Can a Drug That Fights Parasites Also Help with Autism?

A 101-year-old drug that is often used to treat people in Africa with parasitic infections may help ease some of the symptoms of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in children, a new study finds.

However, researchers are urging caution about the preliminary results of the drug, called suramin. The study was extremely small and involved only boys, who were given just one dose of the drug.

The study was well designed, but the findings don't necessarily suggest that suramin works to treat autism, said Dr. Jay Gargus, a director of the Center for Autism Research and Translation at the University of California, Irvine, who was not involved in the study. [Beyond Vaccines: 5 Things That Might Really Cause Autism]

"I don't think the suramin is the important part of the paper," Gargus said. "The important part of the paper is how [the author] goes through carefully describing what kinds of measures he's going to do, how he's going to do this, how he's going to work his way through understanding what these drugs do."

Still, the initial results are encouraging, said study lead researcher, Dr. Robert Naviaux, a professor of genetics and co-director of the Mitochondrial and Metabolic Disease Center at the University of California, San Diego. "A single treatment with low-dose suramin was safe and produced significant improvements in the core symptoms and metabolism associated with ASD," Naviaux said in a statement.

Suramin study

The study included 10 boys with ASD, ages 5 to 14. Five of the boys received a single, low-dose infusion of suramin, and five received a placebo. The study was double-blinded, meaning that neither the participants nor the researchers knew which of the participants received the drug, and which received the placebo.

After the treatment, the boys in the suramin group showed improvements in their social communication, speech and language. They acted calmer and were more focused, showing fewer repetitive behaviors and less need to use their coping skills, the researchers said. These differences were documented with observational techniques, interviews and questionnaires.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Reports from the boys' parents suggested that the five boys who received suramin improved for three weeks, then gradually decreased toward their original baseline over the next three weeks, the researchers said in the study.

"We had four nonverbal children in the study," Naviaux said, adding that the two who received suramin said the first sentences of their lives about one week after the treatment. This did not happen in the two nonverbal kids given the placebo, Naviaux said.

Moreover, the boys who received suramin made more progress during their speech therapy and occupational therapy programs than the boys given the placebo, Naviaux said.

How suramin works

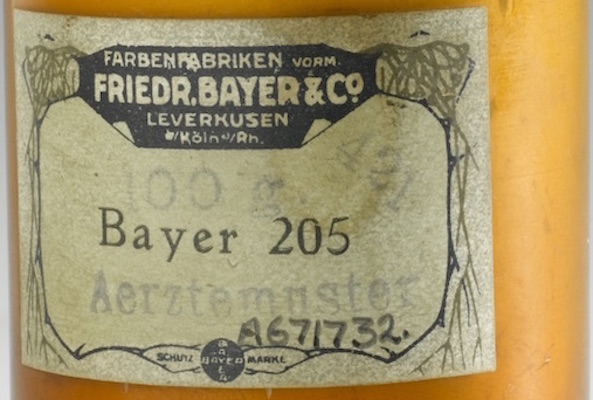

The German dye manufacturers, Frederich Bayer and Co., developed suramin in 1916, initially calling it Bayer 205. The drug proved to be effective against parasites that cause African sleeping sickness.

Suramin works by stopping certain molecules from binding to proteins called "purinergic receptors," which are found on every cell in the body. Naviaux's idea is that cells that are stressed release certain molecules, and that these molecules then bind to purinergic receptors and impair cell function.

Although it's unclear what causes autism, the condition might be driven, in part, by impaired communication between cells in the brain, gut and immune system, he said. Other causes likely include genetic and environmental factors, he said.

In people with autism, suramin may stop the molecules from binding to purinergic receptors, and let the cells function more normally, Naviaux said. [10 Things You Didn't Know About the Brain]

Earlier studies in mice with autism traits showed that the drug alleviated some symptoms of the condition. For example, in 6-week-old mice with traits of autism, suramin improved social behavior, metabolism and motor coordination, according to a 2013 study published in the journal PLOS ONE.

In another study, published in 2014 in the journal Translational Psychiatry, adult mice that received suramin showed improved social behaviors and metabolism, but no motor skill improvement.

Reactions and concerns

Other researchers call Naviaux's ideas about the role of purinergic receptors in autism an "emerging hypothesis," but say it's a "creative way of thinking about" the molecular processes behind autism, Gargus said.

Gargus noted several limitations in the study. For instance, all five boys in the suramin group developed a temporary rash, but none in the placebo group did. It's possible that parents in the suramin group noticed this and realized that their child had received the drug, inadvertently "un-blinding" the study, Gargus said. The researchers mentioned this as a possible limitation in the study, too.

What's more, the boys in the placebo group showed very little improvement — an anomaly in neurobehavioral testing, because usually the placebo effect is strong, and the group given the placebo shows some kind of improvement, Gargus said.

Gargus added that given the number of tests in the study, it's not surprising the autism group scored better than the placebo group on some of the measures. "If you give enough scales, one of them is probably going wind up showing you a significant effect," Gargus told Live Science. [Typical Toddler Behavior, or ADHD? 10 Ways to Tell]

Suramin is not approved to treat ASD by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and the drug is not commercially available. Naviaux has filed a patent application related to antipurinergic therapy for ASD and related disorders, and two of the study's authors have connections to pharmaceutical companies.

The study was published online May 26 in the journal Annals of Clinical and Translational Neurology.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.