This Mask Is Among the Oldest Human-Made Metal Objects in South America

An ancient, rectangular copper mask recently found in the southern Andes in Argentina is about 3,000 years old — one of the oldest human-made metal object from South America — and its discovery challenges the accepted idea that South American metalworking originated in Peru, according to archaeologists.

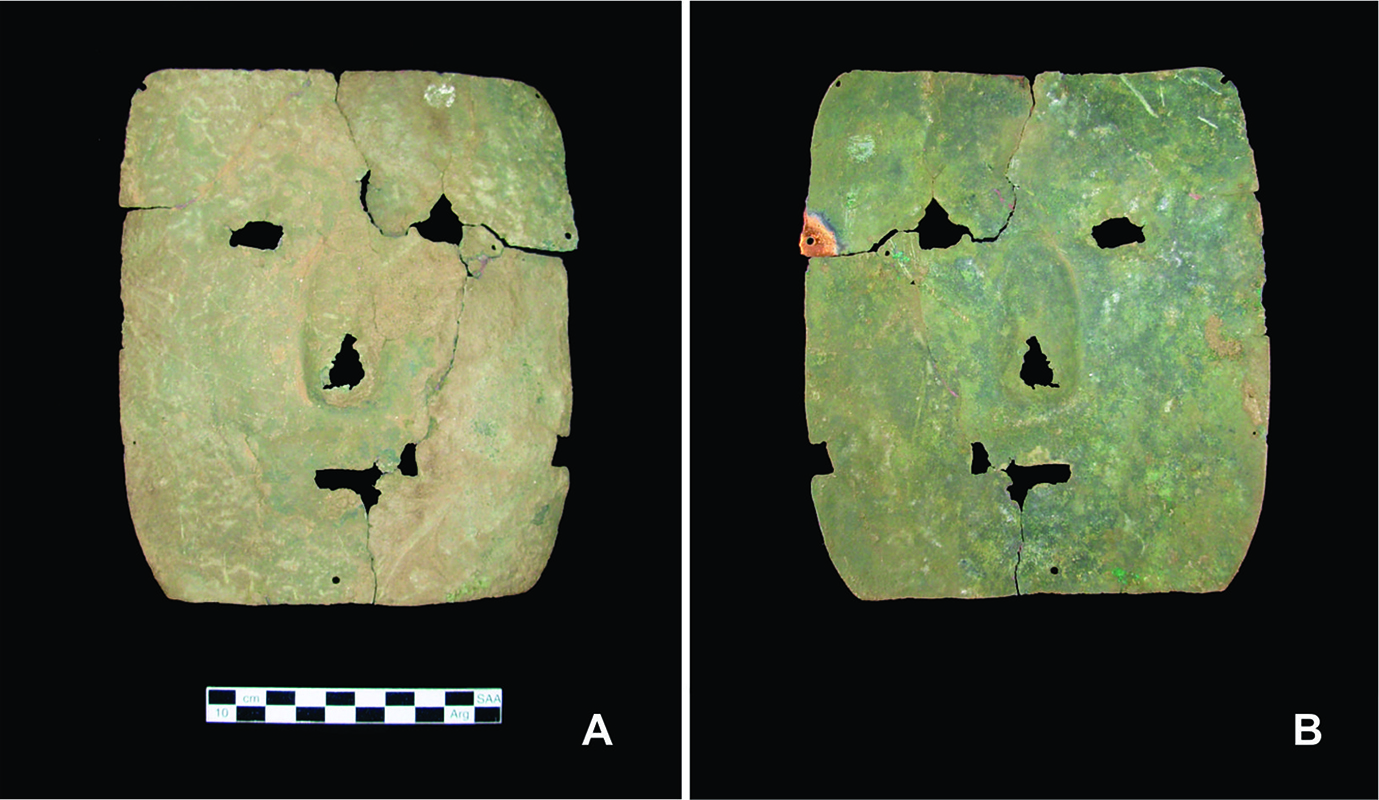

Found at a site where adults and children were buried, the mask dates to approximately 1000 B.C., the scientists wrote in a study describing the find. Holes mark the position of the mask's eyes, nose and mouth, with additional small, circular openings near the edges that could have been threaded to secure it to a face or an object.

Sources of copper ore have been found within 44 miles (70 kilometers) of the location where the mask was uncovered, suggesting that it was produced locally. It is therefore highly probably that metalworking emerged in Argentina at the same time that it was developing in Peru, the researchers wrote in the study. [Photos: Journey into the Tropical Andes]

Gold objects estimated to be nearly 4,000 years old have been found in southern Peru, according to a study published in February 2008 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Bronze artifacts dating to about A.D. 1000 were previously found in the Peruvian Andes, though it is difficult for experts to say for sure if the objects originated where they were found, or if trade brought them there, Live Science reported in 2007. But evidence of local metalworking in Peru still lingers — in trace metals found in local sediments, dating to pre-Incan times, scientists also learned in 2007.

Weather during the summer rainy season exposed the metal mask — along with a collection of human bones — in a tomb near the village of La Quebrada, in northwestern Argentina, the study authors wrote. There were about 14 bodies in the burial area, with the bones all mixed together and the mask placed on top of one corner of the pile.

Nearby, a second burial area held a single occupant. The bones of a child approximately 8 to 12 years old, also dating to about 3,000 years ago, were buried with a stone bead and with what appeared to be a copper pendant, perforated by a small hole near the top.

The mask measures about 7 inches (18 centimeters) long and nearly 6 inches (15 cm) wide. Impurities in the copper are lower than 1 percent. To create the mask, someone would have hammered the metal flat while it was cold and then reheated it, according to the researchers.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The age of these metal objects — particularly the mask, crafted to deliberately resemble a human face — strongly suggests that people in the Argentinian regions of the Andes were shaping copper into artifacts earlier than previously thought, the study authors noted.

"Proof of copper smelting and annealing [a process of cooling metal slowly to make it stronger] further highlights the northwest Argentinian valleys and northern Chile as early centers in the production of copper," the researchers wrote.

"This data is essential to any narrative that seeks to understand the emergence of Andean metallurgy," they added.

The findings, which were published online June 5 in the journal Antiquity, were originally published in 2010 in the journal Boletín del Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine. Her book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control" will be published in spring 2025 by Johns Hopkins University Press.