Hindenburg Crash: The End of Airship Travel

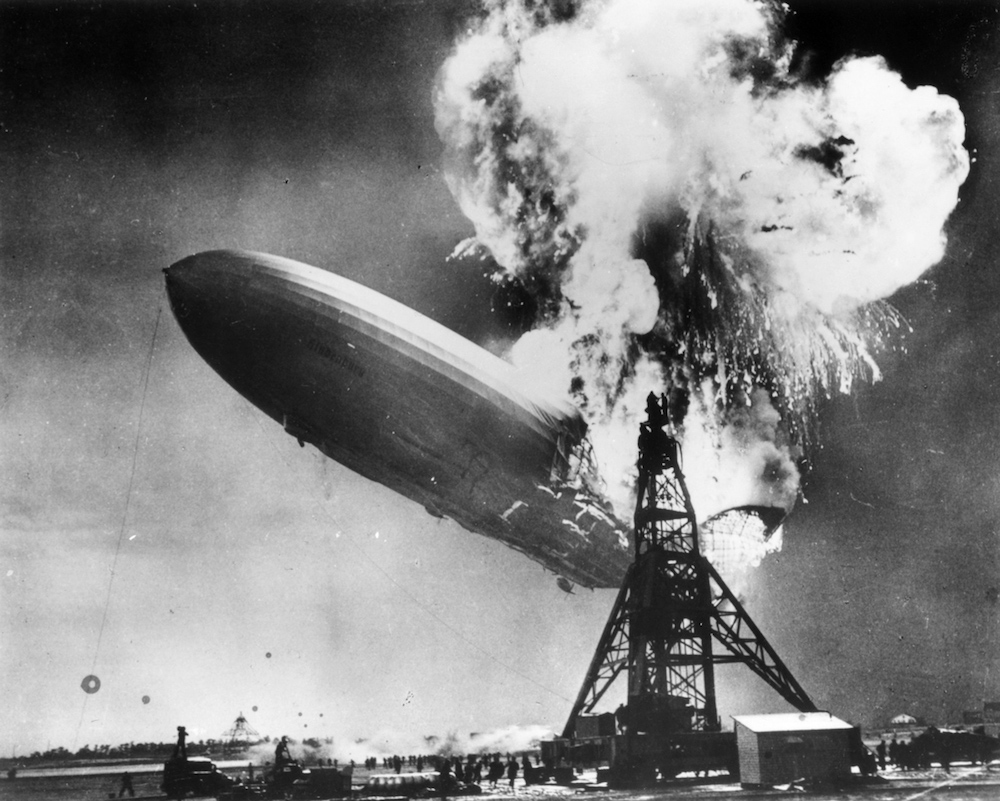

On May 6, 1937, the German zeppelin Hindenburg exploded, filling the sky above Lakehurst, New Jersey, with smoke and fire. The massive airship's tail fell to the ground while its nose, hundreds of feet long, rose into the air like a breaching whale. It turned to ashes in less than a minute. Some passengers and crewmembers jumped dozens of feet to safety while others burned. Of 97 people aboard, 62 survived.

At the time, the Hindenburg was supposed to be ushering in a new age of airship travel. But the crash instead brought the age to an abrupt end, making way for the age of passenger airplanes. The crash was the first massive technological disaster caught on film, and the scene became embedded in the public's consciousness. A horrified radio reporter's exclamation — "Oh, the humanity!" — has since become somewhat of a catchphrase. Speculation about the cause of the crash has been the subject of numerous books and movies. "It was like the Titanic in that sense," said Dan Grossman, an aviation historian at Airships.net and author of "Zeppelin Hindenburg: An Illustrated History of LZ-129."

A luxurious leviathan in the sky

Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, a German military officer, developed the first rigid-framed airships in the late 1800s. He had observed hot-air balloons in the United States during the Civil War, according to Airships.net. He built his first airship, LZ-1, in 1899. Over time, his name became synonymous with all rigid airships.

The Hindenburg — officially designated LZ-129 Hindenburg — was the biggest commercial airship ever built, and at the time, the most technologically advanced. It was 245 meters (803.8 feet) in length and 41.2 m (135.1 feet) in diameter, according to Airships.net. It was more than three times larger than a Boeing 747 and four times the size of the Goodyear Blimp. It could reach cruising speeds of 122 km/h (76 mph) and a maximum speed of 135 km/h (84 mph).

The Hindenburg featured 72 passenger beds in heated cabins, a silk-wallpapered dining room, a lounge, a writing room, a bar, a smoking room, and promenades with windows that could be opened in-flight. The furniture was designed using light-weight aluminum. Special precautions were taken to ensure that the smoking room was safe, including a double-door airlock to keep hydrogen from entering, according to the American Enterprise Institute.

The Hindenburg was named for former German Weimar Republic president Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934). It took its first flight in March 1936, and flew 63 times, primarily from Germany to North and South America, said Grossman.

Development and technology

Blimps, zeppelins and hot-air balloons are all types of lighter-than-air airships. They are kept aloft through a lifting gas, such as helium, hydrogen or hot air. Zeppelins, including the Hindenburg, have rigid frames constructed of rings and longitudinal girders. Gas cells allow them to maintain their shape without deflating, unlike hot air balloons and blimps, according to Space.com.

The frame was built of duralumin, an aluminum alloy. The Hindenburg was wider than other airships, which made it more stable. Four engines powered the Hindenburg.

Sixteen gas cells made from gelatinized cotton kept the Hindenburg aloft. These cells were designed to be filled with helium, which was known to be safer than hydrogen because it is non-flammable. However, the Germans could not obtain helium. It was very expensive, required more operators, and reduced the payload. Most importantly, only the United States and Soviet Union had helium at the time, said Grossman.

"No one was doing business with the Soviets and because helium was difficult to extract, the U.S. had a law that prohibited exporting helium," he said. "One myth is that the Hindenburg didn't have helium because the U.S. wouldn't sell it to the Nazis. That is not true; the prohibition was passed six years before the Nazis took power. By 1936, the U.S. was making more helium and it is possible they would have sold it to the Germans, but they never asked for it."

Nazi pride, the ongoing economic depression in Germany and the difficulties of making a profit with a helium-lifted airship all prevented the Germans from attempting to use helium for the Hindenburg, said Grossman.

The crash

On its final, fateful voyage, the Hindenburg took off from Frankfurt, Germany, on May 3, 1937. The trip was smooth, though headwinds slowed the crossing and delayed the estimated landing time by 12 hours. Bad weather awaited in New Jersey, where thunderstorms had raged all day. Captain Max Pruss and other senior officers aboard the Hindenburg requested delaying the landing further and flew the ship around the beaches until weather conditions improved somewhat, according to Airships.net.

The Hindenburg approached Lakehurst just after 7 p.m. on May 6. Concerned that weather conditions would deteriorate and faced with changing wind patterns, the officers decided to execute a sharp S-turn to land in a better direction for the current gusts, according to Airships.net. After the turn was made, landing lines were dropped. Handlers on the ground used these ropes to help guide the landing. The Hindenburg was about 180 feet in the air.

A few minutes after the landing lines were lowered, members of the ground crew saw what they described as "wave-like fluttering" beneath the ship's fabric covering near the end of the ship, possibly caused by hydrogen that had escaped from its cell, according to The Royal Society of Chemistry.

At 7:25 p.m., flames appeared on the Hindenburg's tail. Within seconds, fire covered the entire tail. The tail sank to the ground and the nose jutted up into the sky for several seconds before crashing down, engulfed in flames, according to Don Adams, a coordinator and historian at the Navy Lakehurst Historical Society, which maintains the Hindenburg crash site. The fabric covering was gone, leaving the duralumin skeleton standing for a moment before it buckled and collapsed.

"It took only 34 seconds to burn," said Adams. "People are always shocked by that. Just 34 seconds."

Because of the speed of destruction, survival mostly depended on where passengers and crew were at the time the fire started, Adams continued. Most people on the periphery of the ship were able to jump to safety. Most passengers in their cabins died. More crewmembers than passengers perished because they were scattered throughout the ship, while the majority of passengers had gathered at the windows to watch the landing.

The crash was filmed by four newsreel companies, though none caught the first moments of fire. "They always had reporters and film crews when it landed because celebrities flew on it," said Adams. "It was the thing to do at the time. Thousands of people would come to watch the landings."

The most famous media from the Hindenburg crash is Herbert Morrison's eyewitness radio account, which was broadcast by WLS Chicago the next day. In it, he describes the scene in vivid detail and exclaims his famous line: "Oh, the humanity!"

What caused the crash?

There are several theories about the reason for the crash, which range from crackpot to respectable, according to Grossman. When it comes to the basics of what happened, "there is zero controversy among all respectable scholars in the field," he said. It is established that there was a leak in the fuel cells, hydrogen escaped and mingled with oxygen, creating a highly flammable mixture, which then ignited and caused a massive fire.

There is no evidence to support theories that a bomb or arrow hit the Hindenburg in an act of sabotage or that a chemical or material other than hydrogen caused the fire. "The most well-known crackpot theory is that the fabric was extremely flammable," said Grossman, who wrote an essay about Hindenburg myths. "It was not. There is no evidence that it was. Airships in general and the Hindenburg in particular had been hit by lightning. Hydrogen airships had been hit by lightning frequently enough to burn holes in the covering but they never caused a fire because the hydrogen wasn't leaking."

What remains uncertain is why the hydrogen was leaking and exactly how it was ignited. "There are a lot of speculations on why the leak happened," said Adams. A common theory is that the sharp S-turn caused a wire to snap and cut into a gas cell, but that has been "pretty much disproved," said Grossman. "Given that all the evidence burned up, we'll probably never know why it was leaking."

Experts do have a good idea of what caused the ignition. There are two primary theories: electrostatic discharge and St. Elmo's Fire. Both Adams and Grossman subscribe to the electrostatic discharge theory of ignition "to the extent that you can say anything with certainty when reconstructing an accident," said Grossman. In both theories, the high electric charge on the day, caused by the lightning storms, plays an important part.

"You could still see the lightning [when the ship was landing]," said Grossman. "There was so much electricity in the air that nearby rubber factories were closed (rubber dust is highly explosive)." Flying through the air, the ship had a positive charge. When the landing lines touched the ground, they received a negative charge. "It was like walking across the rug and touching the doorknob," said Adams. "You are the positive charge and the knob is negative. Anytime you have two differences in electrical potential, a spark is likely to jump."

"The nature of the electrostatic discharge theory that I find most convincing is that it's consistent with as much of the physical evidence as we have," said Grossman. "There was a difference in the electric potential of the metal framework of the ship, which was grounded by the landing lines, and the fabric covering of the ship which, was electrically isolated from the framework. There was no way the charge in the fabric could discharge or equalize because it wasn't connected to anything that was conductive. It was connected to nonconductive rami cords and wooden dowels. So you had a huge electrical charge on the fabric and a very different electrical charge on the framework because the ship was 60 to 80 meters in the air but the framework had the electrical charge of the ground."

Grossman noted that St. Elmo's Fire, or brush discharge, which is caused by a difference in electrical charges between an object and the air, could have also caused the spark. "There was so much electricity in the air, it could have easily happened. But neither St. Elmo's Fire or electrostatic discharge would have been dangerous if there hadn't been a hydrogen leak."

Nazi connection

"Never forget the role Nazi of pride," said Grossman. "Nazis lay over this story."

The Hindenburg was already under construction when the Nazis came into power in Germany in 1933. The Third Reich saw the zeppelin as a symbol of German strength, according to History.com. The Hindenburg was partly owned by the government and partly owned by the Zeppelin Company, its creators. Giant swastikas were painted on its tail fins.

The German minister of propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, ordered the Hindenburg to embark on a propaganda mission early on, before the ship's endurance tests had even been completed. For four days, it flew around Germany, blasting patriotic songs and dropping pro-Hitler leaflets, said Grossman. The weather was bad during the flight, and commander Ernst Lehmann ended up damaging the tail.

Some theorize that the crash was an act of anti-Nazi sabotage. While Grossman noted that many people would have been happy to see the Nazi ship go up in the flames, there is no physical or witness evidence to support that possibility. "But," he said, "there is so much evidence that points to the static-electro discharge theory."

Nazis played a role in the Hindenburg crash in another way, however. Lehmann, the senior officer aboard the Hindenburg, and Pruss, captain of the ship, were both influenced by the Nazi Party. Pruss was a party member and while Lehmann was not, he "had a demonstrated history of bowing to Nazi pressure," said Grossman. "He damaged the Hindenburg on the propaganda flight because he did something a Nazi officer told him to do that he knew wasn't a good idea. After that, three of the four untested engines failed on the first flight back from Rio."

During the last flight, Hindenburg officers were under pressure from the Nazi party to stay on a strict time schedule. Adams explained that while the Hindenburg was only half full on its flight from Frankfurt to Lakehurst, it was fully booked with celebrities, dignitaries and other notables for the return flight. They needed to get to Europe to attend the coronation of Britain's King George VI. "They were already late coming into Lakehurst so they wanted to try and make up that time and do a fast turn around and get out of here," he said. "He (Lehmann) was almost like a fanatic on keeping his schedule."

This fanaticism came from a place of fear. Not arriving in time for the coronation would have reflected poorly on the Germans, and the Nazi party was very sensitive to public opinion, explained Grossman. "Hindenburg officers knew the weather wasn't right but were asking themselves, 'Who are we more afraid of, the weather or the Gestapo?' The weather may or may not kill you but you can't say that about the Gestapo."

Lehmann and Pruss were criticized, even after their deaths, for bowing to Nazi pressure and attempting to land the Hindenburg in bad conditions. Thy should have waited for the electricity in the air to dissipate before landing, according to Grossman.

Aftermath

The Hindenburg crash ended the airship era. "No one wanted to fly with hydrogen ships anymore; they were afraid of it," said Adams. "Not only that, as Hitler gained more power, people really didn't want to fly on a Nazi airship."

American and German companies had plans to build more airships and saw the Hindenburg as a test case for their investment, said Grossman. After the crash, those plans were canceled.

But technological advancements also contributed to the demise of airship popularity. "The Hindenburg would have been an amazing technical achievement in 1928. But by 1936, it was out of date because of fixed wing heavier-than-air airplanes," said Grossman. "When it was launched, there were already aircraft that could fly faster, carry as much, fly cheaper, with fewer crew, that were better in every way.

"Even if the Hindenburg hadn't burned, it would have been made obsolete by aircraft."

Additional resources

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jessie Szalay is a contributing writer to FSR Magazine. Prior to writing for Live Science, she was an editor at Living Social. She holds an MFA in nonfiction writing from George Mason University and a bachelor's degree in sociology from Kenyon College.