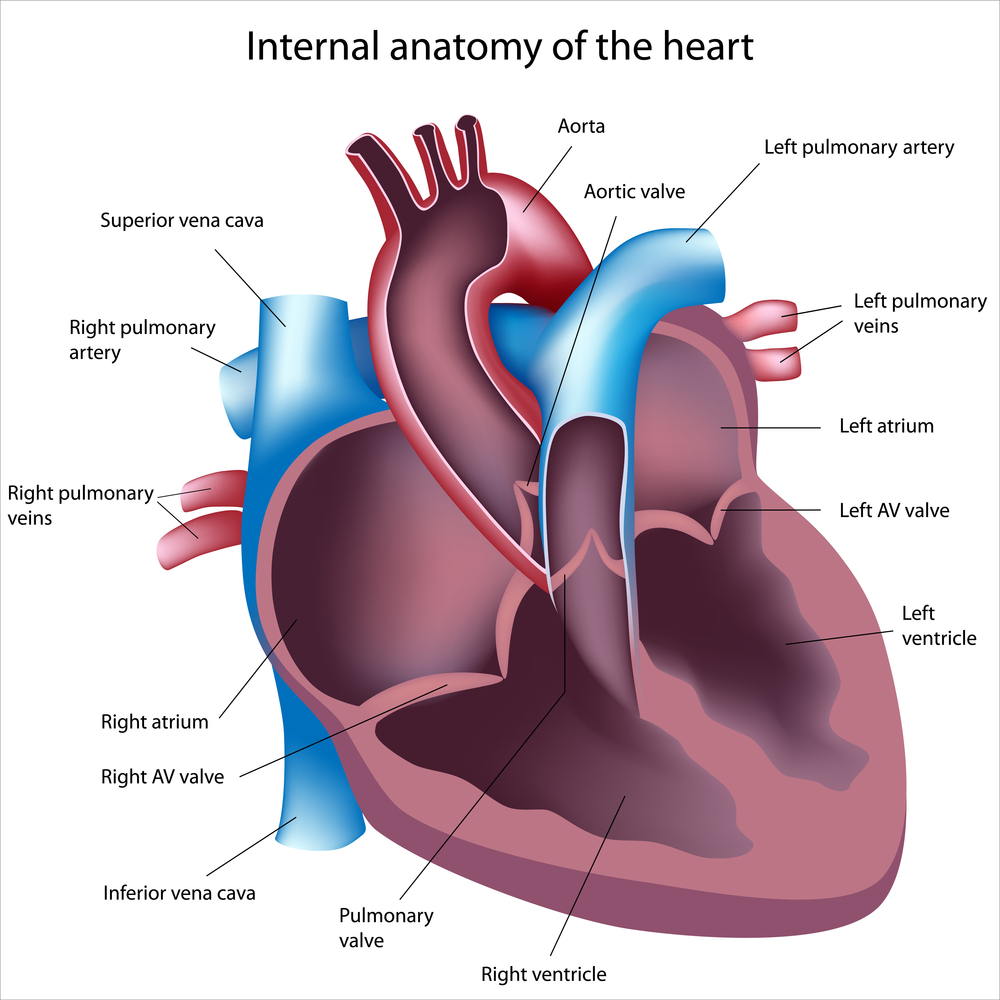

Normally, blood enters the right side of the heart and then is pumped through a blood vessel called the pulmonary artery to the lungs. In the lungs, the blood picks up oxygen, and then flows back into the left side of the heart. This oxygen-rich blood is then pumped out of the heart through the aorta, and into the rest of the body.

But when a person is born with tetralogy of Fallot with pulmonary atresia, the blood vessel that transports blood from the heart to the lungs is blocked, Rossano said. In addition, people with the condition have a defect in the wall of the heart that separates the two bottom chambers (the heart has four chambers), he said.

The result is that the blood can go from the right to the left side of the heart without first going to the lungs to pick up oxygen, Rossano said. Because the blood from the left side of the heart is pumped out into the rest of the body, this means that blood without oxygen is being pumped out of the heart, he said.

The severity of a baby's condition depends on the extent of the blockage in the blood vessel that leads to the lungs, Rossano said. In some cases, the vessel may be blocked just a little, so enough blood gets to the lungs and the baby's oxygen levels are normal.

But in severe cases, the blood vessel can be completely blocked, Rossano said. ("Atresia" is a medical term that refers to a passage in the body being closed off.) In these cases, babies must rely on another blood vessel, called the ductus arteriosus, to carry blood from the heart to the lungs, Rossano said. The ductus arteriosus is a blood vessel that's open when a baby is still in the uterus, but closes a day or so after the baby is born, Rossano said. A medication called prostaglandin can help keep the ductus arteriosus open until the baby can have surgery or a procedure to fix the defect.

Most children who are born with this condition undergo a "complete" repair, Rossano said. That means closing the defect between the right and left side of the heart and making sure that blood can flow normally from the right side of the heart to the lungs, he said. [The 7 Biggest Mysteries of the Human Body]

This surgery can take place shortly after the baby is born or after the child has grown a bit, Rossano said. The "vast majority" of children end up having the complete repair before age 1, he said.

Rossano noted that although children with this condition need follow-ups for the rest of their lives, "many of these children if not most are really thriving."

Kids with the condition can still lead a pretty normal childhood, he said. It's a "serious heart defect," Rossano added, "but it's treatable."

Originally published on Live Science.