'Twilight Zone' Horror Story: Lionfish Prey on Unknown Fish Species

Invasive lionfish in the Caribbean Sea are scarfing down fish species that scientists haven't even discovered yet.

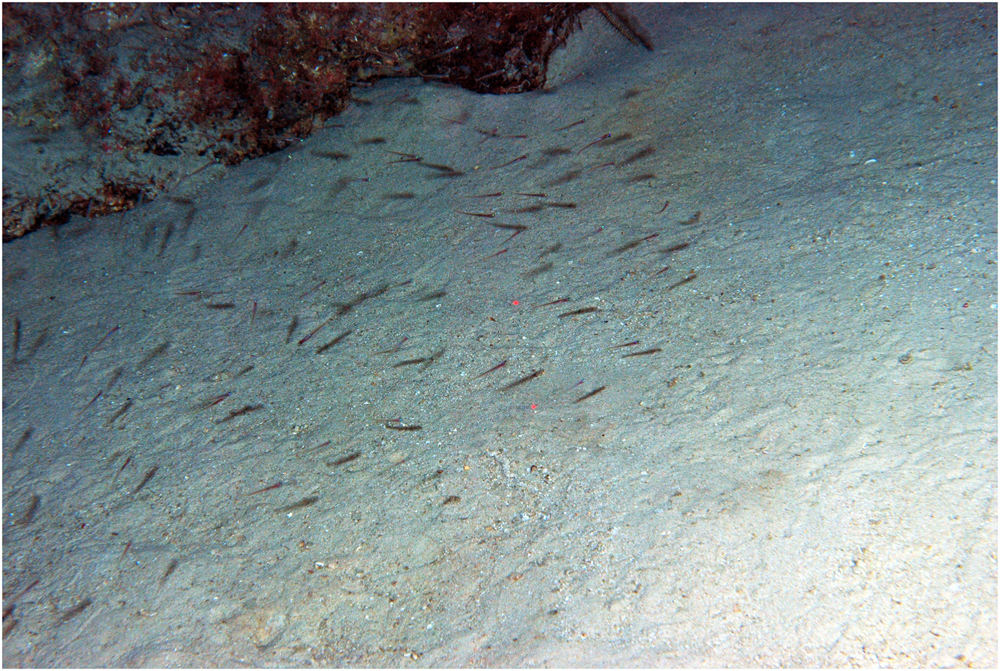

New research published May 25 in the journal PLOS ONE reveals video of a lionfish hunting a new species of yellow-and-orange goby off the coast of Curaçao. The gobies, dubbed Palatogobius incendius, or ember gobies, are a mere 0.8 inches (22 millimeters) long and hover just above the seafloor in deep reef areas. In the video, captured by the submersible Curasub in February 2015, a lionfish glides over a school of gobies, herding them against a rock wall and striking twice.

"Once we discovered invasive lionfish — sometimes in huge numbers — inhabiting barely explored deep reefs, our concern was that these voracious predators might be gobbling up biodiversity before scientists even know it exists," study co-author Carole Baldwin, the curator of fishes at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., said in a statement. "This study suggests that they are doing just that." [Gallery: The Invasive Lionfish and its New Prey]

Introduced fish

Lionfish (Pterois volitans and P. miles) originally hail from the Indo-Pacific, but arrived in the western Atlantic in the 1980s or 1990s. No one knows exactly how the fish invaded Atlantic waters, but home aquarists who dump unwanted lionfish into the ocean may have been the cause, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

On Feb. 9, 2015, the submersible Curasub launched from Substation Curaçao and captured video of a school of about 50 orange-striped gobies hanging out near a rock wall 384 feet (117 m) down. In the video, a lionfish slowly cruises over the school with its fins spread wide, striking at the school with a sudden surge. The gobies fled to join a second, nearby school of the same species, but it was no use. About a minute after the first strike, the lionfish cornered the larger school against the rock wall and struck again, seeming to swallow some fish.

Predator impacts

P. incendius has now been collected or at least observed in deep reefs near Curaçao, Cominica and Honduras, the researchers reported. It does not seem to be in immediate danger of extinction, despite the lurking threat of the lionfish. But just the fact that lionfish are apparently hunting small fish in deep reefs has scientists alarmed.

"The other species still undescribed on these reefs are very rare and occur in lower abundances than our new species. If they are getting eaten by lionfish, they may be in more trouble than the ember goby," study co-author Luke Tornabene, the curator of fishes at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle, said in a statement.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers hope to investigate even deeper into the reef ecosystem. This summer, they will take a different submersible up to 2,700 feet (800 m) down near Honduras. Unfortunately, lionfish are difficult to capture using submersibles, because they don't respond to the anesthetic that the researchers use to temporarily stun fish so they can scoop them from the water. Divers with spears are the most reliable way to catch lionfish, the researchers wrote, but they can swim down to only about 490 feet (150 m). The team is now experimenting with lionfish traps to try to capture the invasive fish and investigate their gut contents from deep reefs.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.