Pinky-Sized Marine Animal Breaks Record for Ocean Filtration

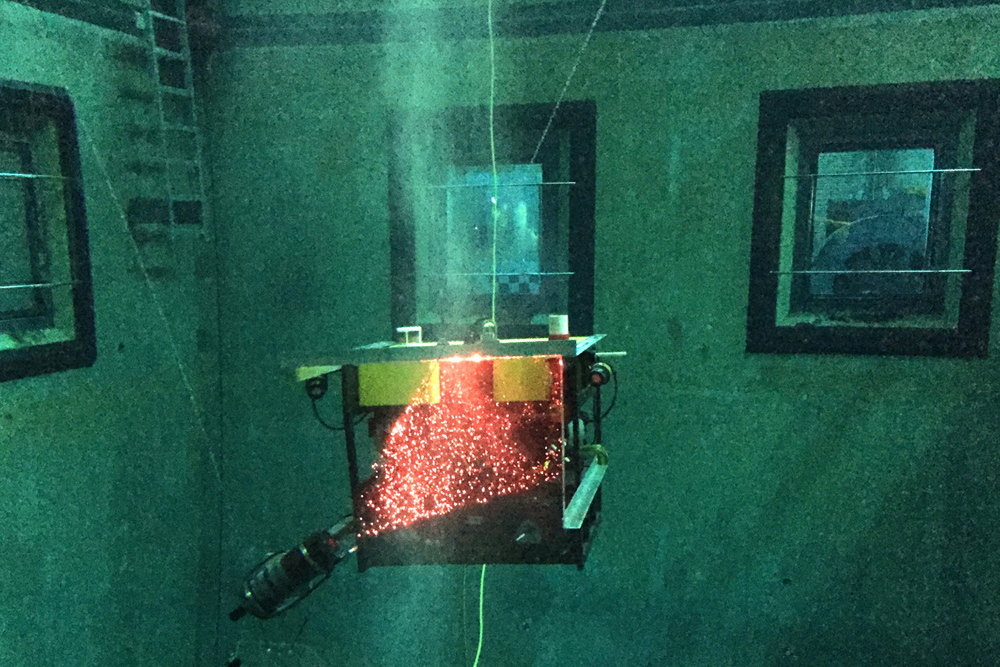

Giant larvaceans, marine animals the size of a human pinky, are so fragile that nets destroy them. Scientists have therefore desired to study them in the wild, but only recently achieved the feat using a remotely operated vehicle that launched a high-tech laser and optics gadget, DeepPIV, which looks like something out of a James Bond film. Kakani Katija, who led the effort from aboard the surface vessel Rachel Carson in Monterey Bay, described what happened next.

"When we turned off the white lights and turned on the laser, there was a collective gasp in the room — we couldn't believe what we were seeing," said Katija, who is the principal engineer at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute.

"We could see the larvacean pumping its tail," she continued. "We could see the interior chambers of the filters. We could see the motion of fluid in and through the house (the animal's filtration system)."

It was then that her colleague, senior scientist Bruce Robison, shouted, "Wow! We're pulling back the veil of ignorance."

RELATED: These Overlooked Organisms Are the Key to Life as We Know It

Doing so revealed that a giant larvacean known as blue-tailed Bathochordaeus filters particles out of water faster than any other marine creature. It beats the prior record holder, plankton called salps. The findings are reported in the journal Science Advances.

Giant larvaceans, a type of zooplankton, are the key to the so-called biological pump. This is a process whereby organisms in the ocean transport carbon from the atmosphere into the deep sea, where some of that carbon is sequestered.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Capturing and sequestering carbon help to mitigate global climate change, so we and every other species on the planet benefit from the ocean filtration talents of these tiny creatures every day of our lives.

"We have estimated that as much as a quarter of the organic carbon transported to the deep bottom of Monterey Bay comes from discarded giant larvacean houses," Robison said, adding that giant larvaceans are also located in oceans across the world.

He and Katija explained that giant larvaceans first make the rudimentary filtration "house" by excreting mucus from a series of cells located on its head.

"At some point in the build process, the larvacean starts moving its tail in a specific fashion, where we suspect the animal is forcing fluid through the house rudiment, and effectively blows up the rudiment like a balloon," Katija said.

The house is then ready for action, filtering phytoplankton and other organic particles. These materials stick in the mucus house for digestion. When the filtration system fills up with waste matter, the entire nutrient-rich house is discarded and sinks to the sea floor. There, it provides a source of food for deep-sea animals. Giant larvaceans at that point may swim to another location, prior to building another house, in order to start the process all over again.

RELATED: 'Mythical' Sea Blob Finally Spotted a Century After Its Discovery

The animals have such an effective filtration system that researchers have even considered adding them to the ocean to do more good work. That idea was shut down quickly, however, due to concerns over unintended consequences, such as disruption of the marine ecosystem.

Robison said scientists of the past learned hard lessons about unintended consequences. He then listed some of the colossal failures: bringing mongooses to Hawaii to control rats in sugar cane fields (mongooses became an invasive species there); dumping radioactive waste in the ocean (causing pollution and hurting marine life); and bringing kudzu plants from Japan into the states to feed livestock (kudzu became an invasive species).

"The list goes on and on," he added. "Upsetting the balance of nature can be a tricky business, especially when dealing with an ecosystem as poorly known as the deep sea."

The researchers, however, hope to further study larvaceans. They also plan to use DeepPIV to obtain more accurate measurements of carbon removal by other deep-water organisms.

"Who knows what else is out there?" Robison asked. "The deep ocean is the least explored habitat on Earth, and we are only beginning to learn who is out there and how it all works."

Originally published on Seeker.