Paper-thin Batteries Made from Algae

Imagine wrapping paper that could be a gift in and of itself because it lights up with words like "Happy Birthday." That is one potential application of a new biodegradable battery made of cellulose, the stuff of paper.

Scientists worldwide are striving to develop thin, flexible, lightweight, inexpensive, environmentally friendly batteries made entirely from nonmetal parts. Among the most promising materials for these batteries are conducting polymers.

However, until now these have impractical for use in batteries — for instance, their ability to hold a charge often degrades over use.

Easy to make

The key to this new battery turned out to be an often bothersome green algae known as Cladophora. Rotting heaps of this hairlike freshwater plant throughout the world can lead to unsightly, foul-smelling beaches.

This algae makes an unusual kind of cellulose typified by a very large surface area, 100 times that of the cellulose found in paper. This allowed researchers to dramatically increase the amount of conducting polymer available for use in the new device, enabling it to better recharge, hold and discharge electricity.

"We have long hoped to find some sort of constructive use for the material from algae blooms and have now been shown this to be possible," said researcher Maria Strømme, a nanotechnologist at Uppsala University in Sweden. "This creates new possibilities for large-scale production of environmentally friendly, cost-effective, lightweight energy storage systems."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

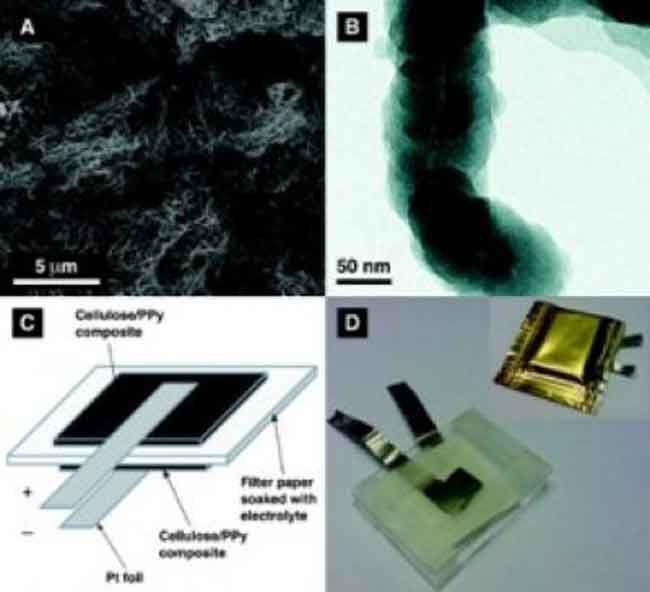

The new batteries consisted of extremely thin layers of conducting polymer just 40 to 50 nanometers or billionths of a meter wide coating algae cellulose fibers only 20 to 30 nanometers wide that were collected into paper sheets.

"They're very easy to make," Strømme said.

Quick to charge

They could hold 50 to 200 percent more charge than similar conducting polymer batteries, and once better optimized, they might even be competitive with commercial lithium batteries, the researchers noted. They also recharged much faster than conventional rechargeable batteries — while a regular battery takes at least an hour to recharge, the new batteries could recharge in anywhere from eight minutes to just 11 seconds.

The new battery also showed a dramatic boost in the ability to hold a charge over use. While a comparable polymer battery showed a 50 percent drop in the amount of charge it could hold after 60 cycles of discharging and recharging, the new battery showed just a 6 percent loss through 100 charging cycles.

"When you have thick polymer layers, it's hard to get all the material to recharge properly, and it turns into an insulator, so you lose capacity," said researcher Gustav Nyström, an electrochemist at Uppsala University. "When you have thin layers, you can get it fully discharged and recharged."

Flexible electronics

The researchers suggest their batteries appear well-suited for applications involving flexible electronics, such as clothing and packaging.

"We're not focused on replacing lithium ion batteries — we want to find new applications where batteries are not used today," Strømme told LiveScience. "What if you could put batteries inside wallpaper to charge sensors in your home? If you could put this into clothes, can you couple that with detectors to analyze sweat from your body to tell if there's anything wrong?"

Future directions of research include seeing how much charge these batteries lose over time, a problem with polymer batteries and all batteries in general. They also want to see how much they can scale up these batteries, "see if we can make them much, much larger," Strømme said.

The scientists detailed their last month in the journal Nano Letters.

- 10 Technologies That Will Transform Your Life

- 10 Profound Innovations Ahead

- All About Electricity