Incredible! Most Well-Preserved Armored Dinosaur Was a 'Spiky Tank'

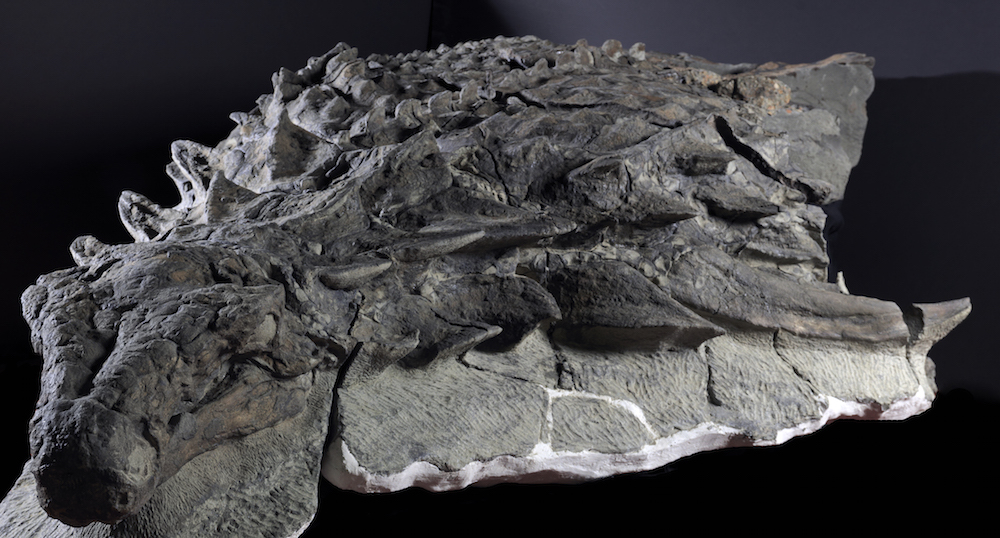

A spiky, tank-like dinosaur discovered in a Canadian mine is so well-preserved, it looks as if the fossilized creature were frozen in time for 110 million years.

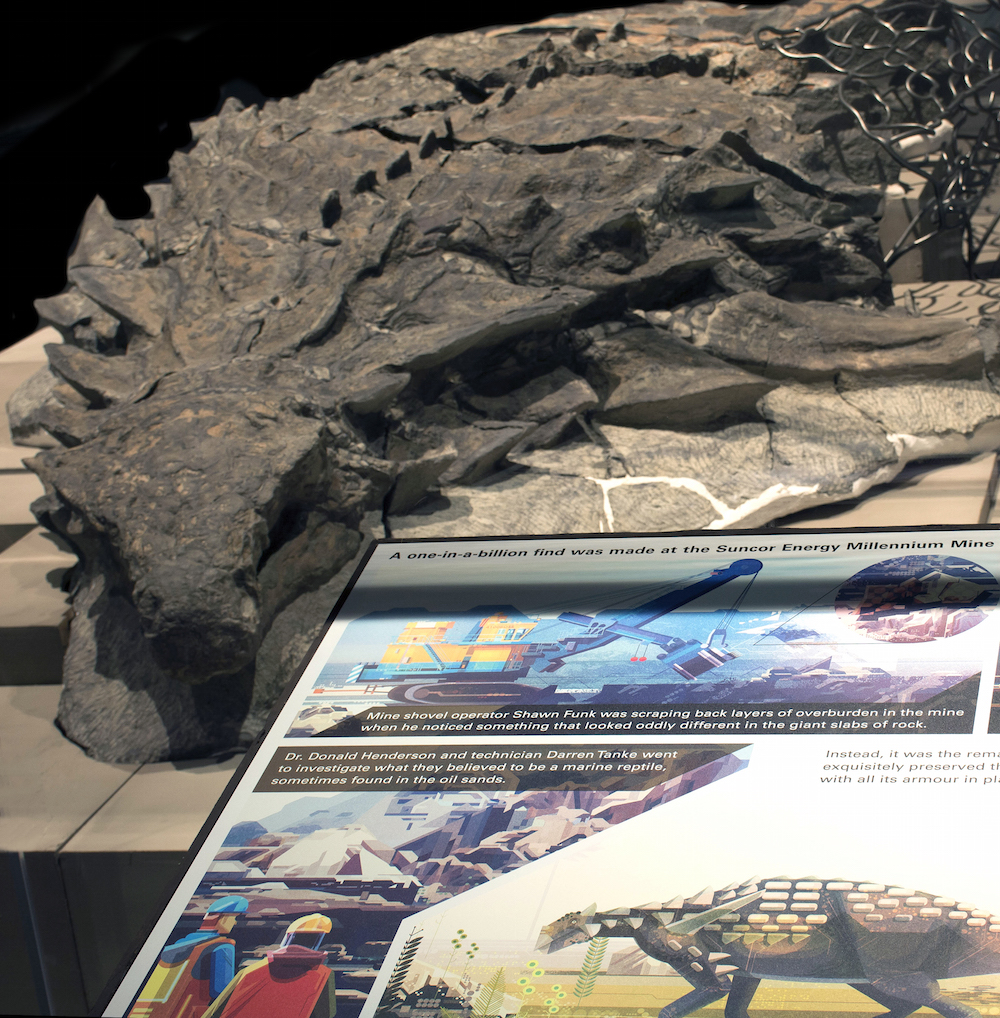

Miners discovered the 18-foot-long (5.5 meters) beast — a nodosaur, a cousin of ankylosaurs, which also had body armor but didn't sport club tails — in 2011 during routine work at the Suncor Millennium Mine in Alberta.

Shawn Funk, a heavy-equipment operator, noticed the fossil because the texture and color looked different than the surrounding rock, according to National Geographic, which broke the story on Friday (May 12). Soon after, the Suncor Energy company contacted the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology in Alberta, where the specimen has remained for the past six years, painstakingly being chiseled out, one inch at a time. [Photos: See the Armored Dinosaur Named for Zuul from 'Ghostbusters']

"It was a very slow reveal, but it was a very exciting one nonetheless," said Caleb Brown, a postdoctoral fellow at the museum, and a co-author of a study describing the new species, which he expects to be published in a peer-reviewed journal this summer.

Mysterious death

When the dinosaur died, Alberta was as warm as South Carolina is today, and sat on the coast of a shallow inland seaway that stretched from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Ocean. It's unclear if the dinosaur drowned in the seaway or died on land and then got swept out to sea, Brown said. Either way, the carcass would have undergone a phenomenon called "bloat and float" as the body decomposed and filled with gases.

After severe bloating, the carcass would have exploded and sunk to the bottom of the seaway. "It must have been a very quiet, a very muddy, fine-grained and low-oxygenated environment where it settled, because there is no scavenging on the animal," Brown said.

The nodosaur didn't land with a timid thump, either.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It must have fallen pretty rapidly, because we actually have a little impact crater from where it hit the bottom," Brown said. "It hit the bottom pretty hard."

Because the specimen was covered in marine sediment, museum researchers didn't know the specimen was a dinosaur. At first, they thought that the fossils belonged to a prehistoric marine creature, such as an ichthyosaur or a plesiosaur, because "we were getting marine reptiles from another mine about 20 kilometers [12 miles] away," said Donald Henderson, the curator of dinosaurs at the museum and co-author of the forthcoming study.

But after getting a good look at part of the specimen, museum technician Darren Tanke made the right call: The beast was a dinosaur, no doubt about it, Henderson said.

The excavation

In all, Henderson spent 17 days at the Millennium Mine in 2011, taking safety classes with Tanke so they could go into the mine to help excavate the specimen. The dinosaur was encased in a block of extremely hard rock known as a concretion, but the fossil inside was as soft as talcum powder, Henderson said.

The crew learned that the hard way, when they tried to remove the entire 35,000-lb. (15,800 kilograms) concretion at once. The insides were so soft, the block broke in two as they tried to remove it from the mine, Henderson said. After that, the paleontologists opted to remove the fossils in several thousand-pound chunks, which were then covered in burlap and plaster for protection. [Photos: Oldest Known Horned Dinosaur in North America]

After a 12-hour truck ride, the fossils arrived at the museum. But they were still shrouded in stone. Museum technician Mark Mitchell spent nearly six years revealing the spectacular specimen, and because it was so fragile, "he's put a drop of glue or more on every square millimeter that you see," Henderson said.

Statuesque nodosaur

The 3,000-lb. (1,360 kg) nodosaur is so complete, it looks like a statue whose artist captured every spiky aspect on its body.

"It was very low to the ground, very squat on very short legs," Brown told Live Science. "The entire back, sides, neck and tail were covered in large osteoderms — bony plates that are embedded in the skin."

Normally, osteoderms fall off and become displaced when a dinosaur dies. "In this case, those osteoderms are still preserved in the skin," Brown said. "Not only that, the osteoderms are capped with layers of keratin, the same stuff your fingernails are made of. Normally, it doesn't fossilize."

The herbivore likely ate conifers, cycads (woody plants with seeds) and ferns. "They had very wimpy teeth," Henderson said. "They had a beak like a turtle, and they would just gather the food. [There was] very little chewing." Rather, a system of stomachs would have processed the fibrous food, he said.

"Some people have even suggested that if you were to stand beside them, you would hear all of the rumbling from their guts," Henderson said, referring to nodosaurs. The researchers found a soccer-ball-size mass of fossilized food in the stomach of the specimen that he hopes to analyze soon, Henderson added.

The earliest nodosaurs are known from the Jurassic (a period lasting from 199.6 million to 145.5 million years ago), but most, including the newfound beast, lived during the Cretaceous period (145.5 million to 65.5 million years ago), Brown said.

Nodosaurs have been found on every continent except Antarctica, Henderson said. The new beast is now on display at the museum in an exhibit called "Grounds For Discovery," that highlights fossilized creatures found by industry in Alberta.

Most complete fossil?

Though the nodosaur specimen is in superb condition, it's not the most well-preserved dinosaur on record. That honor likely goes to one of the bird-like dinosaurs with fossilized feathers that farmers and researchers have discovered in China's Liaoning province, Henderson said. [In Photos: Wacky Fossil Animals from Jurassic China]

The nodosaur's tail and hind legs are missing, Henderson said. That's because the mining company swept them away before realizing it had a fossil on its hands.

Instead, the nodosaur is the most well-preserved armored dinosaur on record, a title that still has a lot of swagger, Henderson said.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.