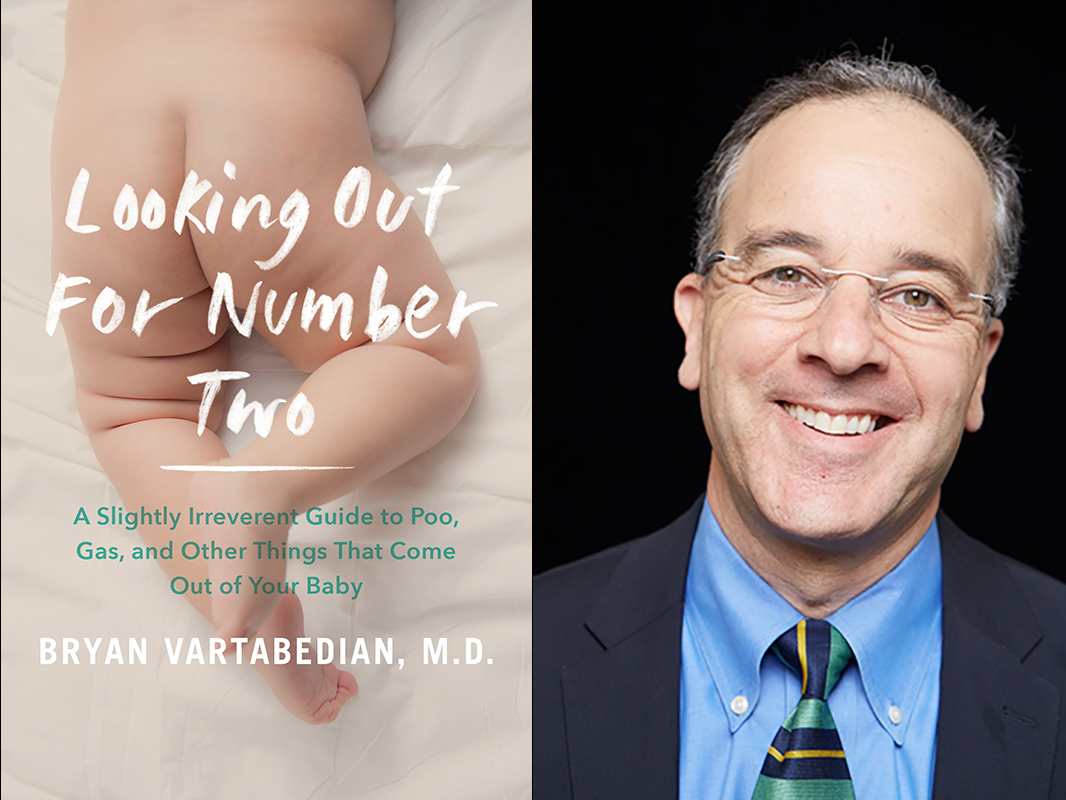

Doctor of Baby Poop: Q&A with Author of 'Looking Out for Number Two'

When Dr. Bryan Vartabedian launched his career as a pediatric gastroenterologist more than 20 years ago, he never imagined that one day he'd be standing in his office contemplating a garbage bag stuffed with two months' worth of soiled diapers, each one carefully marked, catalogued and frozen by a concerned mother who wanted his expert prognosis on her baby's bowel movements.

But that's just another day in the life of a physician who specializes in "the ins and outs" of infant digestion.

Vartabedian's whimsically titled new book "Looking Out for Number Two: A Slightly Irreverent Guide to Poo, Gas, and Other Things That Come Out of Your Baby," released today (May 25) in the U.S. by Harper Wave, draws on his decades of experience treating babies and gazing long and hard at the contents of their diapers, frozen and fresh. It offers a reassuring (and humorous) perspective on the mysterious and sometimes alarming effluvia that infants produce — often from both ends at the same time. [Read an excerpt from "Looking Out for Number Two"]

Much can be learned from a baby's poop in particular, and Vartabedian offers fascinating insights on the coded messages that can be gleaned from stools' smells, shapes and textures, explaining what they can teach us about babies' digestive health.

Baby poop can take many forms that new parents might find inexplicable or even alarming, and Vartabedian addresses them all: from "poo in balls" and the "supernarrow pencil poo" to a variety of "smears, smudges, squirts and leaks" and the dreaded "monster poo of destruction." He outlines what each of these various incarnations reveal about what's happening in a baby's gut — and when they might require a closer look from a pediatrician.

Vartabedian recently spoke with Live Science about "Looking Out for Number Two," delivering a healthy load of easily digestible information that won't be quickly flushed from your memory.

This Q&A has been lightly edited for clarity and content.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Live Science: What moved you to write a book about baby poop?

Dr. Bryan Vartabedian: This is a subject that I deal with on a daily basis, and it is a huge preoccupation for young parents. That led me to pull together all the things that I've seen over the past 20 years, and all the questions I've gotten about baby poo. On top of this is the idea that we're learning more about what's happening in the digestive tract in babies, so I folded a lot of that into the book as well.

Live Science: A baby's earliest hospital records typically include the child's footprints, but in your book, you mention a baby's "poo print." Could you explain what that is and why it's important?

Vartabedian: Babies are effectively born with a sterile intestinal tract, but in the first minutes to hours to days of life they acquire bacteria that will become part of the populations that they'll carry for years to come. Depending on how a baby is born, how they're fed, how they're handled — that will shape the kind of baby biome [an abbreviation for microbiome, or bacterial communities] that they have.

That's what I was getting at, with the "poo print" — everyone's is unique. A baby who's whisked off by hospital personnel will have flora that may be very different than a baby put to the mother's breast immediately or allowed to be handled immediately by the mother. Babies pick up a lot of their bacteria from their environment, particularly from their parents. Very often, babies will have bacteria that can match — or can be very similar to — the "poo print" of their parents. [5 Things Your Poop Says About Your Health]

Live Science: Were there important insights about poop that you discovered as a working gastroenterologist, that you didn't learn in medical school?

Vartabedian: I went to medical school in the late 1980s, when what came out of a person's bottom was just a passing thing — quite literally. Since then, we've learned that there's a lot happening between the bacteria that live in the intestinal tract, and our immune system — about 70 percent of the immune cells in our body live in our gut. Learning to live with bacteria is now recognized as a critical part of early development. The whole concept of the microbiome, how that is associated with disease and wellness — none of that was ever considered important when I was in medical school.

And, of course, there are all the details about why babies poop after they eat, why poop is bright electric-green sometimes — those were all things I learned as part of the practical aspects of working for 20 years in the largest children's hospital in the country.

Live Science: Is there one thing in your book that you wish someone had told you when you were just starting out as a physician?

Vartabedian: That burping is a lot about luck. There's a valve at the top of the stomach that indiscriminately opens and closes to allow air to come out. Pediatric nurses, doctors and baby specialists like to think that there are special techniques to burping, but what it really comes down to is a whole lot of luck. That was one thing I learned as a young father, that burping is more about luck, rather than skill.

Live Science: Have recent medical discoveries or new technologies dramatically changed how doctors understand infant digestion?

Vartabedian: Absolutely. Advances in fiberoptic technology have allowed us to look into the intestinal tracts of babies, that's something that wasn't possible before. Our understanding of infant nutrition has grown as well. It used to be that milk was thought of as something that just made a baby fat and happy. But now we know that the way a baby is fed from the earliest stages of life can have an impact on allergies. We know that babies who are not exposed to cow's milk protein and are exclusively breast-fed have lower instances of Type 1 diabetes. All these things are starting to raise questions about the kinds of proteins and foods that we feed babies, and how that can affect lifelong health.

Live Science: Are there any myths about babies and their poop that your book debunks?

Vartabedian: One myth is that iron in infant formula can cause constipation in babies. This is a common myth, and it comes from mothers who take iron and become constipated. It's dangerous because iron deficiency in babies that occurs early in life can be associated with developmental delays. [7 Baby Myths Debunked]

Another one is that breast-fed babies who have some allergies to protein in the mother's milk should be taken off breast milk — but most babies with milk protein allergy can be successfully breast-fed without going onto hypoallergenic formulas.

Actually, I think it's a myth that parents listen to bad information. My experience has been that parents' health literacy is pretty good. But there is increasingly a lot of misinformation out there, so parents do have to be careful.

Live Science: For many new parents, the biggest challenge can be simply interpreting all these weird and mysterious things that babies do. How might your book help them with that, at least as far as a baby's digestion is concerned?

Vartabedian: This is a core preoccupation of early parenthood: Is my baby normal? Is what I'm seeing representative of a problem? Babies don't do much — they eat, sleep and poop. So, there's a tendency to focus on all of these things. Eating and sleeping have received a lot of attention over the years in many books — this is the first book to address all the ins and outs of babies' digestion. All the details, presented in a way that's entertaining and fun, will help a parent really understand and feel better about what their baby's doing — or not doing.

Live Science: What would be the single most important guideline for new parents to keep in mind when it comes to their baby's poop — other than, "Read this book!"

Vartabedian: You really have to know and understand your baby's cues, because every baby is different.

One of the problems with parenting literature or even parenting books — not mine, of course — is that we try to put kids into boxes, and you really have to understand your baby's signals and patterns. Here's a good example: Mothers that are breast-feeding will usually feed the baby on one breast, then burp the baby, then put the baby on the second breast. There are some personalities in babies where they don't want to be burped. So, the mother who's hell-bent on making that baby burp will struggle with that baby, and the baby will scream because she wants to eat. And all that screaming leads to more swallowed air, which defeats the whole point of burping. That's a situation where you have to understand cues from your baby, and be able to flow with things in a way that's natural.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.