Huge cyclones rage near Jupiter's mysterious poles, and the giant planet's powerful auroras are fundamentally different from Earth's northern and southern lights.

Those are just two of the discoveries made by NASA's Juno spacecraft during its first few close passes over Jupiter's poles, mission scientists report in two studies published online today (May 25) in the journal Science.

"What we've learned so far is Earth-shattering. Or should I say, Jupiter-shattering," Juno principal investigator Scott Bolton, of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, said in a statement. [Photos: NASA's Juno Mission to Jupiter]

"Discoveries about its core, composition, magnetosphere, and poles are as stunning as the photographs the mission is generating," added Bolton, the lead author of one of the new Science studies and a co-author of the other.

Lifting the veil on Jupiter

The $1.1 billion Juno mission launched in August 2011 and arrived in orbit around Jupiter on July 4, 2016. Since then, the solar-powered spacecraft has been using eight instruments to study the gas giant's composition, interior structure, and gravitational and magnetic fields. It will continue to do this work, barring some sort of malfunction, through at least February 2018, the end of Juno's primary mission.

The mission's name is a nod to the Roman goddess Juno, who was able to look through the clouds to see her frequently misbehaving husband Jupiter, the king of the gods, who was hiding within. Likewise, the Juno probe is peering beneath Jupiter's thick clouds to learn about the planet's formation and evolution — information that could shed light on the history of our solar system as a whole, NASA officials have said.

Juno makes most of the measurements relevant to this goal during its close flybys, which occur once every 53.5 days and bring the probe within about 3,100 miles (5,000 kilometers) of Jupiter's poles. (The original mission blueprint called for Juno to maneuver to a less elliptical orbit and make these flybys every 14 days, but an issue with two helium valves in the spacecraft's propulsion system nixed that plan.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

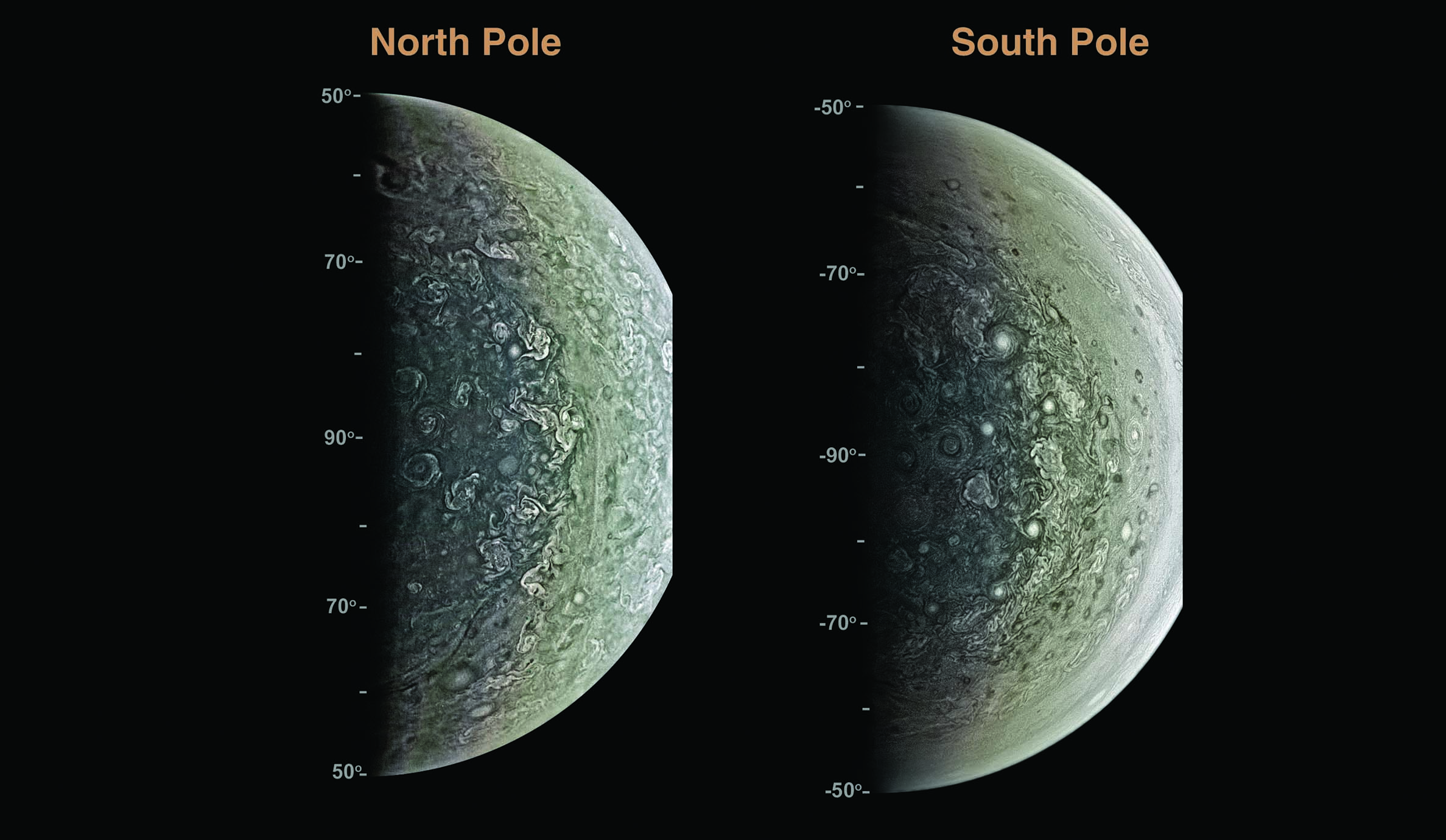

Before Juno, no spacecraft had ever gotten close-up looks at Jupiter's poles. These mysterious regions are beautiful and bizarre, the Bolton-led study reports.Juno has now made five of these data-collecting "perijove passes." The first came on Aug. 27, 2016, and the most recent occurred just last week, on May 19. The two new Science papers report results just from the first few flybys, as well as some measurements Juno made as it neared Jupiter in June 2016.

"When you look over the poles, all of those zones and belts are gone," Bolton said in a Science podcast that was also released today, referring to the striped cloud patterns prevalent at Jupiter's lower latitudes. "You see this bluish hue to it, and there's tons of these cyclone and anticyclonic storms spinning around the poles. It almost looks like meteor craters, but, of course, it's all atmosphere. It's all gas." [Photos: Jupiter, the Solar System's Largest Planet]

It's unclear what, exactly, drives these polar cyclones, some of which are up to 870 miles (1,400 km) wide, or if they're stable over long periods, Bolton said.

"Over the course of the mission, we'll be able to watch the poles and see how they evolve," he said in the podcast. "Maybe these cyclones are always there, but maybe they just come and go."

Juno also has been mapping out the concentration of water and ammonia deep within Jupiter's atmosphere. Data gathered during the first few passes has revealed that ammonia abundances vary quite a bit from place to place — a discovery that surprised the mission team.

"Most scientists have felt that, as soon as you go down a little bit into Jupiter, everything would be well-mixed, and we're finding that that's just not true at all," Bolton said. "There's structure down deep, but it doesn't seem to match the zones and belts. And so we're still trying to figure it out."

Juno's measurements during the first few close passes also show that Jupiter's magnetic field is nearly two times stronger than scientists had predicted. And the probe's gravity data suggest that "there's a lot of strange, deep motions that possibly are going on inside of Jupiter," Bolton said.

"What Juno's results are showing us is that our ideas of giant planets maybe are a little bit oversimplified," he added. "They're more complex than we thought; the motions that are going on inside are more complicated. It's possible that they formed differently than [suggested by] our simple ideas."

Otherworldly auroras

Earth's auroras result when the solar wind — charged particles streaming from the sun — slam into the planet's atmosphere, generating a glow. (Earth's magnetic field funnels these particles toward the poles, which explains the phenomenon's other name: the northern and southern lights.)

Scientists already knew that the solar wind is a major driver of Jovian auroras, and that the planet's rotation is involved as well. But Juno has given researchers a chance to study the phenomenon in unprecedented detail; no other spacecraft had ever flown close to the planet's auroral regions before, Bolton said.

The second newly published Science study, which was led by John Connerney of the Space Research Corporation and NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, details what the Juno team learned about the auroras and Jupiter's magnetosphere from the initial perijove passes. Once again, there were some surprises.

For example, the particles associated with Jupiter's auroras seem to be different than the ones responsible for Earth's most stunning light shows, study team members said.

"We can see that it doesn't work exactly like we expected, or as the Earth does," Bolton said. "We haven’t been able to see particles necessarily going up and down in both directions like we would've expected to cause the aurora. So there's definitely some strange phenomena that we still need to comb through and understand better."

Further close flybys should allow the Juno team to investigate such questions, he added.

"We're at the beginning of the mission, so these first results are sort of telling us some of our models and ideas are wrong and need to be corrected," Bolton said. "And we have some ideas of which way to go, but it really takes some more data to really test whatever theories we put together and see if we're right."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.