Embryo of colossal dinosaur was preserved for 90 million years

About 90 million years ago, a gigantic bird-like dinosaur with a toothless beak and a crest atop its head laid a clutch of enormous eggs. At least one of these eggs never hatched, but rather became the first and only one of its species on record to fossilize, according to a new study.

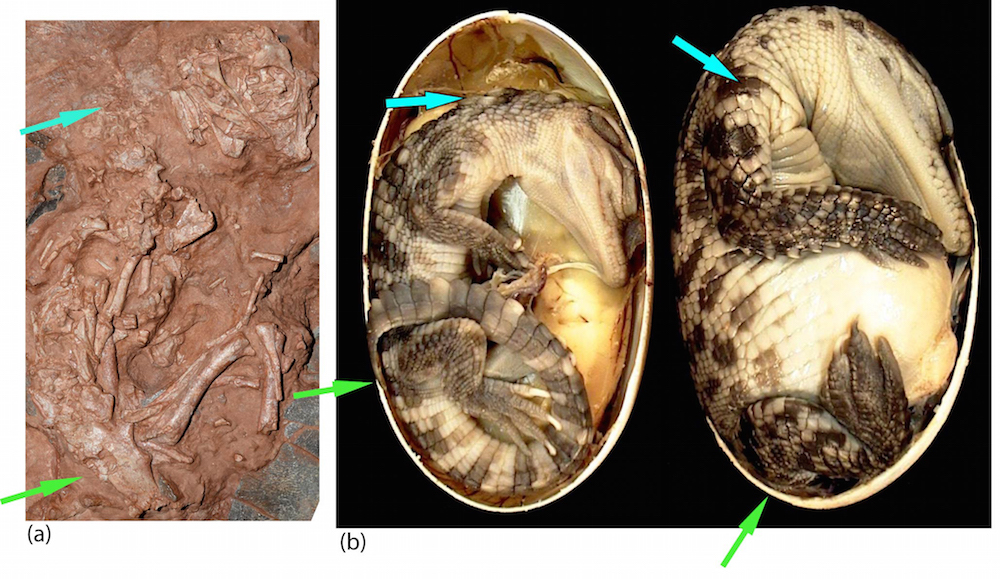

The discovery of the 15-inch-long (38 centimeters) embryo is remarkable, said study co-researcher Darla Zelenitsky, an assistant professor of paleontology at the University of Calgary in Alberta, Canada.

"This is the first embryo known for a giant oviraptorosaur, dinosaurs that are exceedingly rare," Zelenitsky told Live Science in an email. [See Images of the Newly Named Giant Oviraptorosaur Embryo]

Moreover, it's only the second species of giant oviraptorosaur on record, Zelenitsky said. The other known giant oviraptorosaur is dubbed Gigantoraptor, a beast that stood as tall as 16 feet (5 meters).

Baby Louie's journey

After the fossilized embryo's discovery, it took 25 years for the previously unidentified Cretaceous-age specimen to receive an official scientific name.

A Chinese farmer in Henan Province found the oviraptorosaur embryo in 1992, and a year later it was exported to the United States by The Stone Co., a Colorado firm that sells fossils and rocks. Word spread when the company uncovered the eggs and embryo, and National Geographic featured it on a magazine cover in 1996.

The National Geographic photographer, Louis Psihoyos, captured so much detail in his shots that people began calling the dinosaur "Baby Louie," even after it went on display at the Children's Museum of Indianapolis.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, because of Baby Louie's significance (an embryo representing a new species of rare dinosaur), researchers decided to wait until it was repatriated to China in 2013 to study it, Zelenitsky said.

After the examination at the Henan Geological Museum, a group of researchers from China, Canada and Slovakia gave Baby Louie the formal scientific name of Beibeilong sinensis, which means "baby dragon from China," in a combination of Mandarin and Latin. [Image Gallery: Dinosaur Day Care]

Towering giant

Giant oviraptorosaurs are two-legged dinosaurs that looked like modern-day cassowaries — large, flightless birds that live in Australia. But an adult B. sinensis would have towered over the 6.5-foot-tall (2 m) cassowary, and even a typical oviraptorosaur, such as Oviraptor, Zelenitsky said.

B. sinensis measured up to 26 feet long from its snout to the end of its tail, and it weighed up to 6,600 lbs. (3,000 kilograms) when fully grown at age 11. That means B. sinensis underwent a substantial growth spurt, as it likely weighed just under 9 lbs. (4 kg) after it hatched, Zelenitsky said.

While the incredibly well-preserved specimen and eggs — huge, elongated fossils that measured up to 17 inches (45 centimeters) long and weighed about 11 lbs. (5 kg) — have helped the researchers learn about B. sinensis, they don't contain many clues about the dinosaur's parenting style. It's unclear whether the parents protected the nest and cared for the young because no adult material was found with the nest, Zelenitsky said.

Still, the finding reveals that these enormous eggs — the largest known dinosaur eggs on record, which even have a formal name: Macroelongatoolithus, meaning "large elongate stone egg," — came from giant oviraptorosaurs, she said.

"Because Macroelongatoolithus eggs are common in the fossil record, the established link between Macroelongatoolithus and giant oviraptorosaurs enabled us to infer that these animals were much more abundant, common [and] widespread than indicated by the scarcity of their bones," Zelenitsky said.

The study was published online today (May 9) in the journal Nature Communications.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.