Photos: Lionfish Invade the 'Twilight Zone'

Lion of the Sea

A lionfish (Pterois volitans) cruises near Fiji in this 2008 image. These Indo-Pacific natives have established themselves in the western Atlantic off the U.S. coast and in the Caribbean, probably after unwanted aquarium specimens were released into the ocean. Now, lionfish are threatening local fish species, including ones that science has yet to discover. [Read the full story on the lionfish invasion]

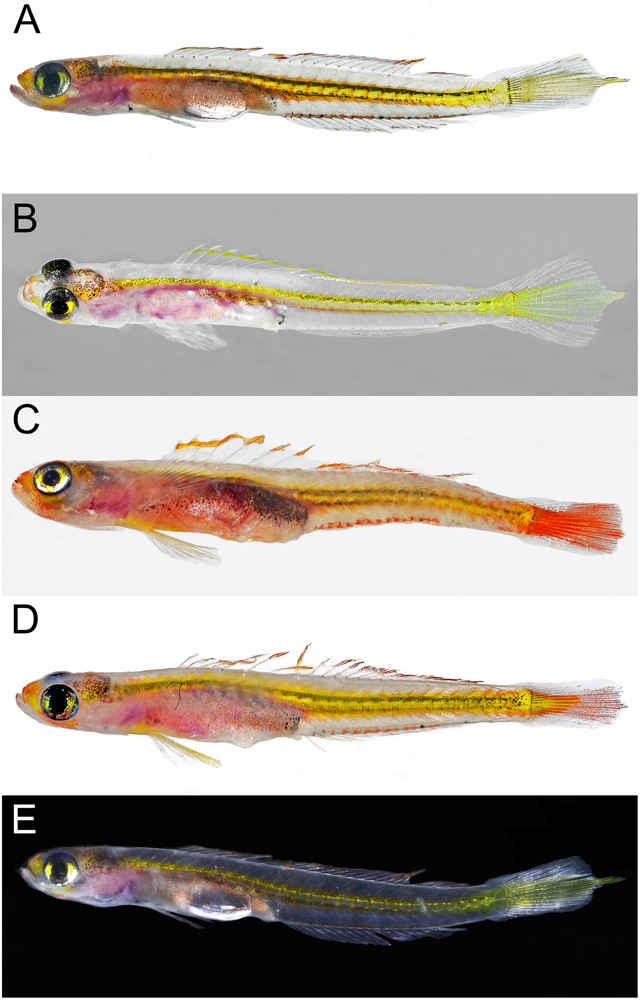

Ember goby

The newly discovered Ember goby (Palatogobius indendius) is an example of a fish that was found to be lionfish food before it even had a proper scientific identification. In February 2015, researchers using the Curasub submersible observed a lionfish stalking a school of Ember gobies in a deep reef 384 feet (117 meters) below the ocean surface.

One fish, two fish

Ember gobies have now been observed swimming as deep as 650 feet (200 meters) near Curacao, Dominica and Honduras. They don't seem at risk from extinction due to lionfish hunting, but researchers are alarmed to find that lionfish are hunting small fish at these depths. Many deep reef species are unknown, especially species with smaller populations that the Ember goby.

Curasub

Luke Tornabene, the curator of fishes at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle and a professor of aquatic and fishery sciences at the University of Washington, climbs aboard Curasub, a manned submersible capable of deep-reef dives.

Readying to dive

Curasub floats in the Carribean as researchers ready for a deep-reef dive. The sub allows scientists to capture deep-reef fish by stunning them with an anesthetic and then vacuuming them up with a hose attachment. But lionfish are tricky. They don't respond to the anesthetic and are best caught by spearfishing divers — who unfortunately cannot dive to the depths of deep reef ecosystems.

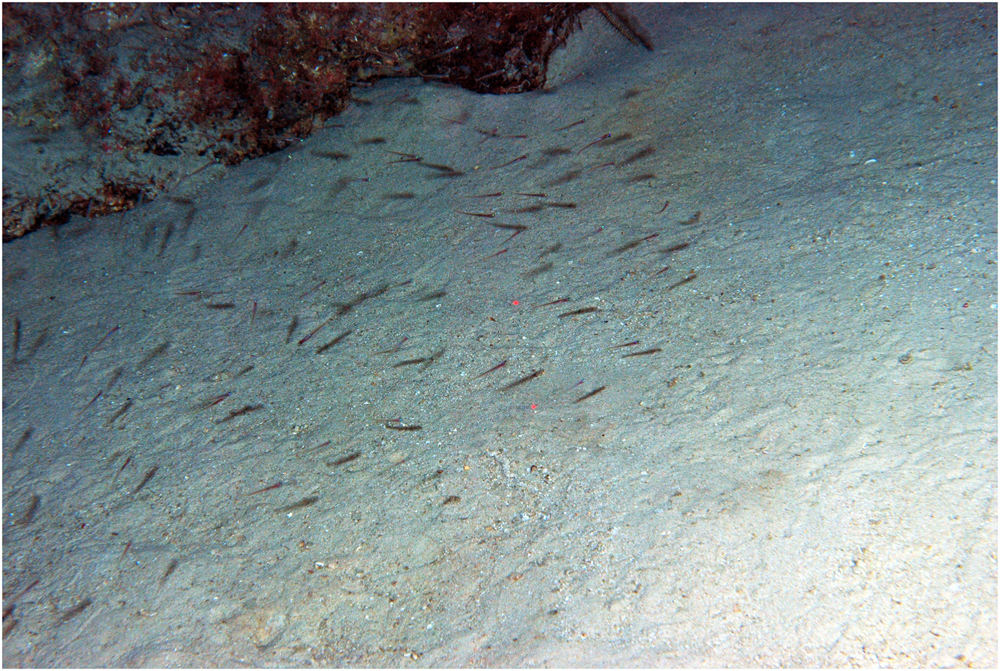

Schooling gobies

A school of ember gobies near Curacao. These fish grown less than an inch (22 millimeters) long, so they're ripe prey for lionfish both as juveniles and as adults. They tend to hover near the seafloor or along rock walls, making them easy to herd into a corner for the slow-cruising lionfish predators.

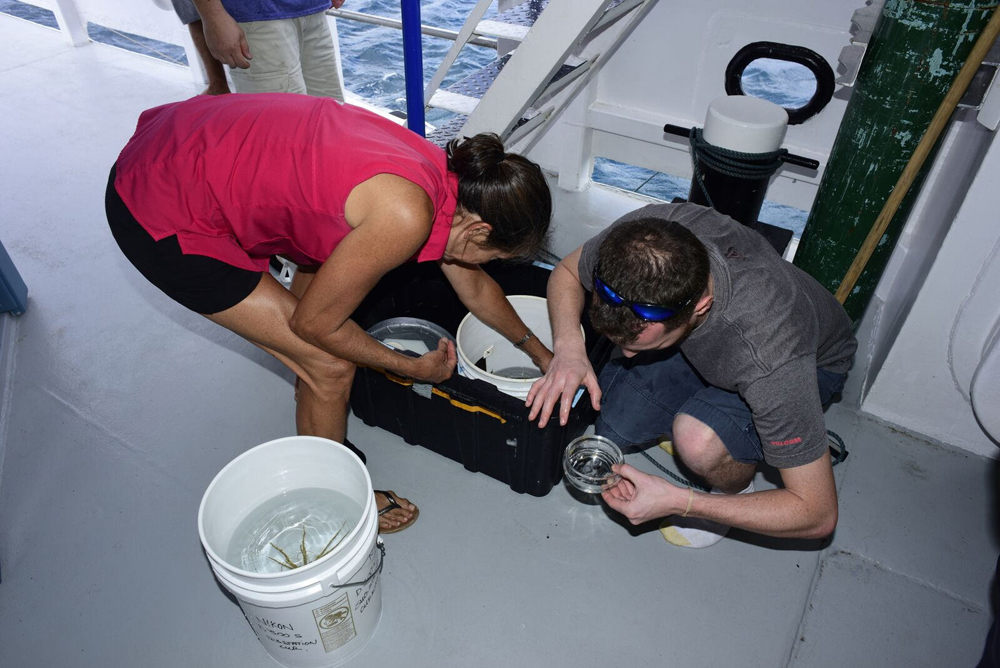

Sorting Fish

Researchers sort through the catch from a submersible dive. Many species of deep-reef fish have yet to be discovered, and scientists are concerned that invasive lionfish could severely impact the populations of some species before the fish can even be quantified.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Venomous fish

An invasive lionfish off the coast of the southeastern United States in 2004. Lionfish have been found plying deep waters, as far down as 300 feet (91 meters) near Florida. The fish are voracious hunters, and their spines are venomous. Hunting by humans may help keep the lionfish population in check in at least some vulnerable reefs, according to a 2014 study.

Lionfish and grunt

This 2004 NOAA image shows a lionfish swimming near a white grunt (Haemulon plumieri), a native of the western Atlantic. According to NOAA, four national marine sanctuaries have been invaded by lionfish: the Florida Keys, Gray's Reef off of Georgia, Flower Garden Banks near Galveston, Texas, and Monitor Marine Sanctuary off North Carolina's Outer Banks.

Big fish, small fish

A big and small lionfish swim side-by-side off the continental slope of the southeastern United States in 2004. Lionfish can rapidly colonize new areas thanks to their speedy reproductive rate. According to a 2012 master's dissertation from the University of Florida, lionfish spawn year-round and an adult female can potentially release 2.3 million eggs over her lifetime. [Read the full story on the lionfish invasion]

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.